User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/LimitingMasses

Mass Upper Limits

|

|---|

| | Tiled Menu | Tables of Content | Banner Video | Tohline Home Page | |

Spherically symmetric, self-gravitating, equilibrium configurations can be constructed from gases exhibiting a wide variety of degrees of compressibility. When examining how the internal structure of such configurations varies with compressibility, or when examining the relative stability of such structures, it can be instructive to construct models using a polytropic equation of state because the degree of compressibility can be adjusted by simply changing the value of the polytropic index, <math>~n</math>, across the range, <math>0 \le n \le \infty</math>. (Alternatively, one can vary the effective adiabatic exponent of the gas, <math>\gamma_g = 1 + 1/n</math>.) In particular, <math>n = 0</math> (<math>\gamma_g = \infty</math>) represents a hard equation of state and describes an incompressible configuration, while <math>n = \infty</math> (<math>\gamma_g = 1</math>) represents an isothermal and extremely soft equation of state.

Isolated Polytropes

Isolated polytropic spheres exhibit three attributes that are especially key in the context of our present discussion:

- The equilibrium structure is dynamically stable if <math>n < 3</math>.

- The equilibrium structure has a finite radius if <math>n < 5</math>.

- The equilibrium structure can be described in terms of closed-form analytic expressions for <math>n = 0</math>, <math>n = 1</math>, and <math>n = 5</math>.

Isothermal Spheres

Isothermal spheres (polytropes with index <math>n=\infty</math>) are discussed in a wide variety of astrophysical contexts because it is not uncommon for physical conditions to conspire to create an extended volume throughout which a configuration exhibits uniform temperature. But mathematical models of isothermal spheres are relatively cumbersome to analyze because they extend to infinity, they are dynamically unstable, and they are not describable in terms of analytic functions. In such astrophysical contexts, we have sometimes found it advantageous to employ an <math>n=5</math> polytrope instead of an isothermal sphere. An isolated <math>n=5</math> polytrope can serve as an effective surrogate for an isothermal sphere because it is infinite in extent and is dynamically unstable, but it is less cumbersome to analyze because its structure can be described by closed-form analytic expressions.

Bounded Isothermal Sphere & Bonnor-Ebert Mass

In the mid-1950s, Ebert (1955) and Bonnor (1956) independently realized that an isothermal gas cloud can be stabilized by embedding it in a hot, tenuous external medium. The relevant mathematical model is constructed by chopping off the isothermal sphere at some finite radius — call it, <math>\xi_e</math> — and imposing an externally applied pressure, <math>P_e</math>, that is equal to the pressure of the isothermal gas at the specified edge of the truncated sphere. But for a given mass and temperature, there is a value of <math>P_e</math> below which the truncated isothermal sphere is dynamically unstable, like its isolated and untruncated counterpart. Viewed another way, given the value of <math>P_e</math> and the isothermal sound speed, <math>c_s</math>, a bounded isothermal sphere will be dynamically stable only if its mass is below a critical value,

|

Bonnor-Ebert Mass

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

where <math>\alpha</math> is a dimensionless coefficient of order unity. This limiting mass is often referred to as the Bonnor-Ebert mass. It appears most frequently in the astrophysics literature in discussions of star formation because that is the arena in which both Bonnor and Ebert were conducting research when they made their discoveries.

As is reviewed in a related discussion and as is documented in the table accompanying the expression for <math>M_\mathrm{max}</math>, above, Bonnor (1956) used Emden's (1907) tabulated properties of a detailed force-balance, isothermal sphere to determine that the dimensionless radius of this limiting configuration is <math>\xi_e \approx 6.5</math> and that the leading coefficient, <math>\alpha \approx 1.18</math>. It is worth noting that a virial energy analysis of bounded isothermal spheres produces the same expression for <math>M_\mathrm{max}</math> but a somewhat different value for <math>\alpha</math>. In this simpler virial analysis, however, the value of the leading coefficient has an analytic prescription, namely, <math>\alpha = (3^4 \cdot 5^3/2^{10}\pi)^{1/2} \approx 1.77408</math>.

Our detailed force-balance analysis of truncated and pressure-bounded, <math>n=5</math> polytropes identifies a physically analogous limiting mass. If the average isothermal sound speed, <math>\bar{c_s}</math>, as defined elsewhere, is used in place of <math>c_s</math>, the mathematical expression for <math>M_\mathrm{max}</math> has exactly the same form as in the isothermal case. But for the <math>n=5</math> polytrope we know that the limiting configuration has a dimensionless radius given precisely by <math>\xi_e = 3</math>; and, as a result, the leading coefficient in the definition of <math>M_\mathrm{max}</math> is prescribable analytically, namely, <math>\alpha = 2^{-3/10} \cdot (3^7/2^8 \pi)^{1/2} \approx 1.33943</math>. As is documented in the table accompanying the relation for <math>M_\mathrm{max}</math>, above, in the case of a truncated <math>n=5</math> polytrope, a simpler virial energy analysis gives, <math>\alpha = (3^{20}/2^{12}\cdot 5^7\pi)^{1/2} \approx 1.86236</math>.

Schönberg-Chandrasekhar Mass

In the early 1940s, Schönberg & Chandrasekhar (1942) discovered that a star with an isothermal core will become unstable if the fractional mass of the core is above some limiting value. They discovered this by constructing models that are now commonly referred to as bipolytropes, that is, models in which the star's core is describe

Work in Progress

Virial Equilibrium

By examining the virial equilibrium of nonrotating, spherically symmetric configurations that are embedded in an external medium of pressure <math>P_e</math>, one can begin to appreciate that there is a mass above which no equilibrium exists if the effective adiabatic exponent of the gas is <math>\gamma_g < 4/3</math>. Assuming uniform density and uniform specific entropy configurations for simplicity, there is an analytic expression for this limiting mass and for the equilibrium radius of that limiting configuration. Specifically,

<math> M_\mathrm{max}^2 = \frac{3\cdot 5}{2^2 \pi} \biggl(\frac{4}{3\gamma_g} - 1 \biggr) \biggl[ \frac{3 \gamma_g}{4} \biggr] ^{4/(4-3\gamma_g)} \biggl[ \frac{\bar{c_s}^8}{G^3 P_e} \biggr] \, , </math>

and,

<math> R_\mathrm{eq}^2 = \frac{1}{5^2} \biggl[ \frac{4}{3\gamma_g} \biggr]^{2/(4-3\gamma_g)} \biggl[ \frac{GM_\mathrm{max}}{\bar{c_s}^2 } \biggr]^2 = \frac{3}{2^2 \cdot 5\pi} \biggl[ \frac{3\gamma_g}{4} \biggr]^{2/(4-3\gamma_g)} \biggl( \frac{4}{3\gamma_g} - 1 \biggr) \biggl[ \frac{\bar{c_s}^4 }{GP_e} \biggr] \, . </math>

Polytropes Embedded in an External Medium

Polytropes embedded in an external medium

Summary of Analytic Results

| Example: Specify <math>c_s</math>, <math>P_e</math> and <math>n</math> (or <math>\eta = 1+1/n)</math> | |||||||

|

<math>~n</math> |

<math>\eta</math> |

<math>M_\mathrm{max}</math> |

<math>R_\mathrm{eq}</math> |

||||

|

<math>\alpha_\mathrm{virial}</math> |

<math>\alpha_\mathrm{DHB}</math> |

<math>\mathrm{scale}</math> |

<math>\alpha_\mathrm{virial}</math> |

<math>\alpha_\mathrm{DHB}</math> |

<math>\mathrm{scale}</math> |

||

|

<math>\infty</math> |

1 |

<math>\biggr(\frac{3^4 \cdot 5^3}{2^{10} \pi}\biggr)^{1/2} </math> |

-- |

<math>\biggl[ \frac{c_s^8}{G^3 P_e}\biggr]^{1/2}</math> |

<math>\biggl(\frac{3^2 \cdot 5}{2^6\pi} \bigg)^{1/2}</math> |

-- |

<math>\biggl( \frac{c_s^4}{GP_e} \biggr)^{1/2}</math> |

|

5 |

6/5 |

<math>\biggl( \frac{3^{19}}{2^{12}\cdot 5^9 \pi} \biggr)^{1/2} </math> |

<math>\biggl( \frac{1}{2} \biggr)^{3/10} \biggl( \frac{3^7}{2^8 \pi} \biggr)^{1/2} </math> |

<math>\biggl[ \frac{\bar{c_s}^8}{G^3 P_e}\biggr]^{1/2}</math> |

<math>\frac{3^{9}}{2^{7}\cdot 5^{6} \pi} </math> |

-- |

<math>\biggl( \frac{\bar{c_s}^4}{GP_e} \biggr)^{1/2}</math> |

Bonnor-Ebert Limiting Mass

Here we will refer to the original works of Ebert (1955, ZA, 37, 217) and Bonnor (1956, MNRAS, 116, 351) .

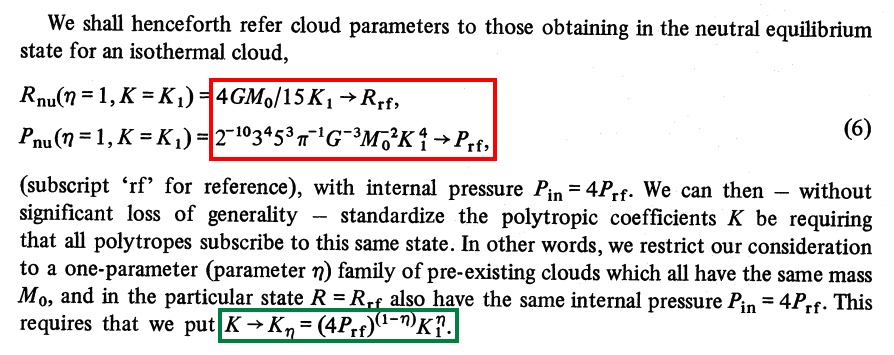

In his study of the "global gravitational stability [of] one-dimensional polytropes," Whitworth (1981, MNRAS, 195, 967) normalizes (or "references") various derived mathematical expressions for configuration radii, <math>R</math>, and for the pressure exerted by an external bounding medium, <math>P_\mathrm{ex}</math>, to quantities he refers to as, respectively, <math>R_\mathrm{rf}</math> and <math>P_\mathrm{rf}</math>. The paragraph from his paper in which these two reference quantities are defined is shown here:

In order to map Whitworth's terminology to ours, we note, first, that he uses <math>M_0</math> to represent the spherical configuration's total mass, which we refer to simply as <math>M</math>; and his parameter <math>\eta</math> is related to our <math>~n</math> via the relation,

<math>\eta = 1 + \frac{1}{n} \, .</math>

Hence, Whitworth writes the polytropic equation of state as,

<math>P = K_\eta \rho^\eta \, ,</math>

whereas, using our standard notation, this same key relation is written as,

<math>~P = K_\mathrm{n} \rho^{1+1/n}</math> ;

and his parameter <math>K_\eta</math> is identical to our <math>~K_\mathrm{n}</math>.

According to the second (bottom) expression identified by the red outlined box drawn above,

<math> P_\mathrm{rf} = \frac{3^4 5^3}{2^{10} \pi} \biggl( \frac{K_1^4}{G^3 M^2} \biggr) \, , </math>

and inverting the expression inside the green outlined box gives,

<math> K_1 = \biggl[ K_n (4 P_\mathrm{rf})^{\eta - 1} \biggr]^{1/\eta} \, . </math>

Hence,

<math> P_\mathrm{rf} = \frac{3^4 5^3}{2^{10} \pi} \biggl( \frac{1}{G^3 M^2} \biggr)\biggl[ K_n (4 P_\mathrm{rf})^{\eta - 1} \biggr]^{4/\eta} \, , </math>

or, gathering all factors of <math>P_\mathrm{rf}</math> to the left-hand side,

<math> P_\mathrm{rf}^{(4-3\eta)} = 2^{-2(4+\eta)} \biggl( \frac{3^4 5^3}{\pi} \biggr)^\eta \biggl[ \frac{K_n^4}{G^{3\eta} M^{2\eta}} \biggr] \, . </math>

Analogously, according to the first (top) expression identified inside the red outlined box,

<math> R_\mathrm{rf} = \frac{2^2 GM}{3\cdot 5 K_1} = 2^{2/\eta} \biggl( \frac{GM}{3\cdot 5}\biggr) K_n^{-1/\eta} P_\mathrm{rf}^{(1-\eta)/\eta} ~~~~\Rightarrow~~~~ R_\mathrm{rf}^\eta = \frac{2^{2}}{K_n} \biggl( \frac{GM}{3\cdot 5}\biggr)^\eta P_\mathrm{rf}^{(1-\eta)} \, . </math>

Related Wikipedia Discussions

|

|---|

|

© 2014 - 2021 by Joel E. Tohline |