User:Tohline/2DStructure/ToroidalCoordinates

Using Toroidal Coordinates to Determine the Gravitational Potential

The detailed derivations and associated scratch-work that support the summary discussion of this chapter can be found under the Appendix/Ramblings category of this H_Book.

|

|---|

| | Tiled Menu | Tables of Content | Banner Video | Tohline Home Page | |

Preamble

As I have studied the structure and analyzed the stability of (both self-gravitating and non-self-gravitating) toroidal configurations over the years, I have often wondered whether it might be useful to examine such systems mathematically using a toroidal — or at least a toroidal-like — coordinate system. Is it possible, for example, to build an equilibrium torus for which the density distribution is one-dimensional as viewed from a well-chosen toroidal-like system of coordinates?

I should begin by clarifying my terminology. In volume II (p. 666) of their treatise on Methods of Theoretical Physics, Morse & Feshbach (1953; hereafter MF53) define an orthogonal toroidal coordinate system in which the Laplacian is separable.1 (See details, below.) It is only this system that I will refer to as the toroidal coordinate system; all other functions that trace out toroidal surfaces but that don't conform precisely to Morse & Feshbach's coordinate system will be referred to as toroidal-like.

I became particularly interested in this idea while working with Howard Cohl (when he was an LSU graduate student). Howie's dissertation research uncovered a Compact Cylindrical Greens Function technique for evaluating Newtonian potentials of rotationally flattened (especially axisymmetric) configurations.2,3 The technique involves a multipole expansion in terms of half-integer-degree Legendre functions of the <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> kind — see NIST digital library discussion — where, we have discovered, the argument of this special function is a function only of the radial coordinate of Morse & Feshbach's orthogonal toroidal coordinate system — see more on this, below.

Statement of the Problem

Expression for the Axisymmetric Potential

Cohl & Tohline (1999; hereafter CT99) derive an expression for the Newtonian gravitational potential in terms of a Compact Cylindrical Green's Function expansion. They show — see, for example, their equation (31) — that when expressed in terms of cylindrical coordinates, the potential at any meridional location, <math>\varpi = R_*</math> and <math>~Z = Z_*</math>, due to an axisymmetric mass distribution, <math>~\rho(\varpi, Z)</math>, is

<math> \Phi(R_*,Z_*) = - \frac{2Gq_0}{R_*^{1/2}} , </math>

where,

<math> q_0 = \int_\Sigma \varpi^{1/2} Q_{-1/2}(\Chi) \rho(\varpi, Z) d\sigma, </math>

<math>~d\sigma = d\varpi dZ</math> is a differential area element in the meridional plane, and the dimensionless argument (the modulus) of the special function, <math>~Q_{-1/2}</math>, is,

<math> \Chi \equiv \frac{R_*^2 + \varpi^2 + (Z_* - Z)^2}{2R_* \varpi} . </math>

Next, following the lead of CT99, we note that according to the Abramowitz & Stegun (1965),

<math>Q_{-1/2}(\Chi) = \mu K(\mu) \, ,</math>

where, the function <math>~K(\mu)</math> is the complete elliptical integral of the first kind and, for our particular problem,

|

<math>~\mu^2</math> |

<math>~\equiv</math> |

<math>~2(1+\Chi)^{-1}</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ 2\biggl[ 1+\frac{R_*^2 + \varpi^2 + (Z_* - Z)^2}{2R_* \varpi}\biggr]^{-1} </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ \biggl[\frac{4R_*\varpi}{(R_* + \varpi)^2 + (Z_* - Z)^2} \biggr] \, . </math> |

Hence, we can write,

<math> q_0 = \int\int \varpi^{1/2} \mu K(\mu) \rho(\varpi, Z) d\varpi dZ \, . </math>

As has been explained in an accompanying set of notes, this is precisely the same expression for the gravitational potential that A. Trova, J.-M. Huré and F. Hersant (2012; MNRAS, 424, 2635) used in their study of the potential of self-gravitating, axisymmetric discs.

Our objective, here, is to examine whether or not it might be advantageous to transform this expression to one in which the double integral is performed on a toroidal, rather than a cylindrical, coordinate system.

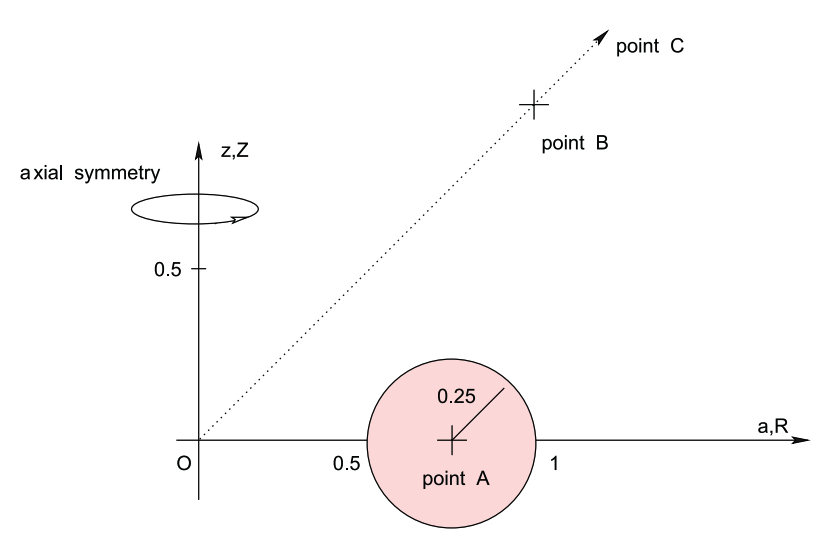

Chosen Test Mass Distribution

For purposes of illustration, we will follow the lead of Trova, Huré & Hersant (2012) — see the left-hand panel of the following figure ensemble — and seek to determine the gravitational potential, both inside and outside, of a uniform-density, equatorial-plane torus whose (pink) meridional cross-section is exactly a circle. More specifically, as illustrated in our Figure 1 — see the right-hand panel of the following figure ensemble — at all azimuthal angles, a cross-section through the (pink) torus is prescribed by the familiar algebraic expression for an off-center circle, namely,

|

<math>~(\varpi_t - \varpi)^2 + Z^2</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~r_t^2 \, .</math> |

Everywhere inside this toroidal surface we set <math>~\rho(\varpi, Z) = \rho_0</math>, that is, the density is uniform with the value, <math>~\rho_0</math>.

|

Figure 4 extracted without modification from p. 2640 of Trova, Huré & Hersant (2012)

"The Potential of Discs from a 'Mean Green Function' "

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 424, pp. 2635-2645 © RAS |

Our Figure 1 |

|---|---|

Notice that another off-center circle — this one with a purple perimeter and otherwise white, rather than pink — appears in our Figure 1 diagram. In the discussion that follows, it will be used to represent the meridional-plane cross-section of one axisymmetric surface in an MF53 toroidal-coordinate system. Here we simply point out that this "surface" is also prescribed by an algebraic expression for an off-center circle, namely,

|

<math>~(R_0 - \varpi)^2 + (Z_0 - Z)^2</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~r_0^2 \, .</math> |

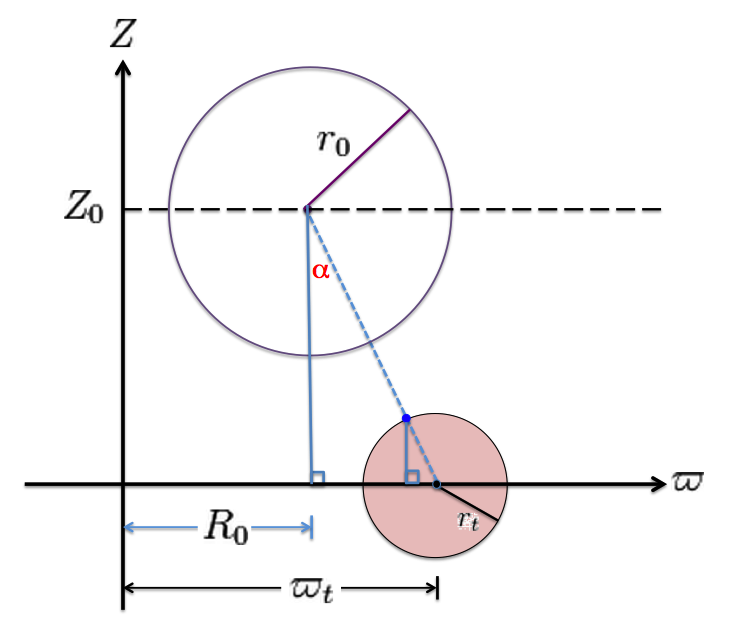

Toroidal Coordinates

Properties

Here we highlight certain properties and features of the MF53 toroidal coordinate system; more details can be found in a related set of our online notes. Most importantly in the context of our discussion, if (at all azimuthal angles) the origin of the toroidal coordinate system is placed at the cylindrical-coordinate location, <math>~(a, Z_0), </math> the pair of orthogonal coordinates, <math>~(\xi_1, \xi_2)</math>, is related to the cylindrical coordinate pair, <math>~(\varpi, Z)</math>, via the expressions,

| [MF53] | Wikipedia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

<math> ~\frac{\varpi}{a} </math> |

<math> ~= </math> |

<math> ~\frac{(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}}{\xi_1 - \xi_2} </math> |

<math> ~= </math> |

<math> ~\frac{\sinh\tau}{\cosh\tau - \cos\theta} \, , </math> |

|

<math> ~\frac{(Z_0 - Z)}{a} </math> |

<math> ~= </math> |

<math> ~\pm~\frac{(1-\xi_2^2)^{1/2}}{\xi_1 - \xi_2} </math> |

<math> ~= </math> |

<math> ~\frac{\sin\theta}{\cosh\tau - \cos\theta} \, . </math> |

An off-center circle — such as the white circle with purple perimeter depicted in our Figure 1 diagram — is generated if a value of the "radial" coordinate, <math>~\xi_1</math>, is chosen from within the range,

| [MF53] | Wikipedia | |

|---|---|---|

|

<math>~+1 \leq \xi_1 < \infty</math> |

or, equivalently |

<math>~0 \leq \tau < \infty \, ,</math> |

and held fixed while the "angular" coordinate, <math>~\xi_2</math>, is varied over the range,

| [MF53] | Wikipedia | |

|---|---|---|

|

<math>~ -1 \leq \xi_2 \leq +1</math> |

or, more completely |

<math>~-\pi < \theta \leq \pi</math> |

Hereafter, we will refer to this <math>~\xi_1</math> = constant circle as a "<math>\xi_1</math>-circle." A <math>\xi_1</math>-circle of radius zero and, hence, the origin of the toroidal coordinate system is associated with the upper limiting value of the radial coordinate, namely, <math>~\xi_1 = \infty</math>; as the value of <math>~\xi_1</math> is decreased monotonically, the radius of the circle (for example, the circle of radius, <math>~r_0</math>, in our Figure 1) steadily grows; and the radius of this circle becomes infinite at the radial coordinate's other limiting value, <math>~\xi_1 = 1</math>.

In the <math>~Z = Z_0</math> plane, the location of the inner and outer edges of the toroidal-coordinate surface are determined by setting <math>~\xi_2 = -1</math> (inner) and <math>~\xi_2 = +1</math> (outer). Hence,

|

<math> ~\biggl(\frac{\varpi}{a}\biggr)_\mathrm{inner} </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math> ~\frac{(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}}{\xi_1 +1} = \biggl[\frac{(\xi_1 - 1)}{(\xi_1 + 1)} \biggr]^{1/2} \, , </math> |

|

<math> ~\biggl(\frac{\varpi}{a}\biggr)_\mathrm{outer} </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math> ~\frac{(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}}{\xi_1 - 1} = \biggl[\frac{(\xi_1 + 1)}{(\xi_1 - 1)} \biggr]^{1/2} \, . </math> |

Hence, also, the (cylindrical) radial location of the "center" of each toroidal-coordinate surface — labeled <math>~R_0</math> in our Figure 1 — is given by the expression,

<math> R_0 = \frac{a}{2} \biggl[ \biggl(\frac{\varpi}{a}\biggr)_\mathrm{outer} + \biggl(\frac{\varpi}{a}\biggr)_\mathrm{inner} \biggr] = \frac{a\xi_1}{(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}} \, , </math>

and the surface's cross-sectional radius — labeled <math>~r_0</math> in our Figure 1 — is given by the expression,

<math> r_0 = \frac{a}{2} \biggl[ \biggl(\frac{\varpi}{a}\biggr)_\mathrm{outer} - \biggl(\frac{\varpi}{a}\biggr)_\mathrm{inner} \biggr] = \frac{a}{(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}} \, . </math>

This last expression quantifies, and its simplicity reinforces, our earlier statement; that is, as the value of <math>~\xi_1</math> is decreased monotonically, the radius of the circle, <math>~r_0</math>, steadily grows. The next-to-last expression makes it clear, as well, that <math>~R_0</math> grows larger and, therefore, the location of the center of a <math>\xi_1</math>-circle shifts farther away from the symmetry axis as the value of <math>~\xi_1</math> is decreased. Notice that, for any off-center circle, the ratio of these to lengths gives the value of the toroidal-coordinate system's dimensionless "radial" coordinate, that is,

|

<math>~\frac{R_0}{r_0} </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl[\frac{a\xi_1}{(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}}\biggr] \biggl[ \frac{(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}}{a}\biggr] = \xi_1 \, .</math> |

Notice, furthermore, that there is a particular combination of these two lengths that is independent of <math>~\xi_1</math>, namely,

|

<math>~r_0 \biggl[\biggl( \frac{R_0}{r_0} \biggr)^2 - 1 \biggr]^{1/2} </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{a}{(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}} \biggl[\xi_1^2 - 1 \biggr]^{1/2} = a \, .</math> |

This is a manner in which one can determine the radial position, <math>~a</math>, of the origin of the toroidal coordinate system that could legitimately be associated with any particular off-center circle, such as the white circle with a purple perimeter drawn in our Figure 1.

Connection With the Physical Problem

Earlier, we stated that the off-center circle with purple perimeter displayed in Figure 1 is prescribed by the algebraic expression,

|

<math>~(R_0 - \varpi)^2 + (Z_0 - Z)^2</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~r_0^2 \, .</math> |

Let's plug in the "toroidal-coordinate" expressions for each parameter that appears on the left-hand side of this relation and see whether, after simplification, it reduces to the right-hand side.

|

LHS |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~(R_0 - \varpi)^2 + (Z_0 - Z)^2</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl[ \frac{a\xi_1}{(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}} - \frac{a(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}}{\xi_1 - \xi_2} \biggr]^2 + \biggl[\pm~\frac{a(1-\xi_2^2)^{1/2}}{\xi_1 - \xi_2}\biggr]^2</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{a^2}{(\xi_1^2 - 1)} \biggl\{ \biggl[ \xi_1 - \frac{(\xi_1^2 - 1)}{\xi_1 - \xi_2} \biggr]^2 + \biggl[\frac{(1-\xi_2^2)^{1/2}(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2} }{\xi_1 - \xi_2}\biggr]^2 \biggr\} </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{a^2}{(\xi_1^2 - 1)(\xi_1-\xi_2)^2} \biggl\{ \biggl[ \xi_1(\xi_1-\xi_2) - (\xi_1^2 - 1) \biggr]^2 + (1-\xi_2^2)(\xi_1^2 - 1) \biggr\} </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{a^2}{(\xi_1^2 - 1)(\xi_1-\xi_2)^2} \biggl[ ( 1-\xi_1\xi_2 )^2 + (\xi_1^2 - 1 -\xi_1^2\xi_2^2 + \xi_2^2) \biggr] </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{a^2}{(\xi_1^2 - 1)(\xi_1-\xi_2)^2} \biggl[ \xi_1^2 -2\xi_1\xi_2 + \xi_2^2 \biggr] </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{a^2}{(\xi_1^2 - 1)} \, . </math> |

This, indeed, equals the right-hand side of the relation, which is, <math>~r_0^2</math>. It all nicely checks out!

Next, taking a hint from the EUREKA! moment recorded in our accompanying notes, let's rewrite the function <math>~\Chi</math> in terms of toroidal rather than cylindrical coordinates, where <math>~\Chi</math> is the argument of the special function, <math>~Q_{-1/2}</math>, that appears in the above definition of <math>~q_0</math>. More specifically, let's assume that the coordinate location at which the gravitational potential is to be evaluated, <math>~(R_*, Z_*)</math>, is taken to be the cylindrical-coordinate location of the origin of the toroidal coordinate system, <math>~(a, Z_0)</math>. Given this association, we can write,

|

<math>~\Chi </math> |

<math>~\equiv</math> |

<math>~\frac{R_*^2 + \varpi^2 + (Z_* - Z)^2}{2R_* \varpi}</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{a^2 + \varpi^2 + (Z_0 - Z)^2}{2a \varpi}</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{1 + (\varpi/a)^2 + [(Z_0 - Z)/a]^2}{2(\varpi/a) }</math> |

|

<math>~\Rightarrow~~~~ \Chi^2 </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl[ 2 \biggl( \frac{\varpi}{a} \biggr) \biggr]^{-2} \biggl\{ 1 + \biggl(\frac{\varpi}{a} \biggr)^2 + \biggl[\frac{(Z_0 - Z)}{a} \biggr]^2 \biggr\}^2 </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl[ \frac{2(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}}{\xi_1 - \xi_2} \biggr]^{-2} \biggl\{ 1 + \biggl[\frac{(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}}{\xi_1 - \xi_2} \biggr]^2 + \biggl[\pm~\frac{(1-\xi_2^2)^{1/2}}{\xi_1 - \xi_2} \biggr]^2 \biggr\}^2 </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{(\xi_1 - \xi_2)^2}{4(\xi_1^2 - 1)} \biggl[ 1 + \frac{(\xi_1^2 - 1)}{(\xi_1 - \xi_2)^2} + \frac{(1-\xi_2^2)}{(\xi_1 - \xi_2)^2} \biggr]^2 </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{1}{4(\xi_1^2 - 1)(\xi_1 - \xi_2)^2} \biggl[ (\xi_1 - \xi_2)^2 + (\xi_1^2 - 1) + (1-\xi_2^2) \biggr]^2 </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{[ 2\xi_1(\xi_1 - \xi_2 ) ]^2}{4(\xi_1^2 - 1)(\xi_1 - \xi_2)^2} </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{\xi_1^2}{\xi_1^2 - 1} \, . </math> |

Hence, when the function, <math>~q_0</math>, is rewritten in terms of the elliptic integral of the first kind, <math>~K(\mu)</math>, the modulus of <math>~K</math> can be written as,

|

<math>~\mu^2</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2[1+\Chi]^{-1}</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2\biggl[1+\frac{\xi_1}{(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}} \biggr]^{-1}</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{2(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}}{(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}+\xi_1} \, .</math> |

This is the key result motivating the use of a toroidal coordinate system to evaluate the gravitational potential: When expressed in an appropriately defined toroidal coordinate system, the modulus of the special function is a function of one, rather than two, spatial coordinates. This gives some hope that the integral over the second (angular) coordinate, <math>~\xi_2</math>, can be completed analytically, giving rise to an expression for the gravitational potential whose evaluation only requires numerical integration over a single (radial) coordinate, <math>~\xi_1</math>.

Finally, drawing on discussion in our accompanying set of notes, we recognize that, expressed in terms of toroidal coordinates, the differential area element in the meridional plane is,

|

<math>~d\sigma</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ a^2 \biggl[ \frac{d\xi_1}{(\xi_1 - \xi_2)(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}} \biggr] \biggl[ \frac{d\xi_2}{(\xi_1 - \xi_2)(1-\xi_2^2)^{1/2}} \biggr] \, . </math> |

Putting everything together, then, the (indefinite) integral expression for <math>~q_0</math>, expressed in terms of toroidal-coordinates, is,

|

<math>~q_0</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ \int \int \biggl[ \frac{a(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}}{\xi_1 - \xi_2} \biggr]^{1/2} \mu K(\mu) \rho(\xi_1, \xi_2) \biggl[ \frac{a}{(\xi_1 - \xi_2)(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}} \biggr] \biggl[ \frac{a}{(\xi_1 - \xi_2)(1-\xi_2^2)^{1/2}} \biggr] d\xi_1 d\xi_2 </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~a^{5/2} \int (\xi_1^2 - 1)^{-1/4} \mu K(\mu) d\xi_1 \int \rho(\xi_1, \xi_2) \biggl[ \frac{d\xi_2}{(\xi_1 - \xi_2)^{5/2}(1-\xi_2^2)^{1/2}} \biggr] </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2^{1/2} a^{5/2} \int [ (\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}+\xi_1 ]^{-1/2} K(\mu) d\xi_1 \int \rho(\xi_1, \xi_2) \biggl[ \frac{d\xi_2}{(\xi_1 - \xi_2)^{5/2}(1-\xi_2^2)^{1/2}} \biggr] \, . </math> |

Making the substitution,

<math>~\xi_2~ \rightarrow ~ \sin\theta</math> <math>~\Rightarrow</math> <math>~d\xi_2~ \rightarrow ~ \cos\theta ~d\theta</math> ,

and,

<math>~\xi_1~ \rightarrow ~ \cosh x</math> <math>~\Rightarrow</math> <math>~d\xi_1~ \rightarrow ~ \sinh x ~dx</math> ,

gives,

|

<math>~q_0</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2^{1/2} a^{5/2} \int\limits_{x_\mathrm{min}}^{x_\mathrm{max}} \frac{K(\mu) \sinh x ~dx}{( \sinh x+\cosh x )^{1/2}} \int\limits_{\theta_\mathrm{min}}^{\theta_\mathrm{max}} \rho(\xi_1, \theta) \biggl[ \frac{d\theta}{(\xi_1 - \sin\theta)^{5/2}} \biggr] \, , </math> |

where, written in terms of <math>~x</math>,

|

<math>~\mu</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ \biggl[\frac{2\sinh x}{\sinh x+\cosh x}\biggr]^{1/2} </math> |

and where we have now explicitly introduced four parameters to set definite limits on the nested pair of integrations.

Perform Angular Integration Over Test Mass Distribution

While, in principle, the pair of nested integrals must be carried out over all of space using the limits,

<math>~\xi_1|_\mathrm{min} = 1 \, , ~\xi_1|_\mathrm{max} = \infty \, , ~\theta_\mathrm{min} = - \tfrac{\pi}{2} \, ,</math> and <math>~\theta_\mathrm{max} = + \tfrac{\pi}{2} \, ,</math>

in practice, the limits should be set to reflect the volume boundaries of the mass distribution that is responsible for generating the gravitational potential. Here we present analytic expressions for these limits in the case of the (pink) toroidal test mass distribution specified above; details regarding the derivation of these expressions can be found in our accompanying set of notes.

Identifying Limits of Integration

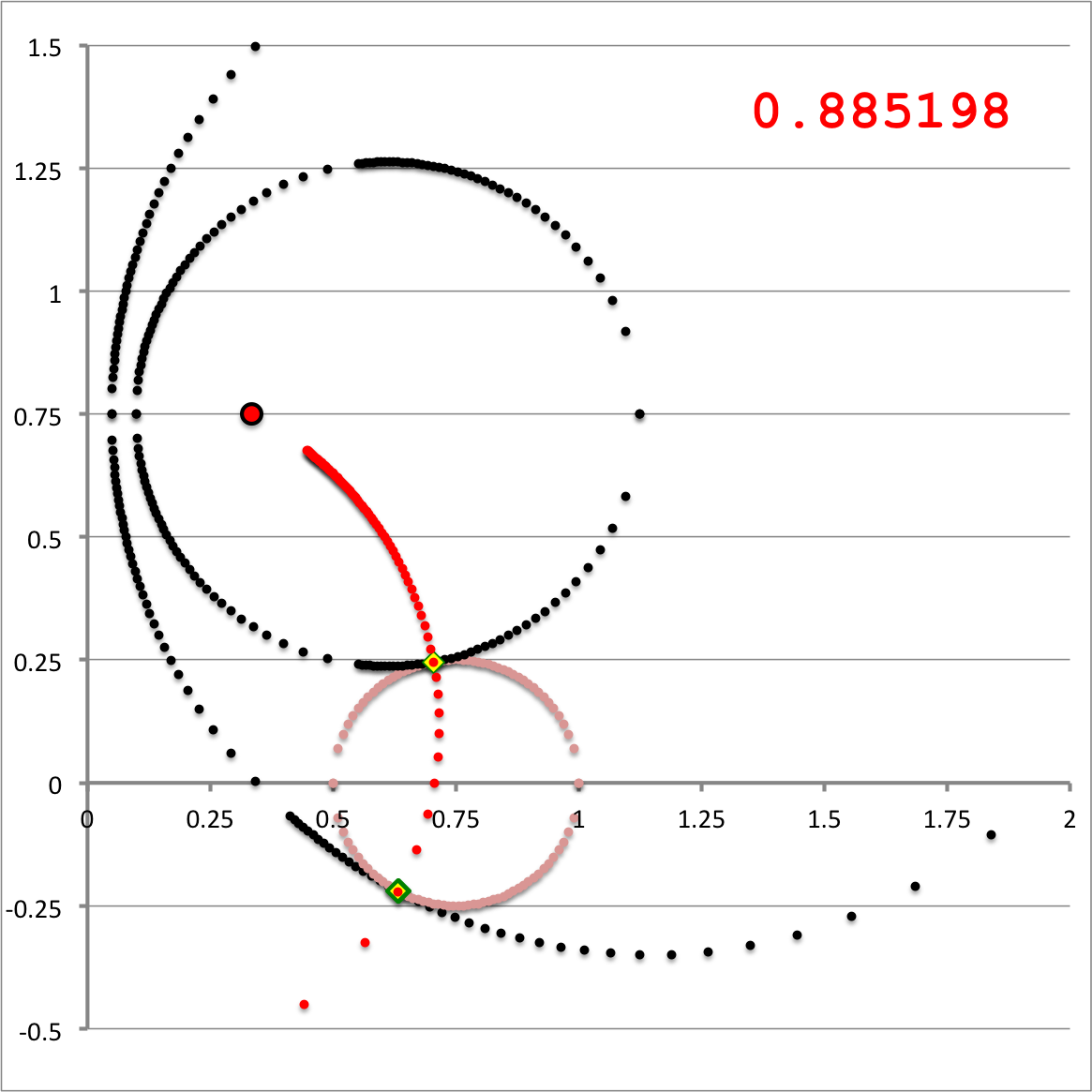

| Figure 2 |

|---|

The animation shown here in Figure 2 builds upon the configuration displayed in our Figure 1, above. It shows a meridional cross-section through the selected (pink) uniform-density, toroidal mass distribution, whose geometric properties are fully determined by specifying values for <math>~\varpi_t</math> and <math>~r_t</math>. (For the example illustrated in Figure 2, we have specified the same values used by Trova, Huré & Hersant (2012) to construct their Figure 4, as reprinted above; namely, <math>~\varpi_t = 3/4</math> and <math>~r_t = 1/4</math>.) Throughout the Figure 2 animation sequence, these two parameters have been fixed — thereby fixing the properties of the (pink) torus — and, in addition, we have fixed the location of the origin of a toroidal coordinate system — identified by the red-filled circular dot. We explicitly associate this coordinate-system origin with the (cylindrical) coordinates of the point in space at which we choose to evaluate the gravitational potential, namely, <math>~(R_*, Z_*) = (a, Z_0)</math>. [For illustration purposes, in Figure 2 we have set <math>~(a, Z_0) = (1/3, 3/4)</math>.]

While the values of the four primary model parameters <math>~(a, Z_0, \varpi_t, r_t)</math> are held fixed, Figure 2 depicts in a quantitatively precise manner how the size of a <math>~\xi_1</math>= constant toroidal surface (the off-center circle traced by the sequence of black dots) varies as the value of the radial coordinate, <math>~\xi_1</math>, is varied. In each frame of the animation sequence, the value of <math>~\xi_1</math> that was used to define the (black) <math>\xi_1</math>-circle is printed in the lower-right corner of the image; additional quantitative details associated with each animation frame can be obtained from the table titled, "Example 2" in our accompanying notes.

As the value of <math>~\xi_1</math> is varied from large values (small black circles) to smaller values (larger black circles), there is a maximum value, <math>~\xi_1|_\mathrm{max}</math>, at which the <math>\xi_1</math>-circle first makes contact with the (pink) equatorial-plane torus, and there is a minimum value, <math>~\xi_1|_\mathrm{min}</math>, at which it makes its final contact. These are the limiting values of the toroidal radial coordinate to be used in the integration that produces <math>~q_0</math>. At all values within the parameter range,

<math>~\xi_1|_\mathrm{max} > \xi_1 > ~\xi_1|_\mathrm{min} \, ,</math>

the <math>\xi_1</math>-circle intersects the surface of the torus in two locations, defined by two different values of the associated angular coordinate, <math>~\xi_2</math>. In each frame of the animation, points of intersection are marked with small yellow diamonds; the coordinates of these points of intersection are listed in the table associated with example 2, in our accompanying notes. For each relevant value of <math>~\xi_1</math>, these are the limiting values of the toroidal angular coordinate to be used in the integration that produces <math>~q_0</math>. It should be realized that, at the first and final points of contact, the two values of <math>~\xi_2</math> are degenerate.

Notice in the animation that, while the origin of the selected toroidal coordinate system (the filled red dot) remains fixed, the center of the <math>\xi_1</math>-circle does not remain fixed. In order to highlight this behavior, the location of the center of the <math>\xi_1</math>-circle has been marked by a filled, light-blue square and, in keeping with the earlier Figure 1 diagram, a vertical, light-blue line connects this center to the equatorial plane of the cylindrical coordinate system.

Associated Analytic Expressions

We define the following terms that are functions only of the four principal model parameters, <math>~(a, Z_0, \varpi_t, r_t)</math>, and therefore can be treated as constants while carrying out the pair of nested integrals that determine <math>~q_0</math>:

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Then,

<math>\xi_1|_\mathrm{max} = \biggl[1-\biggl( \frac{a}{\varpi_t-\beta_+} \biggr)^2 \biggr]^{-1/2} \approx 1.1927843</math> and <math>\xi_1|_\mathrm{min} = \biggl[1-\biggl( \frac{a}{\varpi_t-\beta_-} \biggr)^2 \biggr]^{-1/2} \approx 1.0449467\, ,</math>

which implies,

<math>x_\mathrm{max} = \tanh^{-1}\biggl( \frac{a}{\varpi_t-\beta_+} \biggr) \approx 0.61137548 </math> and <math>x_\mathrm{min} = \tanh^{-1}\biggl( \frac{a}{\varpi_t-\beta_-} \biggr) \approx 0.29871048 \, .</math>

Also let,

<math>~\xi_1 \rightarrow \cosh x \, ,</math> in which case, <math>~(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2} \rightarrow \sinh x</math> and, <math>~(1-\xi_1^{-2})^{-1/2} = \frac{\xi_1}{(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}} \rightarrow \coth x\, ,</math>

and define,

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Figure 3 |

|---|

Then, for each value of the radial coordinate, <math>~\xi_1 = \cosh x</math>, within the range,

<math>~x_\mathrm{max} \geq x \geq x_\mathrm{min} \, ,</math>

the limiting values <math>~(\pm)</math> of the angular coordinate are,

|

<math>~\xi_2\biggr|_\pm</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ \cosh x - \sinh x \biggl( \frac{2a^2}{\kappa}\cdot \frac{A}{B} \biggr) \biggl[1 \pm \sqrt{1-\frac{AC}{B^2}}\biggr]^{-1} \, . </math> |

This provides the desired analytic expression for the two limits of integration over the angular coordinate that must be carried out in order to evaluate the key function, <math>~q_0</math>, in our determination of the gravitational potential at the cylindrical-coordinate location, <math>~(R_*, Z_*) = (a, Z_0)</math>.

We should note that at both limits — that is, at the two values of <math>~x</math> for which the functions <math>~A</math> and <math>~B</math> have been evaluated, immediately above — the ratio under the square-root,

<math>~\frac{AC}{B^2} = 1 \, .</math>

Hence, at both radial-coordinate limits, the two angular-coordinate limits, <math>~\xi_2|_\pm</math>, are degenerate. Furthermore, we have discovered that the value of this degeneracy angle is exactly the same at both radial-coordinate limits; specifically, we find that, for our chosen test-mass distribution,

<math>~\xi_2\biggr|_\mathrm{deg} \approx 0.885198 \, .</math>

This means that exactly the same <math>\xi_2</math>-constant, toroidal-coordinate "line" intersects the surface of the (pink) test-mass torus at both the point of first contact <math>~(\xi_1|_\mathrm{max})</math> and the point of final contact <math>~(\xi_1|_\mathrm{min})</math>. In order to illustrate this, this particular <math>\xi_2</math>-constant "line" has been traced by a sequence of red dots in Figure 3. As just described, it passes smoothly through the points on the surface of the (pink) torus where the <math>\xi_1</math>-circles make first (small black-dotted circle) and final (large black-dotted circle) contact.

Integrate

Because the density is uniform throughout our test model torus, it can be pulled out of both integrals. In combination with the limits of integration just derived, we can therefore write,

|

<math>~q_0</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2^{1/2} a^{5/2}\rho_0 \int\limits_{\tanh^{-1}[a/(\varpi_t-\beta_-)]}^{\tanh^{-1}[a/(\varpi_t-\beta_+)]} \frac{K(\mu) \sinh x ~dx}{( \sinh x+\cosh x )^{1/2}} \int\limits_{\sin^{-1}(\xi_2|_-)}^{\sin^{-1}(\xi_2|_+)} \biggl[ \frac{d\theta}{(\xi_1 - \sin\theta)^{5/2}} \biggr] \, . </math> |

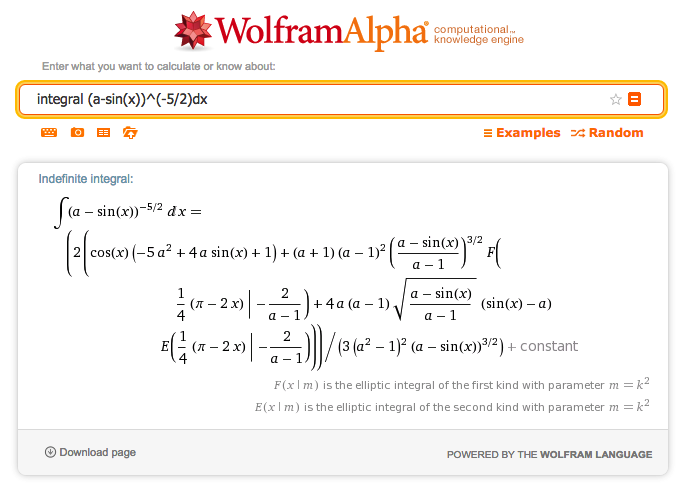

Now, using WolframAlpha's online integrator, we find …

Hence, the inner integral over our toroidal system's angular coordinate gives,

|

<math>~\int\limits_{\sin^{-1}(\xi_2|_-)}^{\sin^{-1}(\xi_2|_+)} \biggl[ \frac{d\theta}{(\xi_1 - \sin\theta)^{5/2}} \biggr]</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl\{ \frac{2}{3(\xi_1^2-1)^2 (\xi_1-\sin\theta)^{3/2}} \biggl[ \cos\theta ( -5\xi_1^2 + 4\xi_1\sin\theta + 1) </math> |

|

|

|

<math>~ + (\xi_1+1)(\xi_1-1)^2 \biggl( \frac{\xi_1-\sin\theta}{\xi_1-1} \biggr)^{3/2} F\biggl(\frac{\pi - 2\theta}{4} \biggr| \frac{-2}{\xi_1-1} \biggr) </math> |

|

|

|

<math>~ + 4\xi_1(\xi_1-1)(\sin\theta-\xi_1) \biggl( \frac{\xi_1-\sin\theta}{\xi_1-1} \biggr)^{1/2} E\biggl(\frac{\pi - 2\theta}{4} \biggr| \frac{-2}{\xi_1-1} \biggr) \biggr] \biggr\}_{\sin^{-1}(\xi_2|_-)}^{\sin^{-1}(\xi_2|_+)} </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl\{ \biggl[ \frac{2[1-(\xi_2|_+)^2] ( -5\xi_1^2 + 4\xi_1\xi_2|_+ + 1)}{3(\xi_1^2-1)^2 (\xi_1-\xi_2|_+)^{3/2}} \biggr] </math> |

|

|

|

<math>~ + \tfrac{2}{3} (\xi_1-1)^{-3/2}\biggl[ (\xi_1+1) F\biggl(\frac{\cos^{-1}(\xi_2|_+)}{2} \biggr| \frac{2}{1-\xi_1} \biggr) - 4 \xi_1 E\biggl(\frac{\cos^{-1}(\xi_2|_+)}{2}\biggr| \frac{2}{1-\xi_1} \biggr) \biggr] \biggr\} </math> |

|

|

|

<math>~- \biggl\{ \biggl[ \frac{2[1-(\xi_2|_-)^2] ( -5\xi_1^2 + 4\xi_1\xi_2|_- + 1)}{3(\xi_1^2-1)^2 (\xi_1-\xi_2|_-)^{3/2}} \biggr] </math> |

|

|

|

<math>~ + \tfrac{2}{3} (\xi_1-1)^{-3/2}\biggl[ (\xi_1+1) F\biggl(\frac{\cos^{-1}(\xi_2|_-)}{2} \biggr| \frac{2}{1-\xi_1} \biggr) - 4 \xi_1 E\biggl(\frac{\cos^{-1}(\xi_2|_-)}{2}\biggr| \frac{2}{1-\xi_1} \biggr) \biggr] \biggr\} </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\tfrac{2}{3} (\xi_1-1)^{-3/2}\biggl\{ \biggl[ \frac{[1-(\xi_2|_+)^2] ( -5\xi_1^2 + 4\xi_1\xi_2|_+ + 1)}{(\xi_1-1)^{1/2} (\xi_1+1)^2 (\xi_1-\xi_2|_+)^{3/2}} \biggr] - \biggl[ \frac{[1-(\xi_2|_-)^2] ( -5\xi_1^2 + 4\xi_1\xi_2|_- + 1)}{(\xi_1-1)^{1/2} (\xi_1+1)^2(\xi_1-\xi_2|_-)^{3/2}} \biggr] </math> |

|

|

|

<math>~ + \biggl[ (\xi_1+1) F\biggl(\sin^{-1}\biggl[\frac{1-\xi_2|_+}{2} \biggr] \biggr| \frac{2}{1-\xi_1} \biggr) - 4 \xi_1 E\biggl(\sin^{-1}\biggl[\frac{1-\xi_2|_+}{2} \biggr]\biggr| \frac{2}{1-\xi_1} \biggr) \biggr] </math> |

|

|

|

<math>~ - \biggl[ (\xi_1+1) F\biggl(\sin^{-1}\biggl[\frac{1-\xi_2|_-}{2} \biggr]\biggr| \frac{2}{1-\xi_1} \biggr) - 4 \xi_1 E\biggl(\sin^{-1}\biggl[\frac{1-\xi_2|_-}{2} \biggr]\biggr| \frac{2}{1-\xi_1} \biggr) \biggr] \biggr\} \, . </math> |

Special Case

In the context of the (pink torus) test-mass distribution being discussed here, a review of the properties of a toroidal coordinate system highlights one particularly interesting (cylindrical) coordinate location at which the gravitational potential should be evaluated:

<math>~\{ R_*, Z_* \} = \biggl\{r_t \biggl[\biggl( \frac{\varpi_t}{r_t} \biggr)^2 - 1 \biggr]^{1/2}, 0 \biggr\} \, .</math>

By placing the origin of the toroidal coordinate system at this and only this location — that is, by setting,

|

<math>~a</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~r_t \biggl[\biggl( \frac{\varpi_t}{r_t} \biggr)^2 - 1 \biggr]^{1/2}</math> |

— the limits of integration can be specified very simply: There is only one <math>\xi_1</math>-circle that intersects the surface of the torus and it does so by, not simply intersecting, but by perfectly aligning with the surface. This perfect overlap with the surface of the torus happens for the coordinate circle associated with,

<math>~\xi_1 = \xi_s \equiv \frac{\varpi_t}{r_t} \, .</math>

All <math>\xi_1</math>-circles larger than this one — that is, all circles corresponding to values of

<math>~\xi_1 < \xi_s </math>

— lie entirely outside of the (pink) torus and therefore need not be included in the integration to determine the gravitational potential; while all <math>\xi_1</math>-circles smaller than this one — that is, all circles corresponding to values of

<math>~\xi_1 \geq \xi_s </math>

— lie entirely inside of the (pink) torus. Hence, in this special case the radial-coordinate integration limits are,

<math>~\xi_1|_\mathrm{min} = \frac{\varpi_t}{r_t} </math> and <math>~~\xi_1|_\mathrm{max} = \infty \, .</math>

Furthermore, because the corresponding <math>\xi_1</math>-circles fall entirely inside (or on the surface of) the torus for all values of <math>~\xi_1</math> in this latter range, the integral over the "angular" toroidal coordinate will have the simple limits,

<math>~\xi_2|_- = -1 ~(\theta_\mathrm{min} = - \tfrac{\pi}{2}) </math> and <math>~\xi_2|_+ = +1~(\theta_\mathrm{max} = + \tfrac{\pi}{2} )\, .</math>

Hence, the inner integral over our toroidal system's angular coordinate gives,

|

<math>~\int\limits_{-\frac{\pi}{2}}^{\frac{\pi}{2}} \biggl[ \frac{d\theta}{(\xi_1 - \sin\theta)^{5/2}} \biggr]</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\tfrac{2}{3} (\xi_1-1)^{-3/2}\biggl\{ (\xi_1+1) \biggl[ F\biggl(0\biggr| \frac{2}{1-\xi_1} \biggr) - F\biggl(\frac{\pi}{2} \biggr| \frac{2}{1-\xi_1} \biggr)\biggr] - 4 \xi_1 \biggl[ E\biggl(0\biggr| \frac{2}{1-\xi_1} \biggr) - E\biggl(\frac{\pi}{2} \biggr| \frac{2}{1-\xi_1} \biggr) \biggr] \biggr\} \, . </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\tfrac{2}{3} (\xi_1-1)^{-3/2}\biggl\{ 4 \xi_1 \biggl[ E\biggl(\frac{2}{1-\xi_1} \biggr)\biggr] - (\xi_1+1) \biggl[ K\biggl(\frac{2}{1-\xi_1} \biggr)\biggr] \biggr\} \, . </math> |

So, we have,

|

<math>~q_0</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2^{1/2} a^{5/2} \rho_0 \int\limits_{\varpi_t/r_t}^\infty \tfrac{2}{3} (\xi_1-1)^{-3/2}[ (\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}+\xi_1 ]^{-1/2} K(\mu) \biggl\{ 4 \xi_1 \biggl[ E\biggl(\frac{2}{1-\xi_1} \biggr)\biggr] - (\xi_1+1) \biggl[ K\biggl(\frac{2}{1-\xi_1} \biggr)\biggr] \biggr\} d\xi_1 \, , </math> |

where,

|

<math>~\mu</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl[ \frac{2(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}}{(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}+\xi_1} \biggr]^{1/2} \, .</math> |

Total Mass

How do I know whether or not I have made mistakes in these derivations? Aside from the published work of Trova, Huré & Hersant (2012), how do I know what the correct answer for the gravitational potential of a uniform-density torus is?

A degree of assurance can be drawn by carrying out a similar pair of nested integrations to determine the total mass (or volume) of the torus that is defined by our chosen test-mass distribution. As can be found in many mathematics handbooks, or online, the volume of our defined torus should be,

<math>~V_\mathrm{torus} = 2\pi^2 \varpi_t r_t^2 \, .</math>

Using Cylindrical Coordinates

Let's start by integrating the three-dimensional volume element, <math>~dV_{3D}</math>, over the azimuthal angle to obtain an expression for the two-dimensional differential volume element that is written in terms of the meridional-plane differential area, <math>~d\sigma</math>, as used in our definition of <math>~q_0</math>, above. Using the notation of MF53 (but employing the opposite sign convention from them), in cylindrical coordinates we have,

|

<math>~dV_{3D}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~- [h_1 d\xi_1 ] [h_2 d\xi_2] [h_3 d\xi_3] </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~-~d\xi_1 \biggl[\frac{\xi_1}{\sqrt{1-\xi_2^2}} d\xi_2 \biggr] d\xi_3 </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~-~d\varpi \biggl[\frac{\varpi d(\cos\varphi) }{\sqrt{1-\cos^2\varphi}} \biggr] dz </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>+~[\varpi d\varphi ] d\sigma \, , </math> |

where, as before in cylindrical coordinates, <math>~d\sigma = d\varpi dz</math>. From this we obtain,

|

<math>~dV_{2D}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\varpi d\sigma \int_0^{2\pi} d\varphi </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2\pi \varpi d\sigma \, .</math> |

Now in order to finish the volume integration, we need the limits of integration in the meridional plane. These can be obtained from the above algebraic description of the (pink) test-mass torus as an off-center circle. Specifically, we have,

|

<math>~V</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2\pi \int\limits_{(\varpi_t - r_t)}^{(\varpi_t + r_t)} \varpi d\varpi \int\limits_{-\sqrt{r_t^2 - (\varpi_t - \varpi)^2}}^{\sqrt{r_t^2 - (\varpi_t - \varpi)^2}} dz </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

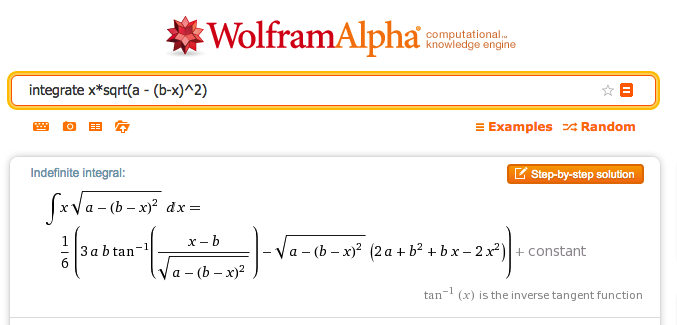

<math>~4\pi \int\limits_{(\varpi_t - r_t)}^{(\varpi_t + r_t)} \sqrt{r_t^2 - (\varpi_t - \varpi)^2} \varpi d\varpi </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{2\pi}{3} \biggl\{ 3r_t^2 \varpi_t \tan^{-1}\biggl[ \frac{\varpi - \varpi_t}{ \sqrt{r_t^2 - (\varpi_t - \varpi)^2 }} \biggr] - [r_t^2 - (\varpi_t - \varpi)^2 ]^{1/2}~(2r_t^2 + \varpi_t^2 + \varpi_t \varpi - 2\varpi^2) \biggr\}_{(\varpi_t - r_t)}^{(\varpi_t + r_t)} </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math> ~\frac{2\pi}{3} \biggl\{3r_t^2 \varpi_t \tan^{-1}\biggl[ \frac{r_t}{0 } \biggr] - 0 \biggr\} -~\frac{2\pi}{3} \biggl\{3r_t^2 \varpi_t \tan^{-1}\biggl[ \frac{-r_t}{0} \biggr] - 0 \biggr\} </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math> ~\frac{2\pi}{3} \biggl[ 3r_t^2 \varpi_t \biggl(\frac{\pi}{2}\biggr) \biggr] +~\frac{2\pi}{3} \biggl[ 3r_t^2 \varpi_t \biggl(\frac{\pi}{2}\biggr) \biggr] </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math> ~2\pi^2 r_t^2 \varpi_t \, , </math> |

where we have carried out the second integration using the WolframAlpha online integral calculator:

This is the answer for the volume of a torus that we expected. Good!

Using Toroidal Coordinates with Special Alignment

If, instead, we use a toroidal coordinate system, we have (see p. 666 of MF53),

|

<math>~dV_{3D}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~- [h_1 d\xi_1 ] [h_2 d\xi_2] [h_3 d\xi_3] </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~-~\biggl[ \frac{a d\xi_1}{ (\xi_1-\xi_2)\sqrt{\xi_1^2-1} } \biggr]~ \biggl[\frac{a d\xi_2}{ (\xi_1-\xi_2)\sqrt{1-\xi_2^2} } \biggr] ~ \biggl[ \biggl( \frac{\xi_1^2 - 1}{1 - \xi_3^2} \biggr)^{1/2} \frac{a d\xi_3}{(\xi_1-\xi_2)} \biggr]</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~- d\sigma~ \biggl[ \frac{a(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}}{(\xi_1-\xi_2)} \frac{d(\cos\varphi)}{\sqrt{1 - \cos^2\varphi}} \biggr]</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>+~[\varpi d\varphi ] d\sigma \, , </math> |

where, as employed above, a differential area element in the meridional plane of a toroidal-coordinate system is,

|

<math>~d\sigma</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~a^2\biggl[ \frac{d\xi_1}{ (\xi_1-\xi_2)\sqrt{\xi_1^2-1} } \biggr]~ \biggl[\frac{d\xi_2}{ (\xi_1-\xi_2)\sqrt{1-\xi_2^2} } \biggr] \, . </math> |

As in the case of the cylindrical coordinate system, because the torus is axisymmetric, integration over the azimuthal angular coordinate in a toroidal coordinate system gives,

|

<math>~dV_{2D}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\varpi d\sigma \int_0^{2\pi} d\varphi </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2\pi \varpi d\sigma \, .</math> |

| Cross-check: Wikipedia's Differential Volume Element | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

where,

and, as above,

Hence, in agreement with the expression derived using the notation of MF53,

|

Now, if we choose a toroidal coordinate system whose origin is located exactly as defined in our special case, above, the radial-coordinate integration limits should be,

<math>~\xi_1|_\mathrm{min} = \frac{\varpi_t}{r_t} </math> and <math>~~\xi_1|_\mathrm{max} = \infty \, ;</math>

and the integral over the "angular" toroidal coordinate will have the simple limits,

<math>~\xi_2|_- = -1 </math> and <math>~\xi_2|_+ = +1 \, .</math>

So, integration over the remaining two (meridional-plane) coordinates gives,

|

<math>~V</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2\pi \int_\Sigma \varpi d\sigma </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2\pi a^3 \int\limits_{\varpi_t/r_t}^\infty d\xi_1 \int\limits_{-1}^{1} \frac{(\xi_1^2 - 1)^{1/2}}{(\xi_1-\xi_2)} \biggl[ \frac{1}{ (\xi_1-\xi_2)\sqrt{\xi_1^2-1} } \biggr]~ \biggl[\frac{1}{ (\xi_1-\xi_2)\sqrt{1-\xi_2^2} } \biggr] d\xi_2 </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2\pi a^3 \int\limits_{\varpi_t/r_t}^\infty d\xi_1 \int\limits_{-1}^{1} \biggl[\frac{d\xi_2}{ (\xi_1-\xi_2)^3\sqrt{1-\xi_2^2} } \biggr] \, . </math> |

If, following MF53, we make the substitution,

<math>~\xi_2 ~\rightarrow \cos\zeta</math> <math>~\Rightarrow </math> <math>~d\xi_2 ~\rightarrow -\sin\zeta d\zeta \, ,</math>

we can write,

|

<math>~V</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2\pi a^3 \int\limits_{\varpi_t/r_t}^\infty d\xi_1 \int\limits_{0}^{\pi} \biggl[\frac{d\zeta}{ (\xi_1-\cos\zeta)^3 } \biggr] </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\pi a^3 \int\limits_{\varpi_t/r_t}^\infty d\xi_1 \biggl\{ \frac{\sin\zeta [ 4\xi_1^2 - 3\xi_1 \cos\zeta - 1]}{(\xi_1^2-1)^2 (\xi_1 - \cos\zeta)^2} - \frac{2(2\xi_1^2 + 1)\tanh^{-1}\biggl[\frac{(\xi_1 + 1)\tan(\zeta/2)}{\sqrt{1-\xi_1^2}} \biggr]}{(1-\xi_1^2)^{5/2}} \biggr\}_{0}^{\pi} \, , </math> |

where the expression obtained after integrating over <math>~\zeta</math> was obtained from WolframAlpha's online integrator. Note that, carrying out this same integration (specifying wider integration limits based on the toroidal-coordinate specification described in Wikipedia) via multiple steps using the integral tables published by Gradshteyn & Ryzhik, I have obtained,

|

<math>~V</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2\pi a^3 \int\limits_{\varpi_t/r_t}^\infty d\xi_1 \int\limits_{-\pi}^{\pi} \biggl[\frac{d\zeta}{ (\xi_1-\cos\zeta)^3 } \biggr] </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\pi a^3 \int\limits_{\varpi_t/r_t}^\infty d\xi_1 \biggl\{ \frac{\sin\zeta [ 4\xi_1^2 - 3\xi_1 \cos\zeta - 1]}{(\xi_1^2-1)^2 (\xi_1 - \cos\zeta)^2} + \biggl[ \frac{2(2\xi_1^2 + 1)}{(\xi_1^2-1)^{5/2}}\biggr] \tan^{-1}\biggl[\tan\biggl(\frac{\zeta}{2}\biggr) \cdot \frac{(\xi_1 + 1)^{1/2}}{(\xi_1 - 1)^{1/2}} \biggr] \biggr\}_{-\pi}^{\pi} \, . </math> |

There are some differences between the last term obtained via the printed table of integrals versus via WolframAlpha's online integrator. Eventually, I would like to reconcile these differences. In the meantime, the integration limits appear to be a problem because (good news, perhaps) the first term involving <math>~\sin\zeta</math> goes to zero no matter how you slice it; but (bad news), the tangent function in the last term goes to <math>~\pm \infty</math>. So I'm not sure, yet, how to assess this result.

Let's try switching the order of the integrations.

|

<math>~V</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2\pi a^3 \int\limits_{-\pi}^{\pi} d\zeta \int\limits_{\varpi_t/r_t}^\infty \biggl[\frac{d\xi_1}{ (\xi_1-\cos\zeta)^3 } \biggr] </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~- \pi a^3 \int\limits_{-\pi}^{\pi} d\zeta \biggl\{\frac{1}{(\xi_1-\cos\zeta)^2} \biggr\}_{\varpi_t/r_t}^\infty </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\pi a^3 \int\limits_{-\pi}^{\pi} \biggl[\frac{d\zeta}{(\varpi_t/r_t- \cos\zeta)^2} \biggr] </math> |

Another Simple Toroidal-System Alignment

Okay, because the struggle with our previous volume integration had to do with the limits on integration, let's try moving the origin of the toroidal-coordinate system to a position that lies outside of the (pink) torus — let's choose, <math>~0 < a < \varpi_t</math>. For simplicity, however, let's keep the origin in the equatorial plane, that is, set <math>~Z_0 = 0</math>. Given that <math>~\varpi_t = \tfrac{3}{4}</math> and <math>~r_t = \tfrac{1}{4}</math>, from our above derivations of the "radial-coordinate" limits of integration, we know that,

|

<math>~C</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~1 \, ,</math> |

|

<math>~\kappa</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~a^2 - (\varpi_t^2 - r_t^2) = a^2 - \tfrac{1}{2} \, ,</math> |

|

<math>~\beta_\pm</math> |

<math>~\equiv</math> |

<math>~ - \frac{\kappa}{2} \biggl[ \frac{\varpi_t \mp r_t \sqrt{C}}{(\varpi_t + r_t)(\varpi_t - r_t)} \biggr] = -\frac{1}{2}\biggl(a^2 - \frac{1}{2} \biggr)\biggl[ \frac{\varpi_t \mp r_t }{(\varpi_t^2 - r_t^2)} \biggr] </math> |

|

|

<math>~\equiv</math> |

<math>~ \biggl(\frac{1}{2} - a^2\biggr)\biggl[\frac{3}{4} \mp \frac{1}{4} \biggr] \, . </math> |

Let's try, <math>~a = \tfrac{1}{2}</math>, in which case,

<math>\beta_+ = \frac{1}{8}</math> and <math>\beta_- = \frac{1}{4}\, ,</math>

and,

<math>\xi_1|_\mathrm{max} = \biggl[1-\biggl( \frac{a}{\varpi_t-\beta_+} \biggr)^2 \biggr]^{-1/2} = \biggl[1-\biggl( \frac{4}{5} \biggr)^2 \biggr]^{-1/2} </math> and <math>\xi_1|_\mathrm{min} = \biggl[1-\biggl( \frac{a}{\varpi_t-\beta_-} \biggr)^2 \biggr]^{-1/2} \, ,</math>

See Also

References

- Morse, P.M. & Feshmach, H. 1953, Methods of Theoretical Physics — Volumes I and II

- Cohl, H.S. & Tohline, J.E. 1999, ApJ, 527, 86-101

- Cohl, H.S., Rau, A.R.P., Tohline, J.E., Browne, D.A., Cazes, J.E. & Barnes, E.I. 2001, Phys. Rev. A, 64, 052509

|

|---|

|

© 2014 - 2021 by Joel E. Tohline |