Difference between revisions of "User:Tohline/Apps/MaclaurinSpheroids/GoogleBooks"

(→Generate Curve AKG: Finish determining the area under the AKG curve) |

|||

| Line 914: | Line 914: | ||

<math>\mathcal{A} = \frac{\mathrm{AKGC}}{AC} \, ,</math> | <math>\mathcal{A} = \frac{\mathrm{AKGC}}{AC} \, ,</math> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

where the numerator, "AKGC," is the area under the curve, "AKG," and the denominator is the length of the semi-major axis, <math>~a_1</math>. So a key element of Maclaurin's derivation is the proper construction of the curve, "AKG." The key sentence from his § 644 appears to be the following: | where the numerator, "AKGC," is the area under the curve, "AKG," and the denominator is the length of the semi-major axis, <math>~a_1</math>. So a key element of Maclaurin's derivation is the proper construction of the curve, "AKG." The key sentence from his §644 appears to be the following: | ||

[[File:Vol2Par644KeyPhrase.png|400px|thumb|center|Extracted directly from §644 of Maclaurin's Book 1, as digitized by Google]] | [[File:Vol2Par644KeyPhrase.png|400px|thumb|center|Extracted directly from §644 of Maclaurin's Book 1, as digitized by Google]] | ||

| Line 994: | Line 994: | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math>~1 - ~\frac{[1+(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2 (-1 - (1-e^2) ]}{[1+(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2(-1+1-e^2)]}</math> | <math>~1 - ~\frac{[1+(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2 (-1 - (1-e^2) ]}{[1+(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2(-1+1-e^2)]}</math> | ||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~1 - ~\frac{[1-(2-e^2)(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2 ]}{[1-e^2(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2]}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\frac{[1-e^2(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2]-[1-(2-e^2)(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2 ]}{[1-e^2(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2]}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\frac{[2(1-e^2)(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2 ]}{[1-e^2(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2]} \, .</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

In our above figure, this function, <math>~\mathrm{AQ}(z_\mathrm{RN})</math> normalized to <math>~a_1</math>, is delineated by the orange triangles over the coordinate range, <math>~-1 \le z_\mathrm{RN} \le 0</math>. If our interpretation of Maclaurin's discussion is correct, this is precisely the curve in Maclauin's Figure 291, No. 2 that is labeled, "AKG." The area, "AKGC" — which, according to Maclaurin, gives the gravitational acceleration at the pole A — can be determined by carrying out the integral, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\mathcal{A} = \frac{\mathrm{AKGC}}{a_1} </math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\int_{-1}^0 \biggl[\frac{\mathrm{AQ}}{a_1}\biggr]dz_\mathrm{RN} \, .</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

This integral can be more cleanly evaluated if we make the variable substitution, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>u_\mathrm{RN} \equiv 1 + z_\mathrm{RN} \, ,</math> | |||

</div> | |||

with a corresponding shift in the limits of integration from <math>~(-1 \rightarrow 0)</math>, for <math>~z_\mathrm{RN}</math>, to <math>~(0 \rightarrow 1)</math>, for <math>~u_\mathrm{RN}</math>. Specifically, we find, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\mathcal{A} </math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~2(1-e^2) \int_{0}^1 \frac{u_\mathrm{RN}^2 }{1-e^2 u_\mathrm{RN}^2} ~du_\mathrm{RN}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~-2(1-e^2) \biggl[ \frac{u_\mathrm{RN}}{e^2} \biggr]_{0}^1 + \frac{1}{e^4} \int_{0}^1 \frac{du_\mathrm{RN}}{e^{-2}- u_\mathrm{RN}^2} </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~-\frac{2(1-e^2)}{e^2} + \frac{2(1-e^2)}{e^4} \biggl\{ \frac{e}{2} \ln \biggl[ \frac{e^{-2} +u_\mathrm{RN} }{e^{-2} -u_\mathrm{RN} } \biggr] \biggr\}_{0}^1 </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~-\frac{2(1-e^2)}{e^2} + \frac{(1-e^2)}{e^3} \ln \biggl[ \frac{1 + e^{2} }{1-e^{2}} \biggr] \, .</math> | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

This is precisely the result obtained earlier. | |||

=Related Discussions= | =Related Discussions= | ||

Revision as of 02:24, 6 September 2015

Excerpts from A Treatise of Fluxions

|

|---|

| | Tiled Menu | Tables of Content | Banner Video | Tohline Home Page | |

Both Volume I and Volume II of Colin Maclaurin's "A Treatise of Fluxions" can now be accessed online via Google Books. (Check out Wolfram's explanation of the term, fluxion.) In what follows, we provide an abbreviated table of contents for both volumes and present selected excerpts from these volumes.

|

Title Pages with Google-Books Links |

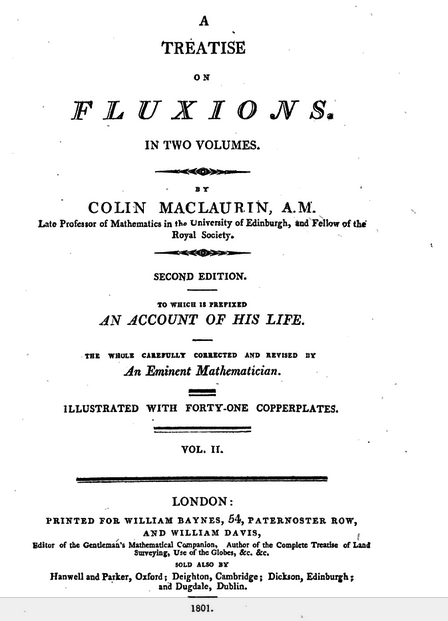

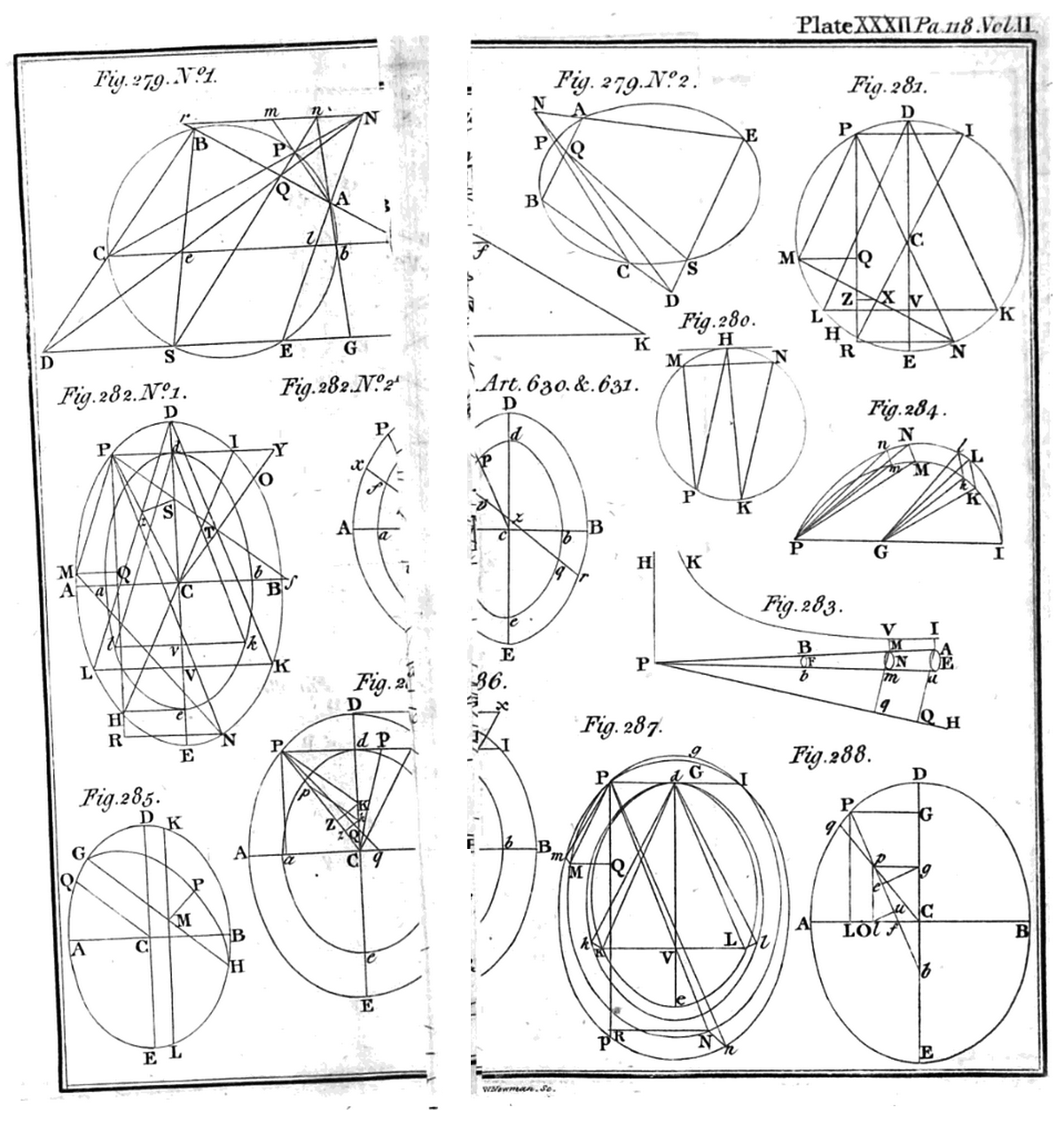

Example Digitized Figure Plates |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Plate XXXII |

Plate XXXIII |

||

As is illustrated in the two righthand panels of the above image quartet (click in one of the panels in order to view a higher-resolution image), each published "Figure Plate" was digitized (by Google Books) in segments that must be digitally pieced together in order to reconstruct some of the individual figures. See, for example, the discussion that references Fig. 282, below.

Volume I

| Dedication (an 18th Century Acknowledgment) | |

| Preface | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| Book 1 (Of the Fluxions of Geometrical Magnitudes) | 51 |

| Chapter I (Of the Grounds of this Method) — §§ 1-77 | 51 |

| Chapter II (Of the Fluxions of plane rectilineal Figures) — §§ 78-104 | 109 |

| Chapter III (Of the Fluxions of plane curvilineal Figures) — §§ 105-123 | 131 |

| Chapter IV (Of the Fluxions of Solids, and of third Fluxions) — §§ 124-139 | 142 |

| Chapter V (Of the Fluxions of Quantities that are in a continued Geometrical Progression, the first term of which is invariable) — §§ 140-150 | 152 |

| Chapter VI (Of Logarithms, and of the Fluxions of logarithmic Quantities) — §§ 151-179 | 158 |

| Chapter VII (Of the Tangents of curve Lines) — §§ 180-214 | 178 |

| Chapter VIII (Of the Fluxions of curve Surfaces) — §§ 215-237 | 199 |

| Chapter IX ([Identifying Extrema and Inflection Points] of Curves that are defined by a common or by a fluxional Equation) — §§ 238-285 | 214 |

| Chapter X (Of the Asymptotes of curve Lines, the Areas bounded by them and …) — §§ 286-362 | 240 |

| Chapter XI (Of the Curvature of Lines … different kinds of Contact [with other Curves] … Caustics … centripetal Forces …) — §§ 363- | 304 |

| · Parabola — §371 | 311 |

| · Any Conic Section — §373 | 312 |

| · The Second Fluxion of a Curve — §384 | 324 |

| · Refraction of Light — §413 | 344 |

| · Centripetal and Centrifugal Forces — §416 | 346 |

| · Gravity — §419 | 348 |

| · Circular Motion — §432 | 356 |

| · When the Center of Forces is the Focus of a Conic Section — §446 | 370 |

| · When Gravity is Uniform or Varies as any Power of the Distance — §458 | 383 |

| · Orbit of the Moon, taking into account the Gravity of both the Earth and the Sun — §471 | 391 |

| · Prolate Spheroidal Fluid Figure — §491 | 409 |

| · The Earth's Equilibrium Shape — §492 | 410 |

| End of Book I, Chapter XI, § 494 | 413 |

Volume II

| Table of Principal Contents (5 pp.) | |

| Figure Plates (30 pp.) | |

| Book 1 (continued) | 1 |

| Chapter XII (Of the Methods of Infinitesimals …) — §§ 495-570 | 1 |

| · Centre of Gravity — §510 | 13 |

| · Of the Collision of Bodies — §511 | 14 |

| · Of the Descent of Bodies that Act upon One Another — §521 | 27 |

| · Of the Centre of Oscillation — §533 | 40 |

| · Of the Motion of Water Issuing from a Cylindric Vessel — §537 | 44 |

| · Of the Catenaria — §551 | 59 |

| · General Observations Concerning the Angles of Contact, etc. — §554 | 61 |

| · General Observations Concerning centripetal Forces, etc. — §563 | 67 |

| Chapter XIII (Determining the Lines of swiftest Descent in any Hypothesis of Gravity …) — §§ 571-608 | 74 |

| · When Gravity is Directed Towards a Given Centre — §578 | 80 |

| · Isoperimetrical Problems — §588 | 88 |

| · The Solid of Least Resistance — §606 | 100 |

| Chapter XIV (Of the Ellipse Considered as the Section of a Cylinder … Of the Figure of the Earth …) — §§ 609- | 101 |

| · Properties of the Ellipse — §609 | 101 |

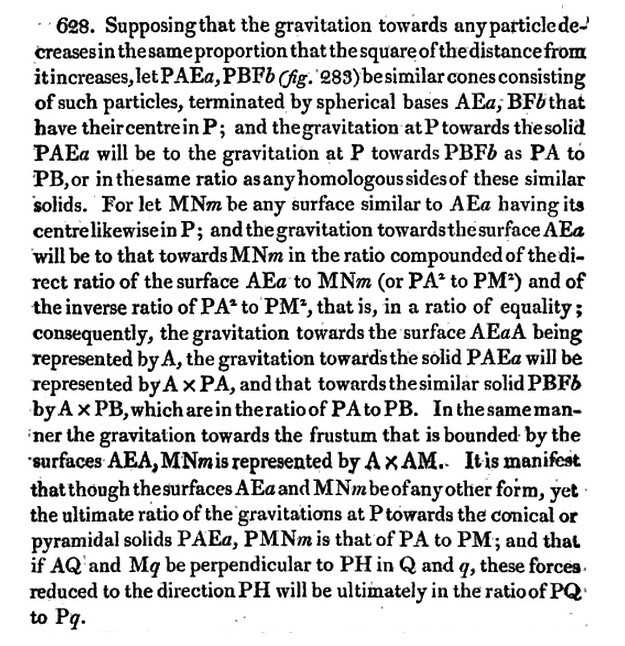

| · Of the Gravitation towards Spheres and Spheroids — §628 | 110 |

| · Of the Figures of Planets (including effects of rotation) — §636 | 116 |

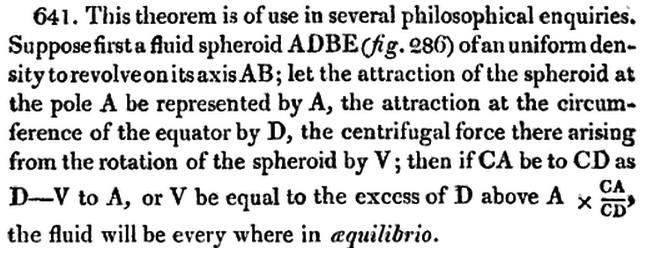

| · Key Concluding Theorem! — §641 | 119 |

| · Using geometric relations, illustrate how to quantitatively determine gravitational acceleration … | |

| [see related comment by Todhunter (1873), below] | |

| ▸ due to an arbitrarily shaped, uniform-density configuration — §642 | 120 |

| ▸ outside or on the surface of a uniform-density sphere — §643 | 121 |

| ▸ at the pole of an oblate spheroid — §644 | 122 |

| ▸ at the equator of an oblate spheroid — §645 | 123 |

| ▸ at both the pole and the equator of an oblong (i.e., prolate) spheroid — §647 | 125 |

| ▸ due to a pair of concentric, confocal spheroids — §648 | 127 |

| · Apply Specifically to the Earth — §661 | 136 |

| · What if the Earth's Density isn't Uniform but, instead, Varies Linearly with Distance? — §670 | 143 |

| · Jupiter — §682 | 152 |

| · Tides — §686 | 154 |

| · Concluding Paragraph — §696 | 161 |

| End of Book I | 162 |

Maclaurin's Discussion of Self-Gravitating, Oblate-Spheroidal Configurations

|

Paragraph (and related figure) extracted† from Colin Maclaurin (1742)

"A Treatise of Fluxions"

Volume II, Chapter XIV, §628 | |

|

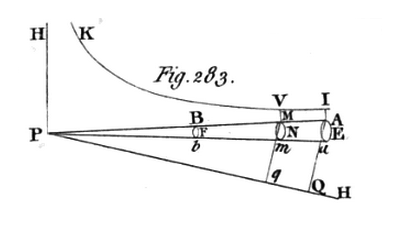

†As displayed here (left panel), this paragraph has been pieced together from two text segments found on separate but sequential pages (pp. 110-111) of Google's digitized volume. The diagram labeled Fig. 283 (top-right panel) has been extracted from Maclaurin's Figure Plate XXXIII, which appears near the beginning of the same digitized file, and has been displayed here without modification. The diagrams in the bottom-right panel have been reposted from Mathalino.com in an effort to illustrate what Maclaurin means by "frustum of a cone." |

|

|

Paragraph (and a pair of related diagrams) extracted† from Colin Maclaurin (1742)

"A Treatise of Fluxions"

Volume II, Chapter XIV, §630 | |

|

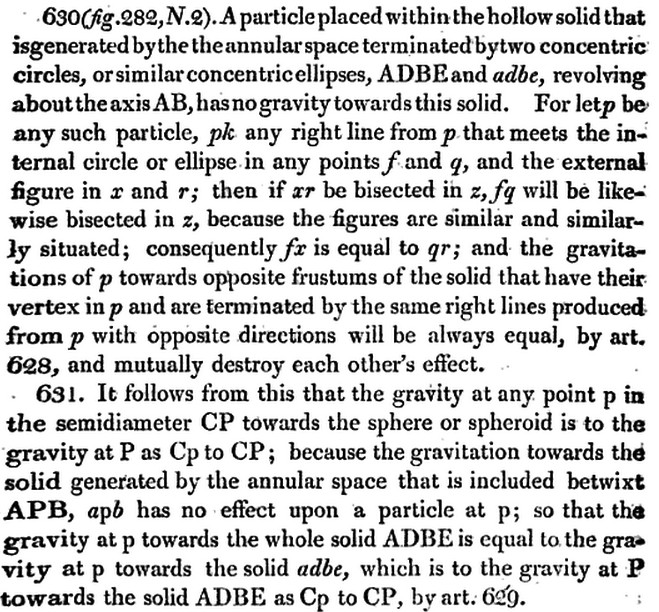

†The paragraph (left panel) has been extracted from p. 111 of Google's digitized volume and displayed here without modification. The pair of diagrams (right panel) has been extracted from Figure Plate XXXIII, which appears near the beginning of the same digitized file. Note that the diagram on the right has been (poorly) pieced together from segments that appear on two separate pages of Google's digitized volume, presumably because the figure plate, itself, is folded in the original print publication. |

|

Interpreting Maclaurin's Key Concluding Theorem

As noted above, in line with the table of contents for Volume II, the key theorem resulting from Maclaurin's analysis is …

Here we assess this geometrically formulated statement using today's more common differential operators and algebraic expressions. In particular, we draw from the discussion of Maclaurin spheroids that has been presented in an accompanying chapter of this H_Book.

CA: This is the semi-minor (polar) axis of the spheroid, which we have called, <math>~a_3</math>.

CD: This is the semi-major (equatorial) radius of the spheroid, which we have called, <math>~a_1</math>.

With both <math>~a_1</math> and <math>~a_3</math> specified, the eccentricity of the oblate spheroid is also known via the expression,

<math>

e^2 \equiv 1 - \biggl(\frac{a_3}{a_1}\biggr)^2 .

</math>

Attraction of the Spheroid at the Pole: We interpret this phrase to mean the magnitude of the acceleration (force per unit mass) due to gravity at the pole, which is,

|

<math>~\mathcal{A} \equiv \biggl|- \frac{\partial \Phi}{\partial z}\biggr|_\mathrm{pole}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\pi G \rho \biggl| \frac{\partial }{\partial z} \biggl[ I_\mathrm{BT} a_1^2 - \biggl(A_1 \varpi^2 + A_3 z^2 \biggr) \biggr]\biggr|_\mathrm{pole} </math> |

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ 2\pi G \rho A_3 a_3 \, . </math> |

Attraction at the Circumference of the Equator: We interpret this phrase to mean the magnitude of the acceleration (force per unit mass) due to gravity in the equatorial plane, at the surface of the configuration, which is,

|

<math>~\mathcal{D} \equiv \biggl|- \frac{\partial \Phi}{\partial \varpi}\biggr|_\mathrm{eq}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ \pi G \rho \biggl| \frac{\partial }{\partial \varpi} \biggl[ I_\mathrm{BT} a_1^2 - \biggl(A_1 \varpi^2 + A_3 z^2 \biggr) \biggr]\biggr|_\mathrm{eq} </math> |

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ 2\pi G \rho A_1 a_1 \, . </math> |

Centrifugal force in the equatorial plane arising from rotation: We interpret this phrase to mean the centrifugal acceleration (force per unit mass) given by the expression,

|

<math>~\mathcal{V} \equiv \frac{(\varpi \omega_0)^2}{\varpi}\biggr|_\mathrm{eq}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~a_1\omega_0^2 \, .</math> |

Maclaurin's theorem states that the rotating spheroidal configuration will be in equilibrium if,

|

<math>~\frac{\mathcal{D} - \mathcal{V}}{\mathcal{A}}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{a_3}{a_1} \, ,</math> |

or, equivalently,

|

<math>~\mathcal{D}-\mathcal{V}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\mathcal{A}\biggl( \frac{a_3}{a_1} \biggr) \, .</math> |

We choose to rewrite this expression and label it as,

Maclaurin's Theorem

<math>~\frac{\mathcal{V}}{a_1} = \frac{1}{a_1}\biggl[\mathcal{D} - \mathcal{A}\biggl( \frac{a_3}{a_1} \biggr)\biggr] </math>

which, in our terminology, becomes

|

<math>~\omega_0^2</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2\pi G \rho \biggl[ A_1 - A_3\biggl( \frac{a_3}{a_1} \biggr)^2 \biggr] </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2\pi G \rho \biggl[A_1 - A_3(1-e^2) \biggr] \, .</math> |

This is precisely the equilibrium frequency that we have derived elsewhere, from an evaluation of the gravitational potential of uniform-density spheroids.

Prolate Spheroid

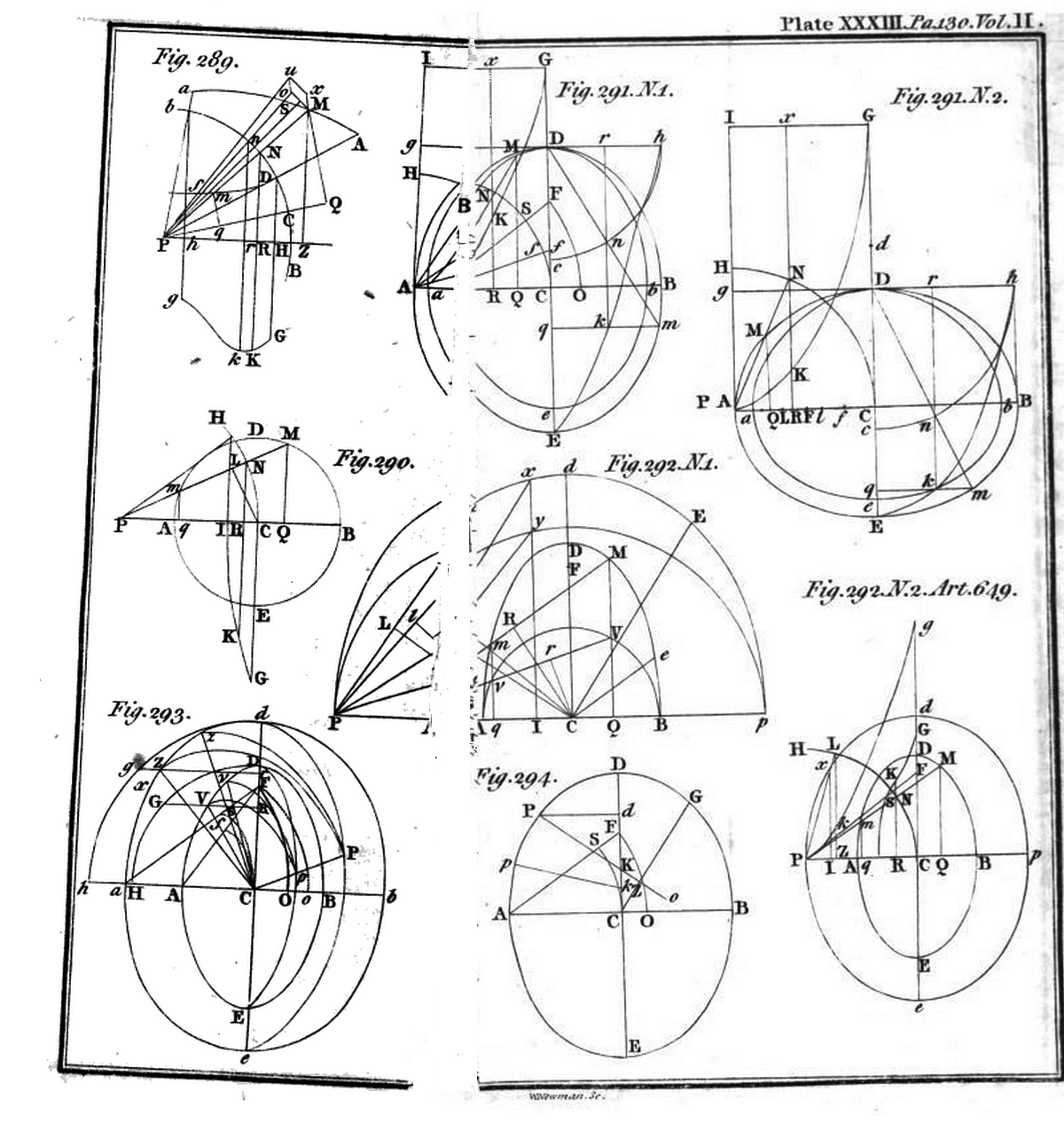

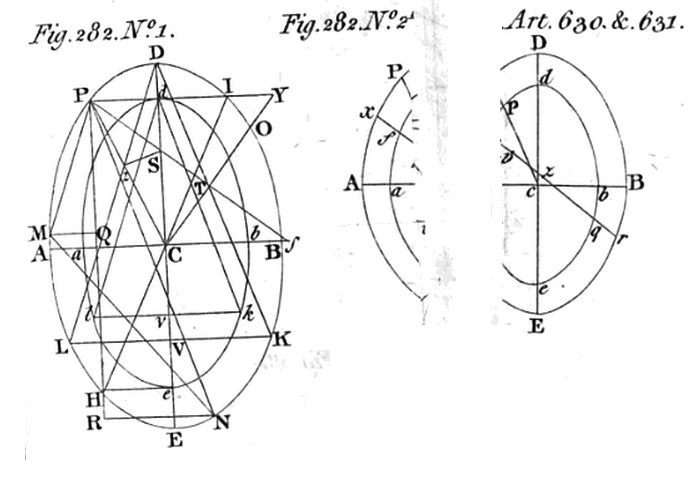

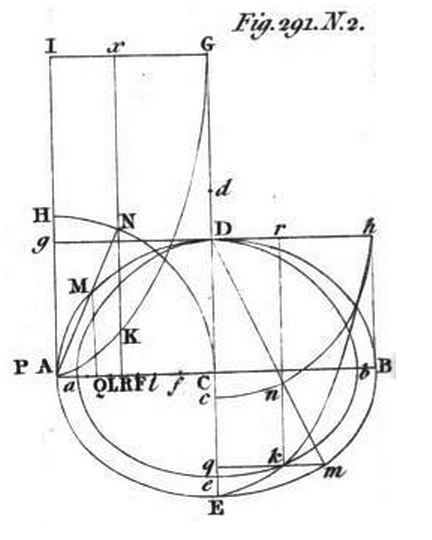

As one specific example, Maclaurin discusses the gravitational attraction at the pole of a uniform-density, prolate spheroid in his §647 of Volume II (pp. 125-127). While his discussion of this topic necessarily refers back to earlier sections — most importantly, §643 (spheres) and §644 (oblate spheroids) — it frequently refers to Figure 291, No. 2, which we have reproduced in the following figure.

|

Figure extracted† from Colin Maclaurin (1742)

"A Treatise of Fluxions"

Volume II, Figure Plate XXXIII | |

|

†The . |

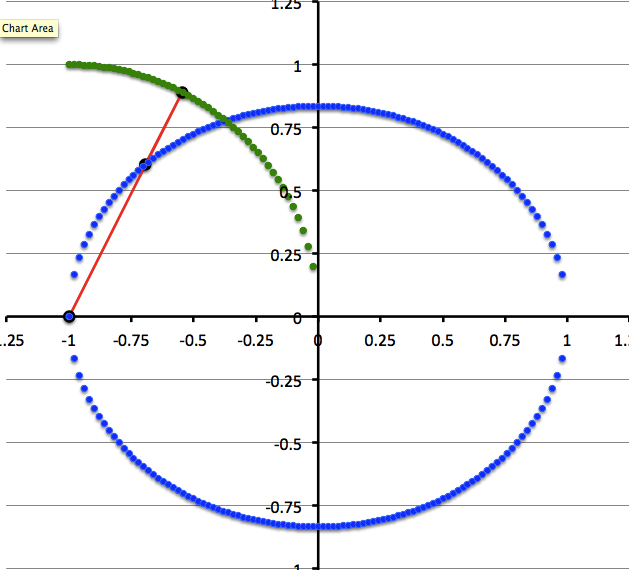

In this plot, the ellipse has an eccentricity, <math>~e = 0.55</math>, and the red line-segment has been drawn at an angle of <math>~\alpha = 0.7 (\tfrac{\pi}{2})</math>. |

While trying to decipher Maclaurin's geometrically based derivation, we have found it useful to re-draw key elements of this figure, deriving relevant algebraic or trigonometric relations along the way. Because the "oblong" ellipse in Maclaurin's figure is oriented such that the axis of revolution — the symmetry axis — is horizontal, and because we prefer to associate the <math>~z</math> axis with the symmetry axis of the configuration, we will rather unconventionally refer to the horizontal axis as the <math>~z</math> (symmetry) axis. Adopting a cylindrical coordinate system furthermore means that, in our notation, the vertical axis will be the <math>~\varpi</math> axis.

The blue ellipse centered on the origin of our plot represents Maclaurin's "ADBE" ellipse; in the expressions that follow, we will use <math>~a_1</math> and <math>~a_3</math> to refer, respectively, to the length of the semi-major axis (Maclaurin's line-segment "CA") and semi-minor axis (Maclaurin's line-segment "CD") of the ellipse; and, following Maclaurin, we will refer to leftmost point on the ellipse (Maclaurin's point "A") as the "pole" which is positioned at coordinate <math>~(z, \varpi) = (-a_1, 0)</math>. (Note that in our plot, we have set <math>~a_1 = 1</math>, but otherwise we will leave its specification arbitrary.) In our plot, Maclaurin's "CNH" circle is represented by the green quarter circle centered on the pole. The blue ellipse is defined by the relation,

|

<math>~\frac{z^2}{a_1^2} + \frac{\varpi^2}{a_3^2}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~1 </math> |

|

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~~ \frac{z^2}{a_1^2} + (1-e^2)^{-1}\frac{\varpi^2}{a_1^2}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~1 \, ,</math> |

and the green quarter circle is defined by the relation,

|

<math>~(a_1 + z)^2 + \varpi^2</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~a_1^2 </math> |

|

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~~ \biggl(1 + \frac{z}{a_1} \biggr)^2 + \frac{\varpi^2}{a_1^2}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~1 \, .</math> |

The red line-segment in our plot is what Maclaurin refers to as "AM," which is any right line from the pole A. We will use the variable, <math>~\alpha</math>, to identify the angle between this line-segment and the horizontal axis; in determining the gravitational attraction at pole A, Maclaurin ultimately sweeps this angle through the range, <math>~0 \le \alpha \le \tfrac{\pi}{2}</math>. Points lying along this line are defined by the relation,

|

<math>~\varpi</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~(a_1+z)\tan\alpha</math> |

|

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~~ \frac{\varpi}{a_1}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl(1+\frac{z}{a_1}\biggr)\tan\alpha \, .</math> |

Intersection With Circle

Hence, the red line-segment intersects the green quarter-circle when,

|

<math>~1- \biggl(1 + \frac{z}{a_1} \biggr)^2</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl(1+\frac{z}{a_1}\biggr)^2\tan^2\alpha </math> |

|

<math>~\Rightarrow~~~~\biggl(1+\frac{z}{a_1}\biggr)^2(1+\tan^2\alpha)</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~1 </math> |

|

<math>~\Rightarrow~~~~\frac{z}{a_1}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~(1+\tan^2\alpha)^{-1/2} -1 </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\cos\alpha -1 \, .</math> |

Correspondingly,

<math>\frac{\varpi}{a_1} = (\cos\alpha)\tan\alpha = \sin\alpha \, .</math>

Intersection With Ellipse

Similarly, the red line-segment intersects the blue ellipse when,

|

<math>~(1-e^2)\biggl[1- \biggl(\frac{z}{a_1} \biggr)^2\biggr]</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl(1+\frac{z}{a_1}\biggr)^2\tan^2\alpha </math> |

|

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~~ (1-e^2) - (1-e^2)\biggl(\frac{z}{a_1} \biggr)^2</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl[1+2\biggl(\frac{z}{a_1}\biggr)+\biggl(\frac{z}{a_1}\biggr)^2\biggr]\tan^2\alpha </math> |

|

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~~ 0</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl[\tan^2\alpha - (1-e^2)\biggr]+2\biggl(\frac{z}{a_1}\biggr)\tan^2\alpha +\biggl(\frac{z}{a_1}\biggr)^2\biggl[\tan^2\alpha+ (1-e^2) \biggr] \, .</math> |

The roots of this quadratic equation are,

|

<math>~\frac{z}{a_1}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{b}{2a}\biggl\{ -1 \pm \biggl[ 1 - \frac{4ac}{b^2} \biggr]^{1/2} \biggr\}</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{\tan^2\alpha}{(\tan^2\alpha+ 1-e^2 )}\biggl\{ -1 \pm \biggl[ 1 - \frac{[\tan^2\alpha - (1-e^2)][ \tan^2\alpha+ (1-e^2) ]}{\tan^4\alpha} \biggr]^{1/2} \biggr\}</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{\tan^2\alpha}{(\tan^2\alpha+ 1-e^2 )}\biggl\{ -1 \pm \frac{1}{\tan^2\alpha}\biggl[ \tan^4\alpha - [\tan^4\alpha - (1-e^2)^2] \biggr]^{1/2} \biggr\}</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~-~\frac{[\tan^2\alpha \mp (1-e^2) ]}{[\tan^2\alpha+ (1-e^2 )]} \, .</math> |

The "inferior" root gives,

<math>~\frac{z}{a_1}\biggr|_- = -1 \, ,</math>

while the "superior" root gives,

|

<math>~\frac{z}{a_1}\biggr|_+</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~- ~\frac{[\tan^2\alpha - (1-e^2) ]}{[\tan^2\alpha+ (1-e^2) ]} \, .</math> |

Correspondingly,

<math>\frac{\varpi}{a_1}\biggr|_- = 0 \, ,</math>

and,

<math>\frac{\varpi}{a_1}\biggr|_+ = \tan\alpha\biggl\{ 1 - ~\frac{[\tan^2\alpha - (1-e^2) ]}{[\tan^2\alpha+ (1-e^2) ]} \biggr\} \, .</math>

The "inferior" root clearly identifies the intersection of the red line-segment with the pole of the prolate spheroid. The "superior" root identifies the point at which the red line-segment intersects and crosses the blue ellipse, below the pole.

Generate Curve AKG

In §644 (p. 122 of Volume II) of his Treatise, Maclaurin states that "the gravity at the pole A towards the spheroid ADBE will be measured by [the ratio],"

<math>\mathcal{A} = \frac{\mathrm{AKGC}}{AC} \, ,</math>

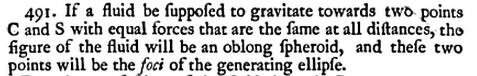

where the numerator, "AKGC," is the area under the curve, "AKG," and the denominator is the length of the semi-major axis, <math>~a_1</math>. So a key element of Maclaurin's derivation is the proper construction of the curve, "AKG." The key sentence from his §644 appears to be the following:

We interpret this phrase to mean that, as the angle, <math>~\alpha</math>, varies from <math>~\tfrac{\pi}{2}</math> to <math>~0</math>, the curve "AKG" is generated by plotting, as the ordinate, the length of the line-segment "AQ" and, as the abscissa, the <math>~z</math>-coordinate location of the vertical line, "RN" — we'll label this, <math>~z_\mathrm{RN}</math>. In our terminology, as derived above, <math>~z_\mathrm{RN}</math> is the <math>~z</math>-coordinate of the intersection of the red line-segment with the green quarter-circle, that is,

|

<math>~z_\mathrm{RN}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\cos\alpha - 1 \, .</math> |

And the magnitude of "AQ" is obtained from the <math>~z</math>-coordinate location of the vertical line, "MQ" — that is, the <math>~z</math>-coordinate of the intersection of the red line-segment with the blue ellipse — as derived above. Specifically, we interpret Maclaurin's phrase to mean that,

|

<math>~\frac{\mathrm{AQ}}{a_1} \equiv 1 + \frac{z}{a_1}\biggr|_+</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~1 - ~\frac{[\tan^2\alpha - (1-e^2) ]}{[\tan^2\alpha+ (1-e^2) ]} \, .</math> |

Using the first of these two expressions, we can rewrite the tangent function directly in terms of the ordinate, <math>~z_\mathrm{RN}</math>; specifically,

<math>\tan^2\alpha = \frac{1- \cos^2\alpha}{\cos^2\alpha} = \frac{1- (1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2}{(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2} \, .</math>

Hence,

|

<math>~\frac{\mathrm{AQ}}{a_1} </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~1 - ~\frac{(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2[\tan^2\alpha - (1-e^2) ]}{(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2[\tan^2\alpha+ (1-e^2) ]}</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~1 - ~\frac{[1-(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2 - (1-e^2)(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2 ]}{[1-(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2+ (1-e^2) (1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2]}</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~1 - ~\frac{[1+(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2 (-1 - (1-e^2) ]}{[1+(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2(-1+1-e^2)]}</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~1 - ~\frac{[1-(2-e^2)(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2 ]}{[1-e^2(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2]}</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{[1-e^2(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2]-[1-(2-e^2)(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2 ]}{[1-e^2(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2]}</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{[2(1-e^2)(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2 ]}{[1-e^2(1+z_\mathrm{RN})^2]} \, .</math> |

In our above figure, this function, <math>~\mathrm{AQ}(z_\mathrm{RN})</math> normalized to <math>~a_1</math>, is delineated by the orange triangles over the coordinate range, <math>~-1 \le z_\mathrm{RN} \le 0</math>. If our interpretation of Maclaurin's discussion is correct, this is precisely the curve in Maclauin's Figure 291, No. 2 that is labeled, "AKG." The area, "AKGC" — which, according to Maclaurin, gives the gravitational acceleration at the pole A — can be determined by carrying out the integral,

|

<math>~\mathcal{A} = \frac{\mathrm{AKGC}}{a_1} </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\int_{-1}^0 \biggl[\frac{\mathrm{AQ}}{a_1}\biggr]dz_\mathrm{RN} \, .</math> |

This integral can be more cleanly evaluated if we make the variable substitution,

<math>u_\mathrm{RN} \equiv 1 + z_\mathrm{RN} \, ,</math>

with a corresponding shift in the limits of integration from <math>~(-1 \rightarrow 0)</math>, for <math>~z_\mathrm{RN}</math>, to <math>~(0 \rightarrow 1)</math>, for <math>~u_\mathrm{RN}</math>. Specifically, we find,

|

<math>~\mathcal{A} </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~2(1-e^2) \int_{0}^1 \frac{u_\mathrm{RN}^2 }{1-e^2 u_\mathrm{RN}^2} ~du_\mathrm{RN}</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~-2(1-e^2) \biggl[ \frac{u_\mathrm{RN}}{e^2} \biggr]_{0}^1 + \frac{1}{e^4} \int_{0}^1 \frac{du_\mathrm{RN}}{e^{-2}- u_\mathrm{RN}^2} </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~-\frac{2(1-e^2)}{e^2} + \frac{2(1-e^2)}{e^4} \biggl\{ \frac{e}{2} \ln \biggl[ \frac{e^{-2} +u_\mathrm{RN} }{e^{-2} -u_\mathrm{RN} } \biggr] \biggr\}_{0}^1 </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~-\frac{2(1-e^2)}{e^2} + \frac{(1-e^2)}{e^3} \ln \biggl[ \frac{1 + e^{2} }{1-e^{2}} \biggr] \, .</math> |

This is precisely the result obtained earlier.

Related Discussions

- Our derivation of the properties of Maclaurin Spheriods

- Wikipedia's documentation of Colin Maclaurin

- Chandrasekhar's (1967) historical account

- Notes on the Life and Works of colin Maclaurin by Charles Tweedie (1919)

- I. Todhunter (1873), A History of the Mathematical Theories of Attraction and the Figure of the Earth, from the time of Newton to that of Laplace. Note that Todhunter's discussion of Maclaurin's contributions can be found in Chapter IX, pp. 133-175.

|

|---|

|

© 2014 - 2021 by Joel E. Tohline |