Difference between revisions of "User:Tohline/Appendix/Ramblings/PPTori"

(→Cubic Equation Solution: Begin working through Wolfram's cubic equation solution) |

|||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="right"> | <td align="right"> | ||

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~~ | <math>~\Rightarrow ~~~~ x^3 \pm \tfrac{1}{2}x^2 \mp \tfrac{1}{2}(\beta\eta)^2</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Following [http://mathworld.wolfram.com/CubicFormula.html Wolfram's discussion of the cubic formula], we should view this expression as a specific case of the general formula, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>~x^3 + a_2x^2 + a_1x + a_0 = 0 \, .</math> | |||

</div> | |||

Doing this — and focusing, first, on the ''superior'' sign convention — we see that the coefficients that lead to our specific cubic equation are: | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~a_2</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\tfrac{1}{2} \, ,</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~a_1</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~0 \, ,</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~a_0</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~- \tfrac{1}{2}(\beta\eta)^2 \, .</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

As is detailed in equations (54) - (56) of [http://mathworld.wolfram.com/CubicFormula.html Wolfram's discussion of the cubic formula], the three roots of any cubic equation are: | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~x_1</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~ | |||

-\frac{1}{3}a_2 + (S + T) \, , | |||

</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~x_2</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~ | |||

-\frac{1}{3}a_2 - \frac{1}{2} (S + T) + \frac{1}{2} \it{i} \sqrt{3} (S-T)\, , | |||

</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~x_3</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~ | |||

-\frac{1}{3}a_2 - \frac{1}{2} (S + T) - \frac{1}{2} \it{i} \sqrt{3} (S-T)\, , | |||

</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

where, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~S</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~\equiv</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~[R + \sqrt{D}]^{1/3} \, ,</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~T</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~\equiv</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~[R - \sqrt{D}]^{1/3} \, ,</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~D</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~\equiv</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~Q^3 + R^2 \, .</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

Applying Wolfram's definitions of the <math>~Q</math> and <math>~R</math> parameters to our particular problem gives, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~Q</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~\equiv</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\frac{3a_1 - a_2^2}{3^2} = -\biggl(\frac{a_2}{3}\biggr)^2 = - \frac{1}{2^2\cdot 3^2} \, ;</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~R</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~\equiv</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\frac{3^2a_2 a_1 - 3^3a_0 - 2a_2^3}{2\cdot 3^3} | |||

= - \frac{1}{2\cdot 3^3} \biggl[ -\frac{3^3}{2}(\beta\eta)^2 + \frac{1}{2^2} \biggr] </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~ | |||

- \frac{1}{2^3\cdot 3^3} \biggl[ 1-2\cdot 3^3(\beta\eta)^2 \biggr]\, . </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

Hence, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~2^6\cdot 3^6D</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~[ 1-2\cdot 3^3(\beta\eta)^2 ]^2-1 \, ;</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~2\cdot 3S</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~[2^3\cdot 3^3R + \sqrt{2^6\cdot 3^6D}]^{1/3} </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\biggl\{ \sqrt{[ 1-2\cdot 3^3(\beta\eta)^2 ]^2-1} | |||

+ \biggl[ 2\cdot 3^3(\beta\eta)^2 -1\biggr] \biggr\}^{1/3} </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

<!-- COMMENT OUT DEVELOPMENT FROM VANDERBILT NOTES ... | |||

Following [http://www.math.vanderbilt.edu/~schectex/courses/cubic/ the online Vanderbilt notes], we should view this expression as a specific case of the general formula, | Following [http://www.math.vanderbilt.edu/~schectex/courses/cubic/ the online Vanderbilt notes], we should view this expression as a specific case of the general formula, | ||

| Line 299: | Line 527: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

On the other hand, when <math>~\eta = 1</math> (''i.e.,'' at the surface of the torus), we see that <math>~Q = 1 - | On the other hand, when <math>~\eta = 1</math> (''i.e.,'' at the surface of the torus), we see that <math>~Q = 1 - 2\cdot 3^3\beta^2</math>, in which case, | ||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>~Q^2 -1 = 2^2\cdot 3^6\beta^4 - 2^2\cdot 3^3\beta^2 = 2^2\cdot 3^3\beta^2 (3^3\beta^2 -1) \, ,</math> | |||

</div> | |||

and, | |||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

| Line 313: | Line 546: | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math>~ | <math>~ | ||

[Q + (Q^2 - 1)^{1/2} ]^{1/3} + [Q - (Q^2 - 1)^{1/2} ]^{1/3} \mp 1 | [Q + (Q^2 - 1)^{1/2} ]^{1/3} + [Q - (Q^2 - 1)^{1/2} ]^{1/3} \mp 1 | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

| Line 320: | Line 553: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

END COMMENTS ON VANDERBILT NOTES --!> | |||

===Analytically Prescribed Eigenvector=== | ===Analytically Prescribed Eigenvector=== | ||

Revision as of 22:36, 19 February 2016

Stability Analyses of PP Tori

|

|---|

| | Tiled Menu | Tables of Content | Banner Video | Tohline Home Page | |

As has been summarized in an accompanying chapter — also see our related detailed notes — we have been trying to understand why unstable nonaxisymmetric eigenvectors have the shapes that they do in rotating toroidal configurations. For any azimuthal mode, <math>~m</math>, we are referring both to the radial dependence of the distortion amplitude, <math>~f_m(\varpi)</math>, and the radial dependence of the phase function, <math>~\phi_m(\varpi)</math> — the latter is what the Imamura and Hadley collaboration refer to as a "constant phase locus." Some old videos showing the development over time of various self-gravitating "constant phase loci" can be found here; these videos supplement the published work of Woodward, Tohline & Hachisu (1994).

Here, we focus specifically on instabilities that arise in so-called (non-self-gravitating) Papaloizou-Pringle tori and will draw heavily from two publications: (1) Papaloizou & Pringle (1987), MNRAS, 225, 267 — The dynamical stability of differentially rotating discs. III. — hereafter, PPIII — and (2) Blaes (1985), MNRAS, 216, 553 — Oscillations of slender tori.

PP III

|

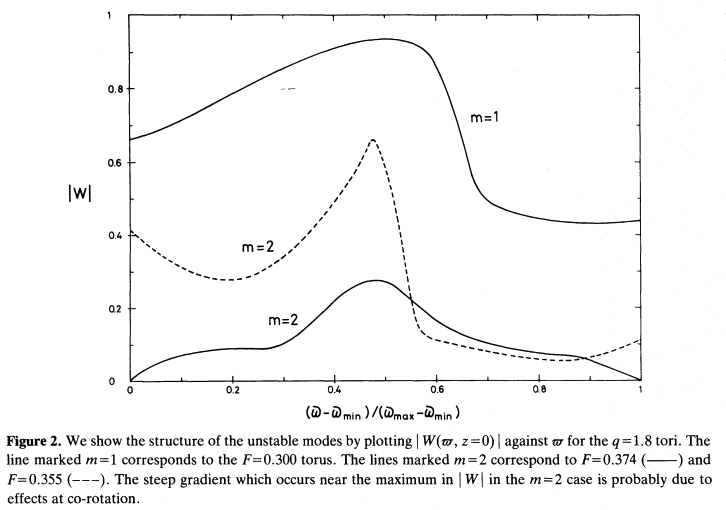

Figure 2 extracted without modification from p. 274 of J. C. B. Papaloizou & J. E. Pringle (1987)

"The Dynamical Stability of Differentially Rotating Discs. III"

MNRAS, vol. 225, pp. 267-283 © The Royal Astronomical Society |

Blaes85

His Notation

Blaes (1985) adopts a polytropic equation of state,

<math>~\frac{\rho}{\rho_c} = \Theta_H^n \, ,</math>

which gives rise to (slim tori) equilibrium structures for which (see his equation 1.3),

|

<math>~\Theta_H</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~1 - \frac{1}{\beta^2}\biggl[x^2 + x^3(3\cos\theta - \cos^3\theta) + \mathcal{O}(x^4) \biggr] \, ,</math> |

where, the (constant) model parameter,

<math>\beta \equiv \frac{(2n)^{1/2}}{\mathcal{M}_0} \, ,</math>

and <math>~\mathcal{M}_0</math> is the Mach number of the rotational velocity at the torus center. Blaes then adopts a related parameter that is constant on isobaric surfaces, namely,

<math>\eta^2 \equiv 1 - \Theta_H \, ,</math>

which is unity at the surface of the torus and which goes to zero at the cross-sectional center of the torus. Notice that <math>~\eta</math> tracks the "radial" coordinate that measures the distance from the center of the torus; in particular, keeping only the leading-order term in <math>~x</math>, there is a simple linear relationship between <math>~\eta</math> and <math>~x</math>, namely,

|

<math>~\eta</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~[1 - \Theta_H]^{1/2} \approx \frac{x}{\beta} \, .</math> |

Cubic Equation Solution

For later use, let's invert the cubic relation to obtain a more broadly applicable <math>~x(\eta)</math> function. Because we are only interested in radial profiles in the equatorial plane — that is, only for the values of <math>~\theta = 0</math> or <math>~\theta=\pi</math> — the relation to be inverted is,

|

<math>~x^2 \pm 2 x^3</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~(\beta\eta)^2</math> |

|

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~~ x^3 \pm \tfrac{1}{2}x^2 \mp \tfrac{1}{2}(\beta\eta)^2</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~0 \, .</math> |

Following Wolfram's discussion of the cubic formula, we should view this expression as a specific case of the general formula,

<math>~x^3 + a_2x^2 + a_1x + a_0 = 0 \, .</math>

Doing this — and focusing, first, on the superior sign convention — we see that the coefficients that lead to our specific cubic equation are:

|

<math>~a_2</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\tfrac{1}{2} \, ,</math> |

|

<math>~a_1</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~0 \, ,</math> |

|

<math>~a_0</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~- \tfrac{1}{2}(\beta\eta)^2 \, .</math> |

As is detailed in equations (54) - (56) of Wolfram's discussion of the cubic formula, the three roots of any cubic equation are:

|

<math>~x_1</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ -\frac{1}{3}a_2 + (S + T) \, , </math> |

|

<math>~x_2</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ -\frac{1}{3}a_2 - \frac{1}{2} (S + T) + \frac{1}{2} \it{i} \sqrt{3} (S-T)\, , </math> |

|

<math>~x_3</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ -\frac{1}{3}a_2 - \frac{1}{2} (S + T) - \frac{1}{2} \it{i} \sqrt{3} (S-T)\, , </math> |

where,

|

<math>~S</math> |

<math>~\equiv</math> |

<math>~[R + \sqrt{D}]^{1/3} \, ,</math> |

|

<math>~T</math> |

<math>~\equiv</math> |

<math>~[R - \sqrt{D}]^{1/3} \, ,</math> |

|

<math>~D</math> |

<math>~\equiv</math> |

<math>~Q^3 + R^2 \, .</math> |

Applying Wolfram's definitions of the <math>~Q</math> and <math>~R</math> parameters to our particular problem gives,

|

<math>~Q</math> |

<math>~\equiv</math> |

<math>~\frac{3a_1 - a_2^2}{3^2} = -\biggl(\frac{a_2}{3}\biggr)^2 = - \frac{1}{2^2\cdot 3^2} \, ;</math> |

|

<math>~R</math> |

<math>~\equiv</math> |

<math>~\frac{3^2a_2 a_1 - 3^3a_0 - 2a_2^3}{2\cdot 3^3} = - \frac{1}{2\cdot 3^3} \biggl[ -\frac{3^3}{2}(\beta\eta)^2 + \frac{1}{2^2} \biggr] </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ - \frac{1}{2^3\cdot 3^3} \biggl[ 1-2\cdot 3^3(\beta\eta)^2 \biggr]\, . </math> |

Hence,

|

<math>~2^6\cdot 3^6D</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~[ 1-2\cdot 3^3(\beta\eta)^2 ]^2-1 \, ;</math> |

|

<math>~2\cdot 3S</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~[2^3\cdot 3^3R + \sqrt{2^6\cdot 3^6D}]^{1/3} </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl\{ \sqrt{[ 1-2\cdot 3^3(\beta\eta)^2 ]^2-1} + \biggl[ 2\cdot 3^3(\beta\eta)^2 -1\biggr] \biggr\}^{1/3} </math> |