Difference between revisions of "User:Tohline/Apps/MaclaurinSpheroids"

(→Maclaurin Spheroids (axisymmetric structure): better link to Maclaurin (1742)) |

|||

| (27 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__FORCETOC__ | __FORCETOC__ | ||

<!-- __NOTOC__ will force TOC off --> | <!-- __NOTOC__ will force TOC off --> | ||

=Maclaurin Spheroids (axisymmetric structure)= | =Maclaurin Spheroids (axisymmetric structure)= | ||

{{LSU_HBook_header}} | |||

<!-- [[Image:LSU_Structure_still.gif|74px|left]] --> | <!-- [[Image:LSU_Structure_still.gif|74px|left]] --> | ||

There is no particular reason why one should guess ahead of time that the equilibrium properties of ''any'' rotating, self-gravitating configuration should be describable in terms of analytic functions. As luck would have it, however, the gravitational potential at the surface of and inside an homogeneous spheroid is expressible analytically. (The potential is constant on concentric spheroidal surfaces that generally have a different axis ratio from the spheroidal mass distribution.) Furthermore, the gradient of the gravitational potential is separable in cylindrical coordinates, proving to be a simple ''linear'' function of both <math>\varpi</math> and <math>z</math>. | |||

There is no particular reason why one should guess ahead of time that the equilibrium properties of ''any'' rotating, self-gravitating configuration should be describable in terms of analytic functions. As luck would have it, however, the gravitational potential at the surface of and inside an homogeneous spheroid is expressible analytically. (The potential is constant on concentric spheroidal surfaces that generally have a different axis ratio from the spheroidal mass distribution.) Furthermore, the gradient of the gravitational potential is separable in cylindrical coordinates, proving to be a simple ''linear'' function of both <math>\varpi</math> and <math>~z</math>. | |||

If the spheroid is uniformly rotating, this behavior conspires nicely with the behavior of the [[User:Tohline/PGE/RotatingFrame#Centrifugal_and_Coriolis_Accelerations|centrifugal acceleration]] — which also will be a linear function of <math>\varpi</math> — to permit an analytic (and integrable) prescription of the pressure gradient. Not surprisingly, it resembles the functional form of the pressure gradient that is required to balance the gravitational force in [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/UniformDensity|uniform-density spheres]]. | If the spheroid is uniformly rotating, this behavior conspires nicely with the behavior of the [[User:Tohline/PGE/RotatingFrame#Centrifugal_and_Coriolis_Accelerations|centrifugal acceleration]] — which also will be a linear function of <math>\varpi</math> — to permit an analytic (and integrable) prescription of the pressure gradient. Not surprisingly, it resembles the functional form of the pressure gradient that is required to balance the gravitational force in [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/UniformDensity|uniform-density spheres]]. | ||

As a consequence of this good fortune, the equilibrium structure of a uniformly rotating, uniform-density (n = 0), axisymmetric configuration can be shown to be precisely an oblate spheroid whose internal properties are describable in terms of analytic expressions. | As a consequence of this good fortune, the equilibrium structure of a uniformly rotating, uniform-density <math>~(n = 0)</math>, axisymmetric configuration can be shown to be precisely an oblate spheroid whose internal properties are describable in terms of analytic expressions. As we show [[User:Tohline/Apps/MaclaurinSpheroids/GoogleBooks#Interpreting_Maclaurin.27s_Key_Concluding_Theorem|in an accompanying discussion]], the angular velocity that is required to keep a self-gravitating spheroid of a specified eccentricity in equilibrium can be obtained from a theorem — we will refer to it as [[User:Tohline/Apps/MaclaurinSpheroids/GoogleBooks#MaclaurinTheorem|Maclaurin's Theorem]] — that was derived from purely geometric arguments over 270 years ago by Colin Maclaurin (1742) in ''A Treatise of Fluxions.'' This result has been enumerated in many subsequent publications (e.g., Tassoul 1978; Chandrasekhar 1987). It should be appreciated that both [https://books.google.com/books?id=dCAOAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false Volume I] and [https://books.google.com/books?id=xfQ7AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false Volume II] of Maclaurin's (1742) ''Treatise'' can now be accessed online via Google Books. Selected excerpts from these two volumes are shown [[User:Tohline/Apps/MaclaurinSpheroids/GoogleBooks#Excerpts_from_A_Treatise_of_Fluxions|in our accompanying discussion]]. | ||

==Properties of Uniform-Density Spheroids== | ==Properties of Uniform-Density Spheroids== | ||

===Surface Definition=== | ===Surface Definition=== | ||

Let <math>a_1</math> be the equatorial radius and <math>a_3</math> the polar radius of a uniform-density object whose surface is defined precisely by an oblate spheroid. The degree of flattening of the object may be parameterized in terms of the axis ratio <math>a_3/a_1</math>, or in terms of the object's eccentricity, | Let <math>~a_1</math> be the equatorial radius and <math>~a_3</math> the polar radius of a uniform-density object whose surface is defined precisely by an oblate spheroid. The degree of flattening of the object may be parameterized in terms of the axis ratio <math>~a_3/a_1</math>, or in terms of the object's eccentricity, | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

| Line 22: | Line 23: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

(For an ''oblate'' spheroid, <math>a_3 \leq a_1</math>; hence, the eccentricity is restricted to the range <math>0 \leq e \leq 1</math>.) The meridional cross-section of such a spheroid is an ellipse with the same eccentricity. The foci of this ellipse lie in the equatorial plane of the spheroid at a distance <math>\varpi = ea_1</math> from the minor | (For an ''oblate'' spheroid, <math>~a_3 \leq a_1</math>; hence, the eccentricity is restricted to the range <math>~0 \leq e \leq 1</math>.) The meridional cross-section of such a spheroid is an ellipse with the same eccentricity. The foci of this ellipse lie in the equatorial plane of the spheroid at a distance <math>~\varpi = ea_1</math> from the minor <math>~(z)</math> axis. | ||

===Mean Radius=== | ===Mean Radius=== | ||

| Line 29: | Line 30: | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

~a_\mathrm{mean} \equiv \biggl[a_1^2 a_3 \biggr]^{1/3} = a_1 (1 - e^2)^{1/6} , | |||

</math> | </math> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

which is equivalent to the radius of a sphere in the limit <math>a_3 = a_1</math> | which is equivalent to the radius of a sphere in the limit <math>~a_3 = a_1</math> <math>~(e=0)</math>. | ||

===Mass=== | ===Mass=== | ||

| Line 44: | Line 45: | ||

===Gravitational Potential=== | ===Gravitational Potential=== | ||

In an accompanying discussion entitled, ''[[User:Tohline/ThreeDimensionalConfigurations/HomogeneousEllipsoids#Properties_of_Homogeneous_Ellipsoids|Properties of Homogeneous Ellipsoids]]'', an expression is given for the gravitational potential <math>\Phi(\vec{x})</math> at an internal point or on the surface of an homogeneous ellipsoid with semi-axes <math>(x,y,z) = (a_1,a_2,a_3)</math>. For an [[User:Tohline/ThreeDimensionalConfigurations/HomogeneousEllipsoids#oblate|homogeneous, oblate spheroid]] in which <math>a_1 = a_2 \geq a_3</math>, this analytic expression defining the potential reduces to the form, | In an accompanying discussion entitled, ''[[User:Tohline/ThreeDimensionalConfigurations/HomogeneousEllipsoids#Properties_of_Homogeneous_Ellipsoids|Properties of Homogeneous Ellipsoids]]'', an expression is given for the gravitational potential <math>\Phi(\vec{x})</math> at an internal point or on the surface of an homogeneous ellipsoid with semi-axes <math>~(x,y,z) = (a_1,a_2,a_3)</math>. For an [[User:Tohline/ThreeDimensionalConfigurations/HomogeneousEllipsoids#oblate|homogeneous, oblate spheroid]] in which <math>~a_1 = a_2 \geq a_3</math>, this analytic expression defining the potential reduces to the form, | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math> | <p><math> | ||

\Phi(\varpi,z) = -\pi G \rho \biggl[ I_\mathrm{BT} a_1^2 - \biggl(A_1 \varpi^2 + A_3 z^2 \biggr) \biggr], | \Phi(\varpi,z) = -\pi G \rho \biggl[ I_\mathrm{BT} a_1^2 - \biggl(A_1 \varpi^2 + A_3 z^2 \biggr) \biggr], | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</p> | |||

[<b>[[User:Tohline/Appendix/References#ST83|<font color="red">ST83</font>]]</b>], §7.3, p. 169, Eq. (7.3.1) | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

where, the coefficients <math>A_1</math>, <math>A_3</math>, and <math>I_\mathrm{BT}</math> are functions only of the spheroid's eccentricity. Specifically, | where, the coefficients <math>~A_1</math>, <math>~A_3</math>, and <math>~I_\mathrm{BT}</math> are functions only of the spheroid's eccentricity. Specifically, | ||

<table align="center" border=0 cellpadding="3"> | <table align="center" border=0 cellpadding="3"> | ||

| Line 58: | Line 61: | ||

<td align="right"> | <td align="right"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

A_1 | ~A_1 | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

= | ~= | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

\frac{1}{e^2} \biggl[\frac{\sin^{-1}e}{e} - (1-e^2)^{1/2} \biggr](1-e^2)^{1/2} | \frac{1}{e^2} \biggl[\frac{\sin^{-1}e}{e} - (1-e^2)^{1/2} \biggr](1-e^2)^{1/2} \, ; | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

| Line 75: | Line 78: | ||

<td align="right"> | <td align="right"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

A_3 | ~A_3 | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

= | ~= | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

\frac{2}{e^2} \biggl[(1-e^2)^{-1/2} -\frac{\sin^{-1}e}{e} \biggr](1-e^2)^{1/2} | \frac{2}{e^2} \biggl[(1-e^2)^{-1/2} -\frac{\sin^{-1}e}{e} \biggr](1-e^2)^{1/2} \, ; | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

| Line 92: | Line 95: | ||

<td align="right"> | <td align="right"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

I_\mathrm{BT} | ~I_\mathrm{BT} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

= | ~= | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

2A_1 + A_3(1-e^2) = 2 (1-e^2)^{1/2} \biggl[ \frac{\sin^{-1}e}{e}\biggr] | ~2A_1 + A_3(1-e^2) = 2 (1-e^2)^{1/2} \biggl[ \frac{\sin^{-1}e}{e}\biggr] \, . | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center" colspan="3"> | |||

[<b>[[User:Tohline/Appendix/References#ST83|<font color="red">ST83</font>]]</b>], §7.3, p. 170, Eqs. (7.3.8) | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

Note that these three expressions have the following values in the limit of a sphere <math>(e=0)</math> or in the limit of an infinitesimally thin disk <math>(e=1)</math>: | Note that these three expressions have the following values in the limit of a sphere <math>~(e=0)</math> or in the limit of an infinitesimally thin disk <math>~(e=1)</math>: | ||

<table align="center" border=1 cellpadding="3"> | <table align="center" border=1 cellpadding="3"> | ||

| Line 122: | Line 130: | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<b><math>e=0</math></b> | <b><math>~e=0</math></b> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<b><math>e=1</math></b> | <b><math>~e=1</math></b> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<b><math>A_1</math></b> | <b><math>~A_1</math></b> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

| Line 136: | Line 144: | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<math>0</math> | <math>~0</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<b><math>A_3</math></b> | <b><math>~A_3</math></b> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

| Line 147: | Line 155: | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<math>2</math> | <math>~2</math> | ||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<b><math>~I_\mathrm{BT}</math></b> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~2</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~0</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

====Example Equi-gravitational-potential Contours==== | |||

As an example, let's examine the gravitational potential everywhere inside (and on the surface) of the oblate spheroid whose properties are presented in the first row of model data in [[User:Tohline/ThreeDimensionalConfigurations/HomogeneousEllipsoids#Table1|Table 1 of our accompanying discussion of the properties of homogeneous ellipsoids]]. That is, let's examine a model with <math>~a_1 = 1.0</math> and … | |||

<table border="0" align="center" width="80%"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~\frac{a_3}{a_1} = 0.582724 \, ,</math></td> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~e = 0.81267 \, ,</math></td> | |||

<td align="center"> </td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~A_1 = A_2 = 0.51589042 \, ,</math></td> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~A_3 = 0.96821916 \, ,</math></td> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~I_\mathrm{BT} = 1.360556 \, .</math></td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

In the meridional <math>~(\varpi, z)</math> plane, the surface of this oblate-spheroidal configuration — identified by the thick, solid-black curve below, in Figure 1 — is defined by the expression, | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\frac{\varpi^2}{a_1^2} + \frac{z^2}{a_3^2}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left" colspan="2"> | |||

<math>~1 </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~ z</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\pm a_3 [1 - \varpi^2]^{1 / 2} \, ,</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="right"> for <math>~0 \le | \varpi | \le 1 \, .</math></td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

Throughout the interior of this configuration, each associated <math>~\Phi_\mathrm{eff}</math> = constant, equipotential surface is defined by the expression, | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\phi_\mathrm{choice} \equiv \frac{\Phi_\mathrm{eff}}{\pi G \rho} + I_\mathrm{BT}a_1^2 </math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left" colspan="1"> | |||

<math>~\biggl( A_1 - \frac{\omega_0^2}{2\pi G \rho}\biggr) \varpi^2 + A_3 z^2 </math> | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | |||

(Notice that, written in this manner, <math>~\phi_\mathrm{choice}</math> assumes its minimum value (zero) when <math>~(\varpi, z) = (0, 0)</math>, that is, at the center of the configuration.) This means that, | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~z </math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

< | <math>~=</math> | ||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\pm \frac{1}{\sqrt{A_3}} \biggl[ \phi_\mathrm{choice} - \biggl( A_1 - \frac{\omega_0^2}{2\pi G \rho}\biggr) \varpi^2\biggr]^{1 / 2} \, . </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

---- | |||

'''No Rotation''' | |||

When we do not consider the effects of rotation and plot, instead, just the equi-gravitational-potential surfaces, then | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~z </math> | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<math>2</math> | <math>~=</math> | ||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\pm \frac{1}{\sqrt{A_3}} \biggl[ \phi_\mathrm{choice} - A_1 \varpi^2\biggr]^{1 / 2} \, . </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

Because we know that the <math>~\Phi_\mathrm{grav}</math> = constant surfaces are all less flattened than the configuration itself, we should expect that the largest value of the potential that will arise inside — actually, on the surface of — the flattened spheroidal configuration will be found at <math>~(\varpi, z) = (1, 0)</math>, that is, when, | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~0 </math> | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math>~=</math> | ||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\pm \frac{1}{\sqrt{A_3}} \biggl[ \phi_\mathrm{choice} - A_1 \biggr]^{1 / 2} \, . </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~\phi_\mathrm{choice}\biggr|_\mathrm{max}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~ A_1 \, . </math> | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

So we will plot various equipotential surfaces having, <math>~0 < \phi_\mathrm{choice} < A_1 \, ,</math> recognizing that they will each cut through the equatorial plane <math>~(z = 0)</math> at the radial coordinate given by, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>~\varpi = \sqrt{\phi_\mathrm{choice}/A_1} \, .</math> | |||

</div> | |||

Next, we recognize that the largest equipotential surface that fits entirely within the surface of the oblate spheroidal configuration has the value of the potential that is found on the symmetry axis and at the pole of the spheroid, that is, at <math>~(\varpi, z) = (0, a_3) \, .</math> For this case we find, | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\phi_\mathrm{choice}\biggr|_\mathrm{mid}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~a_3^2 A_3 \, .</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

Hence, all equipotential surfaces having <math>~0 < \phi_\mathrm{choice} \le a_3^2 A_3</math> will lie entirely within the spheroid. But equipotential surfaces having <math>~a_3^2 A_3 < \phi_\mathrm{choice} \le A_1</math> will cut through the surface of the spheroid at the value of <math>~\varpi</math> where "the two values of z<sup>2</sup> match," that is, where, | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~a_3^2(1-\varpi^2)</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\frac{1}{A_3} \biggl[ \phi_\mathrm{choice} - A_1 \varpi^2\biggr] </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\Rightarrow~~~\varpi </math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\biggl[ \frac{\phi_\mathrm{choice} - a_3^2 A_3}{ A_1 - a_3^2 A_3 } \biggr]^{1 / 2} \, .</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

Therefore, for the example model parameters specified above, our selection of equipotential surfaces to plot should be guided by the following constraints. | |||

<table border="1" align="center" cellpadding="8" width="80%"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center" colspan="2">Equipotential Contour Lies …</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center" colspan="1" width="50%">Entirely Inside Spheroid's Surface</td> | |||

<td align="center" colspan="1">Partially Outside Spheroid's Surface</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center" colspan="1"><math>~0 < \phi_\mathrm{choice} < 0.32878</math></td> | |||

<td align="center" colspan="1"><math>~0.32878 < \phi_\mathrm{choice} < 0.51589</math></td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center" colspan="1"><math>~0 \le \varpi \le (\phi_\mathrm{choice}/0.51589)^{1 / 2}</math></td> | |||

<td align="center" colspan="1"><math>~\biggl[ \frac{\phi_\mathrm{choice} - 0.32878}{ 0.18711 } \biggr]^{1 / 2} \le \varpi \le (\phi_\mathrm{choice}/0.51589)^{1 / 2}</math></td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr><td align="left" colspan="2"> | |||

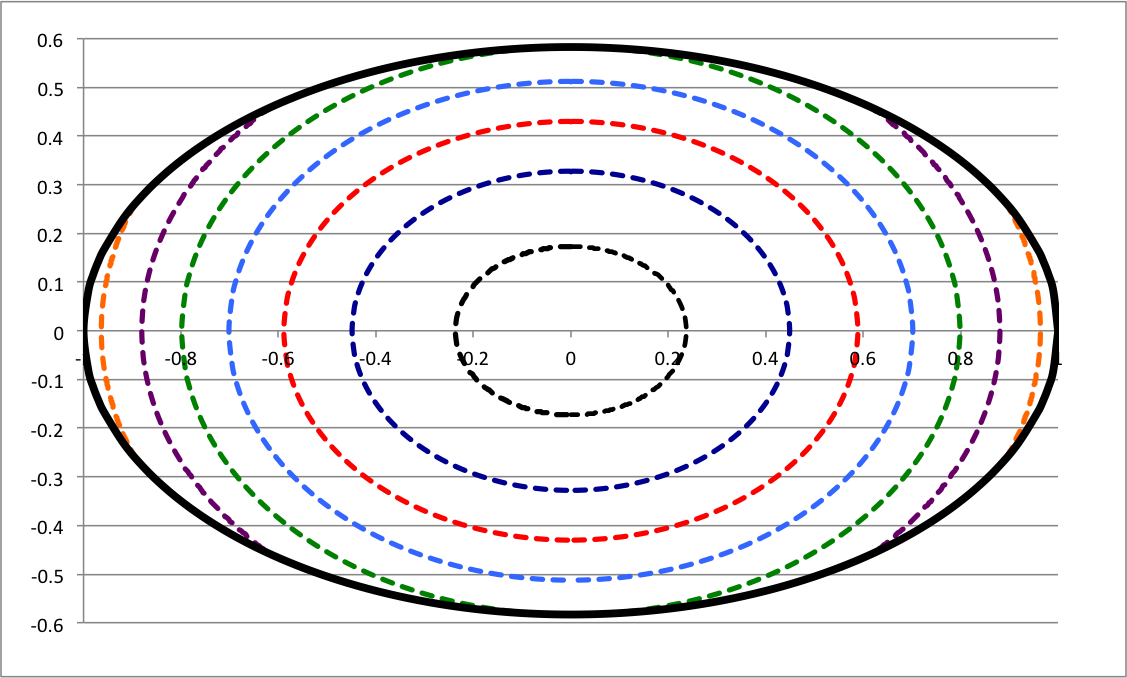

<div align="center">'''Figure 1: Meridional Plane Cross-section'''<br /> | |||

[[File:MacAtJacBifurcationJustGravity01.png|550px|center|Maclaurin Spheroid Cross-section at Jacobi Bifurcation]]</div> | |||

''Solid black curve'': Surface of oblate spheroid having a<sub>3</sub>/a<sub>1</sub> = 0.582724. ''Dashed curves'': Equi-gravitational-potential contours plotted in increments of <math>~\Delta\phi_\mathrm{choice} = 0.075</math>; specifically, <math>~\phi_\mathrm{choice}</math> = 0.029 (black), 0.104 (dark blue), 0.179 (red), 0.254 (light blue), 0.329 (green), 0.404 (purple), and 0.479 (orange). | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

---- | |||

'''With Rotation''' | |||

This expression is only applicable to our physical problem under the following conditions: | |||

<ol> | |||

<li> | |||

The argument of the square root must not be negative, that is, <math>~\varpi</math> must be confined to the range, | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~0 \le | \varpi |</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~\le</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\biggl[ \phi_\mathrm{choice}\biggl( A_1 - \frac{\omega_0^2}{2\pi G \rho}\biggr)^{-1 }\biggr]^{1 / 2} \, .</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

Note that, in turn, in order to ensure that the argument of ''this'' square root is not negative, we should only explore rotation rates for which <math>~\omega_0^2/(2\pi G \rho) \le A_1 \, .</math> | |||

</li> | |||

<li> | |||

In order that our equipotential surface be relevant only to the ''interior'' of our configuration, for every allowed value of <math>~\varpi ,</math> the value of <math>~z</math> corresponding to the potential surface must be less than or equal to the value of <math>~z</math> at the surface of the configuration. That is, | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~a_3^2(1-\varpi^2) </math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~\le</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\frac{1}{A_3} \biggl[ \phi_\mathrm{choice} - \biggl( A_1 - \frac{\omega_0^2}{2\pi G \rho}\biggr) \varpi^2\biggr]</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~\biggl( A_1 - \frac{\omega_0^2}{2\pi G \rho} - a_3^2 A_3^2 \biggr) \varpi^2 </math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~\le</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\phi_\mathrm{choice} - a_3^2 A_3^2 </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</li> | |||

</ol> | |||

==Equilibrium Structure== | ==Equilibrium Structure== | ||

| Line 168: | Line 425: | ||

To obtain the equilibrium structure of Maclaurin spheroids, we will adopt the [[User:Tohline/AxisymmetricConfigurations/SolutionStrategies#Technique|technique outlined earlier for determining the structure of axisymmetric configurations]]. Specifically, the algebraic expression, | To obtain the equilibrium structure of Maclaurin spheroids, we will adopt the [[User:Tohline/AxisymmetricConfigurations/SolutionStrategies#Technique|technique outlined earlier for determining the structure of axisymmetric configurations]]. Specifically, the algebraic expression, | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math>H + \Phi_\mathrm{eff} = C_\mathrm{B}</math> , | <math>~H + \Phi_\mathrm{eff} = C_\mathrm{B}</math> , | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

must be solved in conjunction with the [[User:Tohline/AxisymmetricConfigurations/PGE#Governing_Equations|Poisson equation written in cylindrical coordinates for axisymmetric configurations]], namely, | must be solved in conjunction with the [[User:Tohline/AxisymmetricConfigurations/PGE#Governing_Equations|Poisson equation written in cylindrical coordinates for axisymmetric configurations]], namely, | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

\frac{1}{\varpi} \frac{\partial }{\partial\varpi} \biggl[ \varpi \frac{\partial \Phi}{\partial\varpi} \biggr] + \frac{\partial^2 \Phi}{\partial z^2} = 4\pi G \rho . | ~\frac{1}{\varpi} \frac{\partial }{\partial\varpi} \biggl[ \varpi \frac{\partial \Phi}{\partial\varpi} \biggr] + \frac{\partial^2 \Phi}{\partial z^2} = 4\pi G \rho . | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

===Expression for Effective Potential=== | ===Expression for Effective Potential=== | ||

For any value of the eccentricity, <math>e</math>, the [[User:Tohline/Apps/MaclaurinSpheroids#Gravitational_Potential|above expression for the gravitational potential]] satisfies this two-dimensional Poisson equation. Furthermore, an algebraic expression defining the centrifugal potential inside a uniformly rotating configuration can be drawn from our accompanying table that summarizes the properties of various [[User:Tohline/AxisymmetricConfigurations/SolutionStrategies#SRPtable|simple rotation profiles]]. Together, these relations give us the relevant expression for the effective potential, namely, | For any value of the eccentricity, <math>~e</math>, the [[User:Tohline/Apps/MaclaurinSpheroids#Gravitational_Potential|above expression for the gravitational potential]] satisfies this two-dimensional Poisson equation. Furthermore, an algebraic expression defining the centrifugal potential inside a uniformly rotating configuration can be drawn from our accompanying table that summarizes the properties of various [[User:Tohline/AxisymmetricConfigurations/SolutionStrategies#SRPtable|simple rotation profiles]]. Together, these relations give us the relevant expression for the effective potential, namely, | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| Line 191: | Line 448: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

This expression contains two constants, <math>C_\mathrm{B}</math> and <math>\omega_0</math>, that can be determined from relevant boundary conditions. | This expression contains two constants, <math>~C_\mathrm{B}</math> and <math>~\omega_0</math>, that can be determined from relevant boundary conditions. | ||

===Apply Boundary Conditions=== | ===Apply Boundary Conditions=== | ||

The enthalpy should go to zero everywhere on the surface of the spheroid. By pinning the surface down at two points and setting <math>H=0</math> at both of these locations, we can determine the two unknown constants in the above expression. We choose to pin down the edge of the configuration in the equatorial plane — ''i.e.'', at <math>(\varpi,z) = (a_1,0)</math> — and along the symmetry axis at the pole — ''i.e.'', at <math>(\varpi,z) = (0,a_3)</math>. From the boundary condition at the pole, we derive the Bernoulli constant, specifically, | The enthalpy should go to zero everywhere on the surface of the spheroid. By pinning the surface down at two points and setting <math>~H=0</math> at both of these locations, we can determine the two unknown constants in the above expression. We choose to pin down the edge of the configuration in the equatorial plane — ''i.e.'', at <math>(\varpi,z) = (a_1,0)</math> — and along the symmetry axis at the pole — ''i.e.'', at <math>(\varpi,z) = (0,a_3)</math>. From the boundary condition at the pole, we derive the Bernoulli constant, specifically, | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| Line 202: | Line 459: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

and from the boundary condition in the equatorial plane we derive the rotational angular velocity, specifically, | and from the boundary condition in the equatorial plane we derive the rotational angular velocity, specifically, | ||

<div align="center" id="EquilibriumFrequency"> | |||

<table align="center" border="0" cellpadding="5"> | <table align="center" border="0" cellpadding="5"> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| Line 211: | Line 469: | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

= | ~= | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

| Line 229: | Line 487: | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

= | ~= | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

2\pi G \rho \biggl[ A_1 - A_3 (1-e^2) \biggr] | 2\pi G \rho \biggl[ A_1 - A_3 (1-e^2) \biggr] \, . | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center" colspan="3"> | |||

[<b>[[User:Tohline/Appendix/References#T78|<font color="red">T78</font>]]</b>], §4.5, p. 86, Eq. (52)<br /> | |||

[<b>[[User:Tohline/Appendix/References#ST83|<font color="red">ST83</font>]]</b>], §7.3, p. 172, Eq. (7.3.18) | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

</div> | |||

Plugging these constants into the expression for the enthalpy results in the desired solution, | Plugging these constants into the expression for the enthalpy results in the desired solution, | ||

| Line 250: | Line 515: | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

= | ~= | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

| Line 261: | Line 526: | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

[[File:CommentButton02.png|right|100px|Comment by J. E. Tohline: In Tassoul (1978), the leading coefficient in the expression for the pressure — and, hence, the central pressure — is too large by a factor of 2.]]We know from our [[User:Tohline/SR#Barotropic_Structure|separate discussion of supplemental, barotropic equations of state]] that, for a uniform-density, <math>~n = 0</math> polytropic configuration, the pressure is related to the enthalpy via the expression, <math>~P = H\rho</math>. Hence, we conclude that, | |||

<table align="center" border="0" cellpadding="5"> | <table align="center" border="0" cellpadding="5"> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| Line 271: | Line 536: | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

= | ~= | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

| Line 279: | Line 544: | ||

\biggr] | \biggr] | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center" colspan="3"> | |||

[<b>[[User:Tohline/Appendix/References#T78|<font color="red">T78</font>]]</b>], §4.5, p. 86, Eq. (51)<br /> | |||

[<b>[[User:Tohline/Appendix/References#ST83|<font color="red">ST83</font>]]</b>], §7.3, p. 172, Eqs. (7.3.16) & (7.3.17) | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

| Line 290: | Line 561: | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

= | ~= | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

| Line 303: | Line 574: | ||

where, | where, | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math>~ | ||

P_0 \equiv \frac{2}{3}\pi G \rho^2 a_\mathrm{mean}^2 = \frac{2}{3}\pi G \rho^2 a_1^2 (1-e^2)^{1/3} . | P_0 \equiv \frac{2}{3}\pi G \rho^2 a_\mathrm{mean}^2 = \frac{2}{3}\pi G \rho^2 a_1^2 (1-e^2)^{1/3} . | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

=Related Wikipedia Discussions= | =Related Wikipedia Discussions= | ||

Latest revision as of 21:19, 24 August 2020

Maclaurin Spheroids (axisymmetric structure)

|

|---|

| | Tiled Menu | Tables of Content | Banner Video | Tohline Home Page | |

There is no particular reason why one should guess ahead of time that the equilibrium properties of any rotating, self-gravitating configuration should be describable in terms of analytic functions. As luck would have it, however, the gravitational potential at the surface of and inside an homogeneous spheroid is expressible analytically. (The potential is constant on concentric spheroidal surfaces that generally have a different axis ratio from the spheroidal mass distribution.) Furthermore, the gradient of the gravitational potential is separable in cylindrical coordinates, proving to be a simple linear function of both <math>\varpi</math> and <math>~z</math>.

If the spheroid is uniformly rotating, this behavior conspires nicely with the behavior of the centrifugal acceleration — which also will be a linear function of <math>\varpi</math> — to permit an analytic (and integrable) prescription of the pressure gradient. Not surprisingly, it resembles the functional form of the pressure gradient that is required to balance the gravitational force in uniform-density spheres.

As a consequence of this good fortune, the equilibrium structure of a uniformly rotating, uniform-density <math>~(n = 0)</math>, axisymmetric configuration can be shown to be precisely an oblate spheroid whose internal properties are describable in terms of analytic expressions. As we show in an accompanying discussion, the angular velocity that is required to keep a self-gravitating spheroid of a specified eccentricity in equilibrium can be obtained from a theorem — we will refer to it as Maclaurin's Theorem — that was derived from purely geometric arguments over 270 years ago by Colin Maclaurin (1742) in A Treatise of Fluxions. This result has been enumerated in many subsequent publications (e.g., Tassoul 1978; Chandrasekhar 1987). It should be appreciated that both Volume I and Volume II of Maclaurin's (1742) Treatise can now be accessed online via Google Books. Selected excerpts from these two volumes are shown in our accompanying discussion.

Properties of Uniform-Density Spheroids

Surface Definition

Let <math>~a_1</math> be the equatorial radius and <math>~a_3</math> the polar radius of a uniform-density object whose surface is defined precisely by an oblate spheroid. The degree of flattening of the object may be parameterized in terms of the axis ratio <math>~a_3/a_1</math>, or in terms of the object's eccentricity,

<math>

e \equiv \biggl[ 1 - \biggl(\frac{a_3}{a_1}\biggr)^2 \biggr]^{1/2} .

</math>

(For an oblate spheroid, <math>~a_3 \leq a_1</math>; hence, the eccentricity is restricted to the range <math>~0 \leq e \leq 1</math>.) The meridional cross-section of such a spheroid is an ellipse with the same eccentricity. The foci of this ellipse lie in the equatorial plane of the spheroid at a distance <math>~\varpi = ea_1</math> from the minor <math>~(z)</math> axis.

Mean Radius

For purposes of normalization, it will be useful to define the mean radius of the spheroid as,

<math> ~a_\mathrm{mean} \equiv \biggl[a_1^2 a_3 \biggr]^{1/3} = a_1 (1 - e^2)^{1/6} , </math>

which is equivalent to the radius of a sphere in the limit <math>~a_3 = a_1</math> <math>~(e=0)</math>.

Mass

The total mass of such a spheroid is,

<math>

M = \frac{4\pi}{3}~a_1^2 a_3 \rho = \frac{4\pi}{3}~a_1^3 \rho (1 - e^2)^{1/2} .

</math>

Gravitational Potential

In an accompanying discussion entitled, Properties of Homogeneous Ellipsoids, an expression is given for the gravitational potential <math>\Phi(\vec{x})</math> at an internal point or on the surface of an homogeneous ellipsoid with semi-axes <math>~(x,y,z) = (a_1,a_2,a_3)</math>. For an homogeneous, oblate spheroid in which <math>~a_1 = a_2 \geq a_3</math>, this analytic expression defining the potential reduces to the form,

<math> \Phi(\varpi,z) = -\pi G \rho \biggl[ I_\mathrm{BT} a_1^2 - \biggl(A_1 \varpi^2 + A_3 z^2 \biggr) \biggr], </math>

[ST83], §7.3, p. 169, Eq. (7.3.1)

where, the coefficients <math>~A_1</math>, <math>~A_3</math>, and <math>~I_\mathrm{BT}</math> are functions only of the spheroid's eccentricity. Specifically,

|

<math> ~A_1 </math> |

<math> ~= </math> |

<math> \frac{1}{e^2} \biggl[\frac{\sin^{-1}e}{e} - (1-e^2)^{1/2} \biggr](1-e^2)^{1/2} \, ; </math> |

|

<math> ~A_3 </math> |

<math> ~= </math> |

<math> \frac{2}{e^2} \biggl[(1-e^2)^{-1/2} -\frac{\sin^{-1}e}{e} \biggr](1-e^2)^{1/2} \, ; </math> |

|

<math> ~I_\mathrm{BT} </math> |

<math> ~= </math> |

<math> ~2A_1 + A_3(1-e^2) = 2 (1-e^2)^{1/2} \biggl[ \frac{\sin^{-1}e}{e}\biggr] \, . </math> |

|

[ST83], §7.3, p. 170, Eqs. (7.3.8) |

||

Note that these three expressions have the following values in the limit of a sphere <math>~(e=0)</math> or in the limit of an infinitesimally thin disk <math>~(e=1)</math>:

|

Limiting Values |

||

|

|

<math>~e=0</math> |

<math>~e=1</math> |

|

<math>~A_1</math> |

<math>\frac{2}{3}</math> |

<math>~0</math> |

|

<math>~A_3</math> |

<math>\frac{2}{3}</math> |

<math>~2</math> |

|

<math>~I_\mathrm{BT}</math> |

<math>~2</math> |

<math>~0</math> |

Example Equi-gravitational-potential Contours

As an example, let's examine the gravitational potential everywhere inside (and on the surface) of the oblate spheroid whose properties are presented in the first row of model data in Table 1 of our accompanying discussion of the properties of homogeneous ellipsoids. That is, let's examine a model with <math>~a_1 = 1.0</math> and …

| <math>~\frac{a_3}{a_1} = 0.582724 \, ,</math> | <math>~e = 0.81267 \, ,</math> | |

| <math>~A_1 = A_2 = 0.51589042 \, ,</math> | <math>~A_3 = 0.96821916 \, ,</math> | <math>~I_\mathrm{BT} = 1.360556 \, .</math> |

In the meridional <math>~(\varpi, z)</math> plane, the surface of this oblate-spheroidal configuration — identified by the thick, solid-black curve below, in Figure 1 — is defined by the expression,

|

<math>~\frac{\varpi^2}{a_1^2} + \frac{z^2}{a_3^2}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~1 </math> |

|

|

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~ z</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\pm a_3 [1 - \varpi^2]^{1 / 2} \, ,</math> |

for <math>~0 \le | \varpi | \le 1 \, .</math> |

Throughout the interior of this configuration, each associated <math>~\Phi_\mathrm{eff}</math> = constant, equipotential surface is defined by the expression,

|

<math>~\phi_\mathrm{choice} \equiv \frac{\Phi_\mathrm{eff}}{\pi G \rho} + I_\mathrm{BT}a_1^2 </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl( A_1 - \frac{\omega_0^2}{2\pi G \rho}\biggr) \varpi^2 + A_3 z^2 </math> |

(Notice that, written in this manner, <math>~\phi_\mathrm{choice}</math> assumes its minimum value (zero) when <math>~(\varpi, z) = (0, 0)</math>, that is, at the center of the configuration.) This means that,

|

<math>~z </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\pm \frac{1}{\sqrt{A_3}} \biggl[ \phi_\mathrm{choice} - \biggl( A_1 - \frac{\omega_0^2}{2\pi G \rho}\biggr) \varpi^2\biggr]^{1 / 2} \, . </math> |

No Rotation

When we do not consider the effects of rotation and plot, instead, just the equi-gravitational-potential surfaces, then

|

<math>~z </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\pm \frac{1}{\sqrt{A_3}} \biggl[ \phi_\mathrm{choice} - A_1 \varpi^2\biggr]^{1 / 2} \, . </math> |

Because we know that the <math>~\Phi_\mathrm{grav}</math> = constant surfaces are all less flattened than the configuration itself, we should expect that the largest value of the potential that will arise inside — actually, on the surface of — the flattened spheroidal configuration will be found at <math>~(\varpi, z) = (1, 0)</math>, that is, when,

|

<math>~0 </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\pm \frac{1}{\sqrt{A_3}} \biggl[ \phi_\mathrm{choice} - A_1 \biggr]^{1 / 2} \, . </math> |

|

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~\phi_\mathrm{choice}\biggr|_\mathrm{max}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ A_1 \, . </math> |

So we will plot various equipotential surfaces having, <math>~0 < \phi_\mathrm{choice} < A_1 \, ,</math> recognizing that they will each cut through the equatorial plane <math>~(z = 0)</math> at the radial coordinate given by,

<math>~\varpi = \sqrt{\phi_\mathrm{choice}/A_1} \, .</math>

Next, we recognize that the largest equipotential surface that fits entirely within the surface of the oblate spheroidal configuration has the value of the potential that is found on the symmetry axis and at the pole of the spheroid, that is, at <math>~(\varpi, z) = (0, a_3) \, .</math> For this case we find,

|

<math>~\phi_\mathrm{choice}\biggr|_\mathrm{mid}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~a_3^2 A_3 \, .</math> |

Hence, all equipotential surfaces having <math>~0 < \phi_\mathrm{choice} \le a_3^2 A_3</math> will lie entirely within the spheroid. But equipotential surfaces having <math>~a_3^2 A_3 < \phi_\mathrm{choice} \le A_1</math> will cut through the surface of the spheroid at the value of <math>~\varpi</math> where "the two values of z2 match," that is, where,

|

<math>~a_3^2(1-\varpi^2)</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{1}{A_3} \biggl[ \phi_\mathrm{choice} - A_1 \varpi^2\biggr] </math> |

|

<math>~\Rightarrow~~~\varpi </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl[ \frac{\phi_\mathrm{choice} - a_3^2 A_3}{ A_1 - a_3^2 A_3 } \biggr]^{1 / 2} \, .</math> |

Therefore, for the example model parameters specified above, our selection of equipotential surfaces to plot should be guided by the following constraints.

| Equipotential Contour Lies … | |

| Entirely Inside Spheroid's Surface | Partially Outside Spheroid's Surface |

| <math>~0 < \phi_\mathrm{choice} < 0.32878</math> | <math>~0.32878 < \phi_\mathrm{choice} < 0.51589</math> |

| <math>~0 \le \varpi \le (\phi_\mathrm{choice}/0.51589)^{1 / 2}</math> | <math>~\biggl[ \frac{\phi_\mathrm{choice} - 0.32878}{ 0.18711 } \biggr]^{1 / 2} \le \varpi \le (\phi_\mathrm{choice}/0.51589)^{1 / 2}</math> |

|

Solid black curve: Surface of oblate spheroid having a3/a1 = 0.582724. Dashed curves: Equi-gravitational-potential contours plotted in increments of <math>~\Delta\phi_\mathrm{choice} = 0.075</math>; specifically, <math>~\phi_\mathrm{choice}</math> = 0.029 (black), 0.104 (dark blue), 0.179 (red), 0.254 (light blue), 0.329 (green), 0.404 (purple), and 0.479 (orange). |

|

With Rotation This expression is only applicable to our physical problem under the following conditions:

-

The argument of the square root must not be negative, that is, <math>~\varpi</math> must be confined to the range,

<math>~0 \le | \varpi |</math>

<math>~\le</math>

<math>~\biggl[ \phi_\mathrm{choice}\biggl( A_1 - \frac{\omega_0^2}{2\pi G \rho}\biggr)^{-1 }\biggr]^{1 / 2} \, .</math>

Note that, in turn, in order to ensure that the argument of this square root is not negative, we should only explore rotation rates for which <math>~\omega_0^2/(2\pi G \rho) \le A_1 \, .</math>

-

In order that our equipotential surface be relevant only to the interior of our configuration, for every allowed value of <math>~\varpi ,</math> the value of <math>~z</math> corresponding to the potential surface must be less than or equal to the value of <math>~z</math> at the surface of the configuration. That is,

<math>~a_3^2(1-\varpi^2) </math>

<math>~\le</math>

<math>~\frac{1}{A_3} \biggl[ \phi_\mathrm{choice} - \biggl( A_1 - \frac{\omega_0^2}{2\pi G \rho}\biggr) \varpi^2\biggr]</math>

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~\biggl( A_1 - \frac{\omega_0^2}{2\pi G \rho} - a_3^2 A_3^2 \biggr) \varpi^2 </math>

<math>~\le</math>

<math>~\phi_\mathrm{choice} - a_3^2 A_3^2 </math>

Equilibrium Structure

Governing Relations

To obtain the equilibrium structure of Maclaurin spheroids, we will adopt the technique outlined earlier for determining the structure of axisymmetric configurations. Specifically, the algebraic expression,

<math>~H + \Phi_\mathrm{eff} = C_\mathrm{B}</math> ,

must be solved in conjunction with the Poisson equation written in cylindrical coordinates for axisymmetric configurations, namely,

<math> ~\frac{1}{\varpi} \frac{\partial }{\partial\varpi} \biggl[ \varpi \frac{\partial \Phi}{\partial\varpi} \biggr] + \frac{\partial^2 \Phi}{\partial z^2} = 4\pi G \rho . </math>

Expression for Effective Potential

For any value of the eccentricity, <math>~e</math>, the above expression for the gravitational potential satisfies this two-dimensional Poisson equation. Furthermore, an algebraic expression defining the centrifugal potential inside a uniformly rotating configuration can be drawn from our accompanying table that summarizes the properties of various simple rotation profiles. Together, these relations give us the relevant expression for the effective potential, namely,

<math> \Phi_\mathrm{eff}(\varpi,z) = \Phi + \Psi = -\pi G \rho \biggl[ I_\mathrm{BT} a_1^2 - \biggl(A_1 \varpi^2 + A_3 z^2 \biggr) \biggr] - \frac{1}{2}\varpi^2 \omega_0^2 . </math>

Hence, the enthalpy throughout the configuration must be given by the expression,

<math> H(\varpi,z) = C_\mathrm{B} + \pi G \rho \biggl[ I_\mathrm{BT} a_1^2 - \biggl(A_1 \varpi^2 + A_3 z^2 \biggr) \biggr] + \frac{1}{2}\varpi^2 \omega_0^2 . </math>

This expression contains two constants, <math>~C_\mathrm{B}</math> and <math>~\omega_0</math>, that can be determined from relevant boundary conditions.

Apply Boundary Conditions

The enthalpy should go to zero everywhere on the surface of the spheroid. By pinning the surface down at two points and setting <math>~H=0</math> at both of these locations, we can determine the two unknown constants in the above expression. We choose to pin down the edge of the configuration in the equatorial plane — i.e., at <math>(\varpi,z) = (a_1,0)</math> — and along the symmetry axis at the pole — i.e., at <math>(\varpi,z) = (0,a_3)</math>. From the boundary condition at the pole, we derive the Bernoulli constant, specifically,

<math> C_\mathrm{B} = - \pi G \rho \biggl[ I_\mathrm{BT} a_1^2 - A_3 a_3^2 \biggr] = - \pi G \rho a_1^2 \biggl[ I_\mathrm{BT} - A_3 (1-e^2) \biggr] ; </math>

and from the boundary condition in the equatorial plane we derive the rotational angular velocity, specifically,

|

<math> \frac{1}{2}a_1^2 \omega_0^2 </math> |

<math> ~= </math> |

<math> - C_\mathrm{B} - \pi G \rho \biggl[ I_\mathrm{BT} a_1^2 - A_1 a_1^2 \biggr] </math> |

|

<math> \Rightarrow ~~~~~ \omega_0^2 </math> |

<math> ~= </math> |

<math> 2\pi G \rho \biggl[ A_1 - A_3 (1-e^2) \biggr] \, . </math> |

|

[T78], §4.5, p. 86, Eq. (52) |

||

Plugging these constants into the expression for the enthalpy results in the desired solution,

|

<math> H(\varpi,z) </math> |

<math> ~= </math> |

<math> \pi G \rho a_1^2 A_3 (1-e^2)\biggl[1 - \biggl( \frac{\varpi}{a_1} \biggr)^2 - \biggl( \frac{z}{a_3} \biggr)^2 \biggr] . </math> |

We know from our separate discussion of supplemental, barotropic equations of state that, for a uniform-density, <math>~n = 0</math> polytropic configuration, the pressure is related to the enthalpy via the expression, <math>~P = H\rho</math>. Hence, we conclude that,

|

<math> P(\varpi,z) </math> |

<math> ~= </math> |

<math> \pi G \rho^2 a_1^2 A_3 (1-e^2)\biggl[1 - \biggl( \frac{\varpi}{a_1} \biggr)^2 - \biggl( \frac{z}{a_3} \biggr)^2 \biggr] </math> |

|

[T78], §4.5, p. 86, Eq. (51) |

||

|

<math> \Rightarrow ~~~~ \frac{P}{P_0} </math> |

<math> ~= </math> |

<math> \frac{3}{2} A_3 (1-e^2)^{2/3}\biggl[1 - \biggl( \frac{\varpi}{a_1} \biggr)^2 - \biggl( \frac{z}{a_3} \biggr)^2 \biggr] , </math> |

where,

<math>~ P_0 \equiv \frac{2}{3}\pi G \rho^2 a_\mathrm{mean}^2 = \frac{2}{3}\pi G \rho^2 a_1^2 (1-e^2)^{1/3} . </math>

Related Wikipedia Discussions

|

|---|

|

© 2014 - 2021 by Joel E. Tohline |