Difference between revisions of "User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/BiPolytropes"

(→Interface Conditions: Work on Table 2) |

(→Setup) |

||

| (37 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

=BiPolytropes= | =BiPolytropes= | ||

{{LSU_HBook_header}} | {{LSU_HBook_header}} | ||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

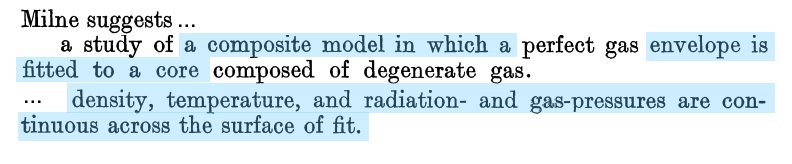

While [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/Polytropes#Polytropic_Spheres|polytropic spheres]] can give us useful ''general'' insight into the internal structure of stars, they do not faithfully represent the detailed structure of most stars, in part, because the equation of state that is most relevant to the densest regions of a star usually is different from the equation of state that is relevant to the star's envelope. As is highlighted in the following excerpt from [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1931MNRAS..91..472C Cowling (1931)], [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1930MNRAS..91....4M Milne (1930)] was among the first to suggest that more realism could be achieved by constructing what is now commonly referred to as a bipolytrope: a composite model in which the envelope, obeying one equation of state — described by polytropic index <math>n_e</math> — is fitted to a core obeying a different equation of state — described by polytropic index <math>n_c</math>. | While [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/Polytropes#Polytropic_Spheres|polytropic spheres]] can give us useful ''general'' insight into the internal structure of stars, they do not faithfully represent the detailed structure of most stars, in part, because the equation of state that is most relevant to the densest regions of a star usually is different from the equation of state that is relevant to the star's envelope. As is highlighted in the following excerpt from [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1931MNRAS..91..472C Cowling (1931)], [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1930MNRAS..91....4M Milne (1930)] was among the first to suggest that more realism could be achieved by constructing what is now commonly referred to as a bipolytrope: a composite model in which the envelope, obeying one equation of state — described by polytropic index <math>n_e</math> — is fitted to a core obeying a different equation of state — described by polytropic index <math>n_c</math>. | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<table border="1" cellpadding="5"> | <table border="1" cellpadding="5" width="80%"> | ||

<tr><td align="center"> | |||

Text extracted<sup>†</sup> from p. 472 of [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1931MNRAS..91..472C T. G. Cowling (1931)]<p></p> | |||

"''Note on the Fitting of Polytropic Models in the Theory of Stellar Structure''"<p></p> | |||

MNRAS, 91, 472-478 © Royal Astronomical Society | |||

</td></tr> | |||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

[[Image:CowlingRE_Milne1931.jpg|500px|center|Cowling (1931)]] | |||

<!-- [[Image:AAAwaiting01.png|400px|center|Norman & Wilson (1978)]] --> | |||

< | |||

[[Image: | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr><td align="left"><sup>†</sup>Text displayed here, as a single digital image, with presentation order & layout modified from the original publication.</td></tr> | |||

</table> | </table> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

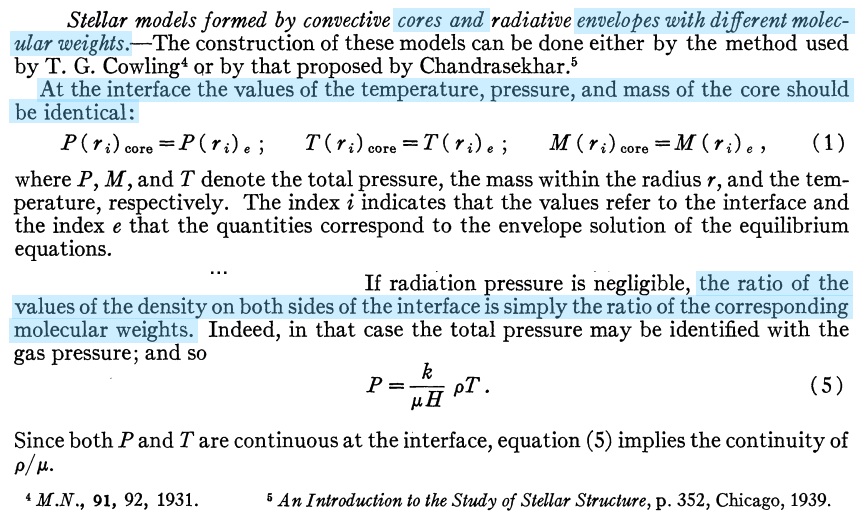

[http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1930MNRAS..91....4M Milne (1930)] envisioned that the temperature, {{User:Tohline/Math/VAR_Temperature01}}, and pressure, {{User:Tohline/Math/VAR_Pressure01}}, should be "continuous across the surface of fit." Given that {{User:Tohline/Math/VAR_Temperature01}} and {{User:Tohline/Math/VAR_Pressure01}} are continuous, he envisioned that the gas density, {{User:Tohline/Math/VAR_Density01}}, should be continuous across the surface of fit as well. [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1942ApJ....96..161S Schönberg & Chandrasekhar (1942)] later pointed out — see the following journal article excerpt — that, if the core and envelope have different molecular weights, it is the ratio {{User:Tohline/Math/VAR_Density01}}/{{User:Tohline/Math/MP_MeanMolecularWeight}} that should be continuous across the interface. A discontinuous jump in {{User:Tohline/Math/MP_MeanMolecularWeight}} at the interface — for example, switching from a pure helium core to an envelope whose dominant element is hydrogen — will therefore lead to a discontinuous jump in {{User:Tohline/Math/VAR_Density01}} at the interface. | [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1930MNRAS..91....4M Milne (1930)] envisioned that the temperature, {{User:Tohline/Math/VAR_Temperature01}}, and pressure, {{User:Tohline/Math/VAR_Pressure01}}, should be "continuous across the surface of fit." Given that {{User:Tohline/Math/VAR_Temperature01}} and {{User:Tohline/Math/VAR_Pressure01}} are continuous, he envisioned that the gas density, {{User:Tohline/Math/VAR_Density01}}, should be continuous across the surface of fit as well. [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1942ApJ....96..161S Schönberg & Chandrasekhar (1942)] later pointed out — see the following journal article excerpt — that, if the core and envelope have different molecular weights, it is the ratio {{User:Tohline/Math/VAR_Density01}}/{{User:Tohline/Math/MP_MeanMolecularWeight}} that should be continuous across the interface. A discontinuous jump in {{User:Tohline/Math/MP_MeanMolecularWeight}} at the interface — for example, switching from a pure helium core to an envelope whose dominant element is hydrogen — will therefore lead to a discontinuous jump in {{User:Tohline/Math/VAR_Density01}} at the interface. | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<table border="1" cellpadding="5"> | <table border="1" cellpadding="5" width="80%"> | ||

<tr> | <tr><td align="center"> | ||

Text excerpts<sup>†</sup> from §2 (pp. 161-162) of [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1942ApJ....96..161S Schönberg & Chandrasekhar (1942)]<p></p> | |||

"''On the Evolution of the Main-Sequence Stars''"<p></p> | |||

ApJ, 96, 161-172 © American Astronomicall Society | |||

</tr> | </td></tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

[[Image:SchonbergChandra1942.jpg|600px|center|Schönberg & Chandrasekhar (1942)]] | |||

<!-- [[Image:AAAwaiting01.png|400px|center|Norman & Wilson (1978)]] --> | |||

<!-- | |||

<imagemap> | <imagemap> | ||

Image: | Image:AAAwaiting01.png|600px|References | ||

rect 0 480 210 580 [[User:Tohline/PGE]] | rect 0 480 210 580 [[User:Tohline/PGE]] | ||

rect 260 480 850 580 [[User:Tohline/Appendix/References#C67]] | rect 260 480 850 580 [[User:Tohline/Appendix/References#C67]] | ||

desc none | desc none | ||

</imagemap> | </imagemap> | ||

--> | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr><td align="left"><sup>†</sup>Text displayed here, as a single digital image, with presentation order & layout modified from the original publication.</td></tr> | |||

</table> | </table> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

[http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1942ApJ....96..161S Schönberg & Chandrasekhar (1942)] furthermore pointed out — again, see the relevant article excerpt — that, when constructing a bipolytropic model, the mathematical function that specifies the mass enclosed inside a spherical radius <math>r</math> for the ''core'', <math>M(r)|_\mathrm{c}</math>, must give the same value as the mathematical function that specifies the mass enclosed inside a spherical radius <math>r</math> for the ''envelope'', <math>M(r)|_\mathrm{e}</math> ''at the radial location of the interface'', <math>r_i</math>. | [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1942ApJ....96..161S Schönberg & Chandrasekhar (1942)] furthermore pointed out — again, see the relevant article excerpt — that, when constructing a bipolytropic model, the mathematical function that specifies the mass enclosed inside a spherical radius <math>r</math> for the ''core'', <math>M(r)|_\mathrm{c}</math>, must give the same value as the mathematical function that specifies the mass enclosed inside a spherical radius <math>r</math> for the ''envelope'', <math>M(r)|_\mathrm{e}</math> ''at the radial location of the interface'', <math>r_i</math>. | ||

| Line 47: | Line 55: | ||

==Setup== | ==Setup== | ||

Here we lay the mathematical foundation for building a spherically symmetric structure in which the core and the envelope are described by different | Here we lay the mathematical foundation for building a spherically symmetric structure in which the core and the envelope are described by different barotropic equations of state. The <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> and <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> columns of Table 1 provide the relevant set of relations for a structure in which the core and envelope obey polytropic equations of state that have, respectively, polytropic indexes <math>n_c</math> and <math>n_e</math>. Drawing on our [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/Polytropes#Lane-Emden_Equation|related discussion of isolated polytropes]], it is clear that the structural profile in both regions should be given by a solution of the | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<span id="LaneEmdenEquation"><font color="#770000">'''Lane-Emden Equation'''</font></span> | <span id="LaneEmdenEquation"><font color="#770000">'''Lane-Emden Equation'''</font></span> | ||

| Line 53: | Line 61: | ||

{{User:Tohline/Math/EQ_SSLaneEmden01}} | {{User:Tohline/Math/EQ_SSLaneEmden01}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

If either region is governed by an isothermal, rather than polytropic, equation of state then, as we have discussed in the context of both [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/IsothermalSphere#Isothermal_Sphere|isolated]] and [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/BonnorEbert#Pressure-Bounded_Isothermal_Sphere|pressure-bounded isothermal spheres]] and as is shown by equation (374) of [[User:Tohline/Appendix/References#C67|[<b><font color="red">C67</font></b>]]], the structural profile should be given instead by a solution of the related equation, | |||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math>\ | <math> | ||

\frac{1}{\chi^2} \frac{d}{d\chi} \biggl( \chi^2 \frac{d\psi}{d\chi} \biggr) = e^{-\psi} \, . | |||

</math> | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

The <math>1^\mathrm{st}</math> column of Table 1 provides the relevant set of associated structural relations for an isothermal core. | |||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center" id="TableSetup"> | ||

<table border="1" cellpadding="5"> | <table border="1" cellpadding="5" width="80%"> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="center" colspan="3"> | <td align="center" colspan="3"> | ||

| Line 109: | Line 115: | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

\frac{1}{\xi^2} \frac{d}{d\xi} \biggl( \xi^2 \frac{d\theta}{d\xi} \biggr) = \theta^{n_c} | \frac{1}{\xi^2} \frac{d}{d\xi} \biggl( \xi^2 \frac{d\theta}{d\xi} \biggr) = - \theta^{n_c} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| Line 119: | Line 125: | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

\frac{1}{\eta^2} \frac{d}{d\eta} \biggl( \eta^2 \frac{d\phi}{d\eta} \biggr) = \phi^{n_e} | \frac{1}{\eta^2} \frac{d}{d\eta} \biggl( \eta^2 \frac{d\phi}{d\eta} \biggr) = - \phi^{n_e} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| Line 243: | Line 249: | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math>4\pi \biggl[ \frac{(n_c + 1) | <math>4\pi \biggl[ \frac{(n_c + 1)K_c}{4\pi G} \biggr]^{3/2} \rho_0^{(3-n_c)/(2n_c)} \biggl(-\xi^2 \frac{d\theta}{d\xi} \biggr)</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

| Line 309: | Line 315: | ||

<!-- END RIGHT BLOCK details --> | <!-- END RIGHT BLOCK details --> | ||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="left" colspan="3"> | |||

<font color="red">'''NOTE typed on 13 May 2019:'''</font> Prior to this date, in both the middle and right-hand colums, the RHS of the ''polytropic'' version of the Lane-Emden equation incorrectly had a ''positive'' sign. This was a type-setting error that has now been corrected. | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

===Polytropic Core=== | |||

Using the notation established in Table 1, if the core obeys a polytropic equation of state, the variable <math>\xi</math> will denote the dimensionless radial coordinate through the core and the relevant solution is a function, <math>\theta(\xi)</math>, whose value goes to <math>1</math> and whose first derivative, <math>d\theta/d\xi</math>, goes to <math>0</math> at <math>\xi = 0</math>. Then, given a value of the central density, <math>\rho_0</math>, the density throughout the core is, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>\rho(\xi) = \rho_0 \theta(\xi)^{n_c}</math> ; | |||

</div> | |||

and, given a value of the polytropic constant in the core, <math>K_c</math>, the pressure throughout the core is, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>P(\xi) = K_c \rho_0^{1+1/n_c} \theta(\xi)^{n_c + 1}</math>. | |||

</div> | |||

Likewise, given <math>\rho_0</math> and <math>K_c</math>, the radial coordinate <math>r</math> (in dimensional rather than dimensionless units) and the mass enclosed within this radius, <math>M_r</math>, are given by the bottom two expressions shown in the <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> column of Table 1. | |||

The structure of an [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/Polytropes#Lane-Emden_Equation|isolated polytrope]] would be described by following the function <math>\theta(\xi)</math> all the way out to the surface, that is, to the radial location <math>\xi_\mathrm{surf}</math> where <math>\theta(\xi)</math> first drops to zero. (Analytic solutions of this type are presented elsewhere for [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/Polytropes#n_.3D_0_Polytrope|<math>n = 0</math>]], [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/Polytropes#n_.3D_1_Polytrope|<math>n = 1</math>]], and [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/Polytropes#n_.3D_5_Polytrope|<math>n = 5</math>]].) In constructing a bipolytrope, we will instead follow <math>\theta(\xi)</math> out to a radius <math>\xi_i < \xi_\mathrm{surf}</math>, then build an envelope whose inner radius — or ''base'' — is at the ''interface'' radius, <math>r_i</math>, that corresponds to <math>\xi_i</math>. For any choice of the pair of polytropic indexes, <math>n_c</math> and <math>n_e</math>, a series of bipolytropes can then be constructed by choosing a variety of different interface radii. | The structure of an [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/Polytropes#Lane-Emden_Equation|isolated polytrope]] would be described by following the function <math>\theta(\xi)</math> all the way out to the surface, that is, to the radial location <math>\xi_\mathrm{surf}</math> where <math>\theta(\xi)</math> first drops to zero. (Analytic solutions of this type are presented elsewhere for [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/Polytropes#n_.3D_0_Polytrope|<math>n = 0</math>]], [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/Polytropes#n_.3D_1_Polytrope|<math>n = 1</math>]], and [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/Polytropes#n_.3D_5_Polytrope|<math>n = 5</math>]].) In constructing a bipolytrope, we will instead follow <math>\theta(\xi)</math> out to a radius <math>\xi_i < \xi_\mathrm{surf}</math>, then build an envelope whose inner radius — or ''base'' — is at the ''interface'' radius, <math>r_i</math>, that corresponds to <math>\xi_i</math>. For any choice of the pair of polytropic indexes, <math>n_c</math> and <math>n_e</math>, a series of bipolytropes can then be constructed by choosing a variety of different interface radii. | ||

Again following | ===Polytropic Envelope=== | ||

Again following the notation of Table 1, we will use <math>\eta</math> to identify the dimensionless radial coordinate through the envelope, and the relevant solution of the Lane-Emden equation will be the function, <math>\phi(\eta)</math>. The ''particular'' solution that we seek for the envelope will differ from the solution obtained in the core not only because the governing polytropic index is different but also because the envelope solution will be constrained by different boundary conditions: The value of the function <math>\phi(\eta)</math> as well as its first derivative, <math>d\phi/d\eta</math>, must be specified at some radial location within the envelope. Because the envelope does not extend all the way to the center of the structure, it makes more sense to choose a solution in which <math>\phi</math> is set to unity at the inner edge of the envelope — that is, at the radial location <math>\eta_i</math> that corresponds to <math>r_i</math> — rather than at <math>\eta = 0</math>. By setting <math>\phi = 1</math> at the base of the envelope, it should be clear from the expression, | |||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| Line 322: | Line 346: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

(taken from the <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> column of Table 1) that <math>\rho_e</math> represents the value of the gas density at the base of the envelope. The value of <math>\rho_e</math> can be obtained from knowledge of the gas density at the outer edge of the core (''i.e.'', at <math>r_i</math>) combined with the specified | (taken from the <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> column of Table 1) that <math>\rho_e</math> represents the value of the gas density at the base of the envelope. The value of <math>\rho_e</math> can be obtained from knowledge of the gas density at the outer edge of the core (''i.e.'', at <math>r_i</math>) combined with the specified molecular-weight jump condition at the interface. Looking ahead at the first interface condition for a polytropic core catalogued in Table 2, we see more specifically that, after setting <math>\phi_i = 1</math>, | ||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math> | |||

\rho_e = \rho_0 \biggl( \frac{\mu_e}{\mu_c} \biggr) \theta^{n_c}_i \, . | |||

</math> | |||

</div> | |||

As we will show in connection with Table 3, the value of <math>d\phi/d\eta</math> at the base of the envelope (''i.e.'', at <math>r_i</math>) also will be set by the properties of the core at the interface — specifically, by the values of <math>(d\theta/d\xi)_i</math> and <math>\theta_i</math>. | |||

==Interface Conditions== | ==Interface Conditions== | ||

===The Schönberg-Chandrasekhar Condition=== | |||

The <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> and <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> columns of Table 1 provide the mathematical relations that are needed to implement the interface matching conditions specified by equation (1) of [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1942ApJ....96..161S Schönberg & Chandrasekhar (1942)] (see the above article excerpt) when the core obeys a polytropic equation of state. For example, in order to ensure that, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math> | |||

P(r_i)|_c = P(r_i)|_e \, , | |||

</math> | |||

</div> | |||

the expression for <math>P</math> given in the <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> column and ''evaluated at the interface'' is set equal to the expression for <math>P</math> given in the <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> column and ''evaluated at the interface''. This results in the <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> relation shown in the left-hand column of Table 2, namely, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math> | |||

K_c \rho_0^{1+1/n_c} \theta^{n_c + 1}_i = K_e \rho_e^{1+1/n_e} \phi^{n_e + 1}_i \, . | |||

</math> | |||

</div> | |||

Likewise, in order to ensure that, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math> | |||

M_r(r_i)|_c = M_r(r_i)|_e \, , | |||

</math> | |||

</div> | |||

the expression for <math>M_r</math> given in the <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> column of Table 1 and ''evaluated at the interface'' is set equal to the expression for <math>M_r</math> given in the <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> column of Table 1 and ''evaluated at the interface''. This results in the <math>4^\mathrm{th}</math> relation shown in the left-hand column of Table 2. The <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> relation shown in the left-hand column of Table 2 ensures that the dimensionless coordinate used to identify the surface of the core, <math>\xi_i</math>, and the dimensionless coordinate used to identify the base of the envelope, <math>\eta_i</math>, refer to exactly the same physical (dimensional) radial location, <math>r_i</math>. It is obtained by setting the expression for <math>r</math> given in the <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> column of Table 1 and ''evaluated at the interface'' equal to the expression for <math>r</math> given in the <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> column of Table 1 and ''evaluated at the interface''. | |||

Finally, drawing on the expressions for <math>\rho</math> that are given in the <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> and <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> columns of Table 1, we note that the <math>1^\mathrm{st}</math> relation shown in the left-hand column of Table 2 ensures that, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math> | |||

\frac{\rho(r_i)}{\mu}\biggr|_c = \frac{\rho(r_i)}{\mu}\biggr|_e \, . | |||

</math> | |||

</div> | |||

This relation also ensures that, as desired, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math> | |||

T(r_i)|_c = T(r_i)|_e \, , | |||

</math> | |||

</div> | |||

if, as assumed by [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1942ApJ....96..161S Schönberg & Chandrasekhar (1942)] (again, see the above article excerpt), <math>T</math> is related to <math>P</math> and <math>\rho</math> through the ideal-gas equation of state. More specifically, according to the ideal-gas equation of state, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math> | |||

\frac{1}{T} = \biggl[ \frac{H}{kP} \biggr] \frac{\rho}{\mu} \, . | |||

</math> | |||

</div> | |||

Hence, if <math>P</math> is continuous across the interface, as has already been assured, then the continuity of <math>T</math> across the interface will be ensured by guaranteeing the continuity of <math>\rho/\mu</math> across the interface. | |||

| Line 331: | Line 401: | ||

<table border="1" cellpadding="5"> | <table border="1" cellpadding="5"> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="center" colspan=" | <td align="center" colspan="2"> | ||

<font size="+1"><b>Table 2:</b> Interface Conditions</font> | <font size="+1"><b>Table 2:</b> Interface Conditions</font> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="center" colspan=" | <td align="center" colspan="1"> | ||

<font size="+1" color="darkblue"> | <font size="+1" color="darkblue"> | ||

'''Core''' | '''Polytropic Core''' | ||

</font> | </font> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<font size="+1" color="darkblue"> | <font size="+1" color="darkblue"> | ||

''' | '''Isothermal Core''' | ||

</font> | </font> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

| Line 356: | Line 425: | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="right"> | <td align="right"> | ||

<math>\ | <math>\biggl( \frac{\rho_0}{\mu_c} \biggr) \theta^{n_c}_i</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

| Line 362: | Line 431: | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math>\ | <math>\biggl( \frac{\rho_e}{\mu_e} \biggr) \phi^{n_e}_i</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

| Line 368: | Line 437: | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="right"> | <td align="right"> | ||

<math> | <math>K_c \rho_0^{1+1/n_c} \theta^{n_c + 1}_i</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

| Line 374: | Line 443: | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math> | <math>K_e \rho_e^{1+1/n_e} \phi^{n_e + 1}_i</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

| Line 380: | Line 449: | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="right"> | <td align="right"> | ||

<math> | <math>\biggl[ \frac{(n_c + 1)K_c}{4\pi G} \biggr]^{1/2} \rho_0^{(1-n_c)/(2n_c)} \xi_i</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

| Line 386: | Line 455: | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math>\biggl[ \frac{ | <math>\biggl[ \frac{(n_e + 1)K_e}{4\pi G} \biggr]^{1/2} \rho_e^{(1-n_e)/(2n_e)} \eta_i</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

| Line 392: | Line 461: | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="right"> | <td align="right"> | ||

<math> | <math>[ (n_c + 1)K_c ]^{3/2} \rho_0^{(3-n_c)/(2n_c)} \biggl(\xi^2 \frac{d\theta}{d\xi} \biggr)_i</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

| Line 398: | Line 467: | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math> | <math>[ (n_e + 1)K_e ]^{3/2} \rho_e^{(3-n_e)/(2n_e)} \biggl(\eta^2 \frac{d\phi}{d\eta} \biggr)_i</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

| Line 407: | Line 476: | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<!-- BEGIN | <!-- BEGIN RIGHT BLOCK details --> | ||

<table border="0" cellpadding="3"> | <table border="0" cellpadding="3"> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="right"> | <td align="right"> | ||

<math>\biggl( \frac{\rho_0}{\mu_c} \biggr) | <math>\biggl( \frac{\rho_0}{\mu_c} \biggr) e^{-\psi_i}</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

| Line 417: | Line 486: | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math>\biggl( \frac{\rho_e}{\mu_e} \biggr) \phi^{n_e}</math> | <math>\biggl( \frac{\rho_e}{\mu_e} \biggr) \phi^{n_e}_i</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

| Line 423: | Line 492: | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="right"> | <td align="right"> | ||

<math> | <math>c_s^2 \rho_0 e^{-\psi_i}</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

| Line 429: | Line 498: | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math>K_e \rho_e^{1+1/n_e} \phi^{n_e + 1}</math> | <math>K_e \rho_e^{1+1/n_e} \phi^{n_e + 1}_i</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

| Line 435: | Line 504: | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="right"> | <td align="right"> | ||

<math>\biggl[ \frac{ | <math>\biggl[ \frac{c_s^2}{4\pi G\rho_0} \biggr]^{1/2} \chi_i</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

| Line 441: | Line 510: | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math>\biggl[ \frac{(n_e + 1)K_e}{4\pi G} \biggr]^{1/2} \rho_e^{(1-n_e)/(2n_e)} \ | <math>\biggl[ \frac{(n_e + 1)K_e}{4\pi G} \biggr]^{1/2} \rho_e^{(1-n_e)/(2n_e)} \eta_i</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

| Line 447: | Line 516: | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="right"> | <td align="right"> | ||

<math> | <math>\biggl[ \frac{c_s^6}{4\pi G^3\rho_0} \biggr]^{1/2} \biggl( \chi^2 \frac{d\psi}{d\chi} \biggr)_i</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

| Line 453: | Line 522: | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math>4\pi \biggl[ \frac{(n_e + 1)K_e}{4\pi G} \biggr]^{3/2} \rho_e^{(3-n_e)/(2n_e)} \biggl(-\eta^2 \frac{d\phi}{d\eta} \biggr)</math> | <math>4\pi \biggl[ \frac{(n_e + 1)K_e}{4\pi G} \biggr]^{3/2} \rho_e^{(3-n_e)/(2n_e)} \biggl(-\eta^2 \frac{d\phi}{d\eta} \biggr)_i</math> | ||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

<!-- END RIGHT BLOCK details --> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

After setting <math>\mu_c=\mu_e=1</math>, these four relations become identical to equations 482-485 (p. 172) of [[User:Tohline/Appendix/References#C67|[<b><font color="red">C67</font></b>]]]. | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

After setting <math>n_e = 1</math>, these four relations are essentially identical to, respectively, equations (13), (10), (12), & (11) of [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1988Ap%26SS.147..219B Beech 1988b]; adopting <math>n_e=3</math> instead, they serve as the foundation of earlier work by [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1941ApJ....94..525H Henrich & Chandraskhar (1941)]. | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

< | </div> | ||

<span id="TohlineGeneralization"> | |||

===The Tohline Generalization=== | |||

</span> | |||

[Introduced '''<font color="red">10 June 2013</font>'''] It should be pointed out that, while the interface conditions shown in Table 2 and the solution steps that follow do ensure that the gas pressure is continuous across the interface and allow for a discontinuity in the mass-density across the interface, they do not actually force the temperature to be continuous across the interface. More generally, pressure continuity is ensured if, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math> | |||

\frac{\rho(r_i)}{\mu/T(r_i)}\biggr|_c = \frac{\rho(r_i)}{\mu/T(r_i)}\biggr|_e \, . | |||

</math> | |||

</div> | |||

So a discontinuity across the interface will arise if the ratio of the molecular weights, <math>\mu_c/\mu_e</math>, is not unity, or if there is a discontinuity in the temperature across the interface — that is, if <math>T(r_i)|_e \ne T(r_i)|_c</math>, or both. Because they were using bipolytropes to model optically thick stellar interiors, [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1942ApJ....96..161S Schönberg & Chandrasekhar (1942)] argued that the temperature should also be continuous across the interface and, hence, that a discontinuity in the density would be introduced at the interface from a discontinuity in the molecular weight. [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/LimitingMasses#Relationship_Between_the_Bonnor-Ebert_and_Sch.C3.B6nberg-Chandrasekhar_Critical_Masses|In a separate chapter where we discuss the relationship between the Schönberg-Chandrasekhar critical mass and the Bonnor-Ebert critical mass]], we will argue that a discontinuous drop in the density is introduced by a substantial jump in the gas temperature at the interface. In making this alternate assumption, the structural equations describing the bipolytropic model will remain unchanged; we will only need to replace the ratio <math>\mu_c/\mu_e</math> by the ratio <math>T(r_i)|_e/T(r_i)|_c</math>. | |||

==Solution Steps== | |||

* Step 1: Choose <math>n_c</math> and <math>n_e</math>. | |||

* Step 2: Adopt boundary conditions at the center of the core (<math>\theta = 1</math> and <math>d\theta/d\xi = 0</math> at <math>\xi=0</math>), then solve the Lane-Emden equation to obtain the solution, <math>\theta(\xi)</math>, and its first derivative, <math>d\theta/d\xi</math> throughout the core; the radial location, <math>\xi = \xi_s</math>, at which <math>\theta(\xi)</math> first goes to zero identifies the natural surface of an [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/Polytropes#Lane-Emden_Equation|isolated polytrope]] that has a polytropic index <math>n_c</math>. | |||

* Step 3 Choose the desired location, <math>0 < \xi_i < \xi_s</math>, of the outer edge of the core. | |||

* Step 4: Specify <math>K_c</math> and <math>\rho_0</math>; the structural profile of, for example, <math>\rho(r)</math>, <math>P(r)</math>, and <math>M_r(r)</math> is then obtained throughout the core — over the radial range, <math>0 \le \xi \le \xi_i</math> and <math>0 \le r \le r_i</math> — via the relations shown in the <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> column of Table 1. | |||

* Step 5: Specify the ratio <math>\mu_e/\mu_c</math> and adopt the boundary condition, <math>\phi_i = 1</math>; then use the interface conditions as rearranged and presented in Table 3 to determine, respectively: | |||

** The gas density at the base of the envelope, <math>\rho_e</math>; | |||

** The polytropic constant of the envelope, <math>K_e</math>, relative to the polytropic constant of the core, <math>K_c</math>; | |||

** The ratio of the two dimensionless radial parameters at the interface, <math>\eta_i/\xi_i</math>; | |||

** The radial derivative of the envelope solution at the interface, <math>(d\phi/d\eta)_i</math>. | |||

* Step 6: The last sub-step of solution step 5 provides the boundary condition that is needed — in addition to our earlier specification that <math>\phi_i = 1</math> — to derive the desired ''particular'' solution, <math>\phi(\eta)</math>, of the Lane-Emden equation that is relevant throughout the envelope; knowing <math>\phi(\eta)</math> also provides the relevant structural first derivative, <math>d\phi/d\eta</math>, throughout the envelope. | |||

* Step 7: The surface of the bipolytrope will be located at the radial location, <math>\eta = \eta_s</math> and <math>r=R</math>, at which <math>\phi(\eta)</math> first drops to zero. | |||

* Step 8: The structural profile of, for example, <math>\rho(r)</math>, <math>P(r)</math>, and <math>M_r(r)</math> is then obtained throughout the envelope — over the radial range, <math>\eta_i \le \eta \le \eta_s</math> and <math>r_i \le r \le R</math> — via the relations provided in the <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> column of Table 1. | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="1" cellpadding="5"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center" colspan="2"> | |||

<font size="+1"><b>Table 3:</b> Sub-steps of Solution Step 5</font> <br> | |||

(derived from the relations in Table 2) | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center" colspan="1"> | |||

<font size="+1" color="darkblue"> | |||

'''Polytropic Core''' | |||

</font> | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

<font size="+1" color="darkblue"> | |||

'''Isothermal Core''' | |||

</font> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<!-- BEGIN | <tr> | ||

<td align="center"> | |||

<!-- BEGIN LEFT BLOCK details --> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="3"> | <table border="0" cellpadding="3"> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="right"> | <td align="right"> | ||

<math> | <math>\frac{\rho_e}{\rho_0}</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

| Line 472: | Line 603: | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math>\biggl( \frac{\ | <math>\biggl( \frac{\mu_e}{\mu_c} \biggr) \theta^{n_c}_i \phi_i^{-n_e}</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

| Line 478: | Line 609: | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="right"> | <td align="right"> | ||

<math> | <math>\biggl( \frac{K_e}{K_c} \biggr) \rho_0^{1/n_e - 1/n_c}</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

| Line 484: | Line 615: | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math> | <math>\biggl( \frac{\mu_e}{\mu_c} \biggr)^{-(1+1/n_e)} \theta^{1 - n_c/n_e}_i</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

| Line 490: | Line 621: | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="right"> | <td align="right"> | ||

<math> | <math>\frac{\eta_i}{\xi_i}</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

| Line 496: | Line 627: | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math>\biggl[ \frac{(n_e + 1) | <math>\biggl[ \frac{(n_c + 1)}{(n_e+1)} \biggr]^{1/2} \biggl( \frac{\mu_e}{\mu_c}\biggr) \theta_i^{(n_c-1)/2} \phi_i^{(1-n_e)/2}</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

| Line 502: | Line 633: | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="right"> | <td align="right"> | ||

<math> | <math>\biggl( \frac{d\phi}{d\eta} \biggr)_i</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | <td align="center"> | ||

| Line 508: | Line 639: | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="left"> | <td align="left"> | ||

<math> | <math>\biggl[ \frac{n_c + 1}{n_e + 1} \biggr]^{1/2} \theta_i^{- (n_c + 1)/2} \phi_i^{(n_e+1)/2} \biggl( \frac{d\theta}{d\xi} \biggr)_i</math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

<!-- END | <!-- END LEFT BLOCK details --> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

< | <td align="center"> | ||

<!-- BEGIN RIGHT BLOCK details --> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="3"> | |||

<table border=" | |||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align=" | <td align="right"> | ||

<td align="center"> | <math>\biggl( \frac{\rho_e}{\rho_0} \biggr)</math> | ||

<td align=" | </td> | ||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>\biggl( \frac{\mu_e}{\mu_c} \biggr) e^{-\psi_i} \phi_i^{-n_e}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align=" | <td align="right"> | ||

<math>\frac{K_e \rho_0^{1/n_e} }{c_s^2} </math> | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

<td align="center"><math> | <td align="center"> | ||

<td align=" | <math>=</math> | ||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>\biggl( \frac{\mu_e}{\mu_c} \biggr)^{-(1+1/n_e)} e^{+\psi_i/n_e} </math> | |||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align="center"><math>\ | <td align="right"> | ||

<math>\frac{\eta_i}{\chi_i}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>(n_e + 1)^{-1/2}\biggl( \frac{\mu_e}{\mu_c} \biggr) e^{-\psi_i/2} \phi_i^{(1-n_e)/2}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td align=" | <td align="right"> | ||

<math>- \biggl(\frac{d\phi}{d\eta} \biggr)_i</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>(n_e + 1)^{-1/2} e^{+\psi_i/2} \phi_i^{(n_e+1)/2} \biggl(\frac{d\psi}{d\chi} \biggr)_i</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

< | </table> | ||

<!-- END RIGHT BLOCK details --> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<span id="UVplane"> | |||

Taking the ratio of the <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> to <math>4^\mathrm{th}</math> expressions on the left-hand side of Table 3 produces,</span> | |||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

\frac{ | \frac{\eta_i \phi_i^{n_e}}{(d\phi/d\eta)_i} = \frac{\xi_i \theta_i^{n_c}}{(d\theta/d\xi)_i} \biggl( \frac{\mu_e}{\mu_c}\biggr) \, . | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

''Multiplying'' the <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> expression by the <math>4^\mathrm{th}</math> expression generates, | |||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

\ | (n_e+1)\frac{\eta_i (d\phi/d\eta)_i}{ \phi_i } = (n_c+1)\frac{\xi_i (d\theta/d\xi)_i}{ \theta_i } \biggl( \frac{\mu_e}{\mu_c}\biggr) \, . | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

These are two relations that Chandrasekhar found to be useful in his analysis of "composite [polytropic] configurations" — after setting <math>\mu_e=\mu_c</math> they match, respectively, equations 486 & 489 in § 28 of [[User:Tohline/Appendix/References#C67|[<b><font color="red">C67</font></b>]]]. | |||

==Isothermal Core== | |||

The relations shown in the right-hand columns of Table 2 and Table 3 provide analogous conditions that must be satisfied in order to ensure the proper continuity of physical parameters across the interface of a composite structure that has an isothermal, rather than a polytropic, core. The ''interface conditions'' shown in Table 2 were derived by properly associating the relations in the <math>1^\mathrm{st}</math> column of Table 1 with corresponding relations in the <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> column of Table 1. Strictly speaking, a structure whose core obeys an isothermal equation of state can also be considered a bipolytrope, but its mathematical description must be handled separately because its effective polytropic index is <math>n_c=\infty</math>. | |||

=Example Solutions= | |||

* [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/BiPolytropes/Analytic5_1#BiPolytrope_with_nc_.3D_5_and_ne_.3D_1|Analytic solution]] for <math>n_c = 5, ~n_e = 1</math>. | |||

* [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/BiPolytropes/Analytic0_0|Analytic solution]] for <math>n_c = 0, ~n_e = 0</math>. | |||

=Related Discussions= | |||

* [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/PolytropesEmbedded#Embedded_Polytropic_Spheres|Polytropes emdeded in an external medium]] | |||

* [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/BiPolytropes/Analytic5_1#BiPolytrope_with_nc_.3D_5_and_ne_.3D_1|Analytic description of BiPolytrope with <math>(n_c, n_e) = (5,1)</math>]] | |||

* [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/BonnorEbert#Pressure-Bounded_Isothermal_Sphere|Bonnor-Ebert spheres]] | |||

** [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bonnor-Ebert_mass Bonnor-Ebert Mass] according to Wikipedia | |||

** [http://www.astro.umd.edu/~cychen/MATLAB/ASTR320/matlabFrom320spring2011/Bonnor-EbertSphere/html/BonnorEbert.html A MATLAB script to determine the Bonnor-Ebert Mass coefficient] developed by [http://www.astro.umd.edu/people/cychen.html Che-Yu Chen] as a graduate student in the University of Maryland Department of Astronomy | |||

* [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/LimitingMasses#Sch.C3.B6nberg-Chandrasekhar_Mass|Schönberg-Chandrasekhar limiting mass]] | |||

* [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/LimitingMasses#Relationship_Between_the_Bonnor-Ebert_and_Sch.C3.B6nberg-Chandrasekhar_Critical_Masses|Relationship between Bonnor-Ebert and Schönberg-Chandrasekhar limiting masses]] | |||

* [http://www.researchgate.net/publication/2228492_Low_order_p-modes_in_a_bipolytropic_model_of_the_Sun Oscillations in a BiPolytropic Model of the Sun] | |||

* [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1988Ap%26SS.147..219B Schoenberg-Chandrasekhar Limit: A BiPolytropic Approximation (Beech 1988b)] | |||

* [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1988Ap%26SS.146..299B BiPolytropic Model for Low-Mass Stars (Beech 1988a)] | |||

* An analysis (published in French) of the secular stability of configurations containing an isothermal core, with relevance to the Schönberg-Chandrasekhar mass limit; [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1967AnAp...30..975G M. Gabriel and P. Ledoux (1967, Annals d'Astrophysique, 30, 975)] | |||

=See Also= | |||

* [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1983ApJ...275..713R Rappaport, Verbunt, & Joss (1983, ApJ, 275, 713)] — ''A New Technique for Calculations of Binary Stellar Evolution, with Application to Magnetic Braking''. | |||

{{LSU_HBook_footer}} | {{LSU_HBook_footer}} | ||

Latest revision as of 22:54, 22 May 2019

BiPolytropes

|

|---|

| | Tiled Menu | Tables of Content | Banner Video | Tohline Home Page | |

Background

While polytropic spheres can give us useful general insight into the internal structure of stars, they do not faithfully represent the detailed structure of most stars, in part, because the equation of state that is most relevant to the densest regions of a star usually is different from the equation of state that is relevant to the star's envelope. As is highlighted in the following excerpt from Cowling (1931), Milne (1930) was among the first to suggest that more realism could be achieved by constructing what is now commonly referred to as a bipolytrope: a composite model in which the envelope, obeying one equation of state — described by polytropic index <math>n_e</math> — is fitted to a core obeying a different equation of state — described by polytropic index <math>n_c</math>.

|

Text extracted† from p. 472 of T. G. Cowling (1931)

"Note on the Fitting of Polytropic Models in the Theory of Stellar Structure"

MNRAS, 91, 472-478 © Royal Astronomical Society |

| †Text displayed here, as a single digital image, with presentation order & layout modified from the original publication. |

Milne (1930) envisioned that the temperature, <math>~T</math>, and pressure, <math>~P</math>, should be "continuous across the surface of fit." Given that <math>~T</math> and <math>~P</math> are continuous, he envisioned that the gas density, <math>~\rho</math>, should be continuous across the surface of fit as well. Schönberg & Chandrasekhar (1942) later pointed out — see the following journal article excerpt — that, if the core and envelope have different molecular weights, it is the ratio <math>~\rho</math>/<math>~\bar{\mu}</math> that should be continuous across the interface. A discontinuous jump in <math>~\bar{\mu}</math> at the interface — for example, switching from a pure helium core to an envelope whose dominant element is hydrogen — will therefore lead to a discontinuous jump in <math>~\rho</math> at the interface.

|

Text excerpts† from §2 (pp. 161-162) of Schönberg & Chandrasekhar (1942)

"On the Evolution of the Main-Sequence Stars"

ApJ, 96, 161-172 © American Astronomicall Society |

| †Text displayed here, as a single digital image, with presentation order & layout modified from the original publication. |

Schönberg & Chandrasekhar (1942) furthermore pointed out — again, see the relevant article excerpt — that, when constructing a bipolytropic model, the mathematical function that specifies the mass enclosed inside a spherical radius <math>r</math> for the core, <math>M(r)|_\mathrm{c}</math>, must give the same value as the mathematical function that specifies the mass enclosed inside a spherical radius <math>r</math> for the envelope, <math>M(r)|_\mathrm{e}</math> at the radial location of the interface, <math>r_i</math>.

Setup

Here we lay the mathematical foundation for building a spherically symmetric structure in which the core and the envelope are described by different barotropic equations of state. The <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> and <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> columns of Table 1 provide the relevant set of relations for a structure in which the core and envelope obey polytropic equations of state that have, respectively, polytropic indexes <math>n_c</math> and <math>n_e</math>. Drawing on our related discussion of isolated polytropes, it is clear that the structural profile in both regions should be given by a solution of the

Lane-Emden Equation

|

<math>~\frac{1}{\xi^2} \frac{d}{d\xi}\biggl( \xi^2 \frac{d\Theta_H}{d\xi} \biggr) = - \Theta_H^n</math> |

If either region is governed by an isothermal, rather than polytropic, equation of state then, as we have discussed in the context of both isolated and pressure-bounded isothermal spheres and as is shown by equation (374) of [C67], the structural profile should be given instead by a solution of the related equation,

<math> \frac{1}{\chi^2} \frac{d}{d\chi} \biggl( \chi^2 \frac{d\psi}{d\chi} \biggr) = e^{-\psi} \, . </math>

The <math>1^\mathrm{st}</math> column of Table 1 provides the relevant set of associated structural relations for an isothermal core.

|

Table 1: Setup |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Core: Choose isothermal equation of state or polytropic index <math>n_c</math> |

Envelope |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Isothermal <math>(n_c = \infty)</math> |

<math>n = n_c</math> |

<math>n = n_e</math> |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

<math> \frac{1}{\chi^2} \frac{d}{d\chi} \biggl( \chi^2 \frac{d\psi}{d\chi} \biggr) = e^{-\psi} </math> sol'n: <math> \psi(\chi) </math> |

<math> \frac{1}{\xi^2} \frac{d}{d\xi} \biggl( \xi^2 \frac{d\theta}{d\xi} \biggr) = - \theta^{n_c} </math> sol'n: <math> \theta(\xi) </math> |

<math> \frac{1}{\eta^2} \frac{d}{d\eta} \biggl( \eta^2 \frac{d\phi}{d\eta} \biggr) = - \phi^{n_e} </math> sol'n: <math> \phi(\eta) </math> |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

NOTE typed on 13 May 2019: Prior to this date, in both the middle and right-hand colums, the RHS of the polytropic version of the Lane-Emden equation incorrectly had a positive sign. This was a type-setting error that has now been corrected. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Polytropic Core

Using the notation established in Table 1, if the core obeys a polytropic equation of state, the variable <math>\xi</math> will denote the dimensionless radial coordinate through the core and the relevant solution is a function, <math>\theta(\xi)</math>, whose value goes to <math>1</math> and whose first derivative, <math>d\theta/d\xi</math>, goes to <math>0</math> at <math>\xi = 0</math>. Then, given a value of the central density, <math>\rho_0</math>, the density throughout the core is,

<math>\rho(\xi) = \rho_0 \theta(\xi)^{n_c}</math> ;

and, given a value of the polytropic constant in the core, <math>K_c</math>, the pressure throughout the core is,

<math>P(\xi) = K_c \rho_0^{1+1/n_c} \theta(\xi)^{n_c + 1}</math>.

Likewise, given <math>\rho_0</math> and <math>K_c</math>, the radial coordinate <math>r</math> (in dimensional rather than dimensionless units) and the mass enclosed within this radius, <math>M_r</math>, are given by the bottom two expressions shown in the <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> column of Table 1.

The structure of an isolated polytrope would be described by following the function <math>\theta(\xi)</math> all the way out to the surface, that is, to the radial location <math>\xi_\mathrm{surf}</math> where <math>\theta(\xi)</math> first drops to zero. (Analytic solutions of this type are presented elsewhere for <math>n = 0</math>, <math>n = 1</math>, and <math>n = 5</math>.) In constructing a bipolytrope, we will instead follow <math>\theta(\xi)</math> out to a radius <math>\xi_i < \xi_\mathrm{surf}</math>, then build an envelope whose inner radius — or base — is at the interface radius, <math>r_i</math>, that corresponds to <math>\xi_i</math>. For any choice of the pair of polytropic indexes, <math>n_c</math> and <math>n_e</math>, a series of bipolytropes can then be constructed by choosing a variety of different interface radii.

Polytropic Envelope

Again following the notation of Table 1, we will use <math>\eta</math> to identify the dimensionless radial coordinate through the envelope, and the relevant solution of the Lane-Emden equation will be the function, <math>\phi(\eta)</math>. The particular solution that we seek for the envelope will differ from the solution obtained in the core not only because the governing polytropic index is different but also because the envelope solution will be constrained by different boundary conditions: The value of the function <math>\phi(\eta)</math> as well as its first derivative, <math>d\phi/d\eta</math>, must be specified at some radial location within the envelope. Because the envelope does not extend all the way to the center of the structure, it makes more sense to choose a solution in which <math>\phi</math> is set to unity at the inner edge of the envelope — that is, at the radial location <math>\eta_i</math> that corresponds to <math>r_i</math> — rather than at <math>\eta = 0</math>. By setting <math>\phi = 1</math> at the base of the envelope, it should be clear from the expression,

<math> \rho = \rho_e \phi^{n_e} \, , </math>

(taken from the <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> column of Table 1) that <math>\rho_e</math> represents the value of the gas density at the base of the envelope. The value of <math>\rho_e</math> can be obtained from knowledge of the gas density at the outer edge of the core (i.e., at <math>r_i</math>) combined with the specified molecular-weight jump condition at the interface. Looking ahead at the first interface condition for a polytropic core catalogued in Table 2, we see more specifically that, after setting <math>\phi_i = 1</math>,

<math> \rho_e = \rho_0 \biggl( \frac{\mu_e}{\mu_c} \biggr) \theta^{n_c}_i \, . </math>

As we will show in connection with Table 3, the value of <math>d\phi/d\eta</math> at the base of the envelope (i.e., at <math>r_i</math>) also will be set by the properties of the core at the interface — specifically, by the values of <math>(d\theta/d\xi)_i</math> and <math>\theta_i</math>.

Interface Conditions

The Schönberg-Chandrasekhar Condition

The <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> and <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> columns of Table 1 provide the mathematical relations that are needed to implement the interface matching conditions specified by equation (1) of Schönberg & Chandrasekhar (1942) (see the above article excerpt) when the core obeys a polytropic equation of state. For example, in order to ensure that,

<math> P(r_i)|_c = P(r_i)|_e \, , </math>

the expression for <math>P</math> given in the <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> column and evaluated at the interface is set equal to the expression for <math>P</math> given in the <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> column and evaluated at the interface. This results in the <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> relation shown in the left-hand column of Table 2, namely,

<math> K_c \rho_0^{1+1/n_c} \theta^{n_c + 1}_i = K_e \rho_e^{1+1/n_e} \phi^{n_e + 1}_i \, . </math>

Likewise, in order to ensure that,

<math> M_r(r_i)|_c = M_r(r_i)|_e \, , </math>

the expression for <math>M_r</math> given in the <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> column of Table 1 and evaluated at the interface is set equal to the expression for <math>M_r</math> given in the <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> column of Table 1 and evaluated at the interface. This results in the <math>4^\mathrm{th}</math> relation shown in the left-hand column of Table 2. The <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> relation shown in the left-hand column of Table 2 ensures that the dimensionless coordinate used to identify the surface of the core, <math>\xi_i</math>, and the dimensionless coordinate used to identify the base of the envelope, <math>\eta_i</math>, refer to exactly the same physical (dimensional) radial location, <math>r_i</math>. It is obtained by setting the expression for <math>r</math> given in the <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> column of Table 1 and evaluated at the interface equal to the expression for <math>r</math> given in the <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> column of Table 1 and evaluated at the interface.

Finally, drawing on the expressions for <math>\rho</math> that are given in the <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> and <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> columns of Table 1, we note that the <math>1^\mathrm{st}</math> relation shown in the left-hand column of Table 2 ensures that,

<math> \frac{\rho(r_i)}{\mu}\biggr|_c = \frac{\rho(r_i)}{\mu}\biggr|_e \, . </math>

This relation also ensures that, as desired,

<math> T(r_i)|_c = T(r_i)|_e \, , </math>

if, as assumed by Schönberg & Chandrasekhar (1942) (again, see the above article excerpt), <math>T</math> is related to <math>P</math> and <math>\rho</math> through the ideal-gas equation of state. More specifically, according to the ideal-gas equation of state,

<math> \frac{1}{T} = \biggl[ \frac{H}{kP} \biggr] \frac{\rho}{\mu} \, . </math>

Hence, if <math>P</math> is continuous across the interface, as has already been assured, then the continuity of <math>T</math> across the interface will be ensured by guaranteeing the continuity of <math>\rho/\mu</math> across the interface.

|

Table 2: Interface Conditions |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Polytropic Core |

Isothermal Core |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

After setting <math>\mu_c=\mu_e=1</math>, these four relations become identical to equations 482-485 (p. 172) of [C67]. |

After setting <math>n_e = 1</math>, these four relations are essentially identical to, respectively, equations (13), (10), (12), & (11) of Beech 1988b; adopting <math>n_e=3</math> instead, they serve as the foundation of earlier work by Henrich & Chandraskhar (1941). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Tohline Generalization

[Introduced 10 June 2013] It should be pointed out that, while the interface conditions shown in Table 2 and the solution steps that follow do ensure that the gas pressure is continuous across the interface and allow for a discontinuity in the mass-density across the interface, they do not actually force the temperature to be continuous across the interface. More generally, pressure continuity is ensured if,

<math> \frac{\rho(r_i)}{\mu/T(r_i)}\biggr|_c = \frac{\rho(r_i)}{\mu/T(r_i)}\biggr|_e \, . </math>

So a discontinuity across the interface will arise if the ratio of the molecular weights, <math>\mu_c/\mu_e</math>, is not unity, or if there is a discontinuity in the temperature across the interface — that is, if <math>T(r_i)|_e \ne T(r_i)|_c</math>, or both. Because they were using bipolytropes to model optically thick stellar interiors, Schönberg & Chandrasekhar (1942) argued that the temperature should also be continuous across the interface and, hence, that a discontinuity in the density would be introduced at the interface from a discontinuity in the molecular weight. In a separate chapter where we discuss the relationship between the Schönberg-Chandrasekhar critical mass and the Bonnor-Ebert critical mass, we will argue that a discontinuous drop in the density is introduced by a substantial jump in the gas temperature at the interface. In making this alternate assumption, the structural equations describing the bipolytropic model will remain unchanged; we will only need to replace the ratio <math>\mu_c/\mu_e</math> by the ratio <math>T(r_i)|_e/T(r_i)|_c</math>.

Solution Steps

- Step 1: Choose <math>n_c</math> and <math>n_e</math>.

- Step 2: Adopt boundary conditions at the center of the core (<math>\theta = 1</math> and <math>d\theta/d\xi = 0</math> at <math>\xi=0</math>), then solve the Lane-Emden equation to obtain the solution, <math>\theta(\xi)</math>, and its first derivative, <math>d\theta/d\xi</math> throughout the core; the radial location, <math>\xi = \xi_s</math>, at which <math>\theta(\xi)</math> first goes to zero identifies the natural surface of an isolated polytrope that has a polytropic index <math>n_c</math>.

- Step 3 Choose the desired location, <math>0 < \xi_i < \xi_s</math>, of the outer edge of the core.

- Step 4: Specify <math>K_c</math> and <math>\rho_0</math>; the structural profile of, for example, <math>\rho(r)</math>, <math>P(r)</math>, and <math>M_r(r)</math> is then obtained throughout the core — over the radial range, <math>0 \le \xi \le \xi_i</math> and <math>0 \le r \le r_i</math> — via the relations shown in the <math>2^\mathrm{nd}</math> column of Table 1.

- Step 5: Specify the ratio <math>\mu_e/\mu_c</math> and adopt the boundary condition, <math>\phi_i = 1</math>; then use the interface conditions as rearranged and presented in Table 3 to determine, respectively:

- The gas density at the base of the envelope, <math>\rho_e</math>;

- The polytropic constant of the envelope, <math>K_e</math>, relative to the polytropic constant of the core, <math>K_c</math>;

- The ratio of the two dimensionless radial parameters at the interface, <math>\eta_i/\xi_i</math>;

- The radial derivative of the envelope solution at the interface, <math>(d\phi/d\eta)_i</math>.

- Step 6: The last sub-step of solution step 5 provides the boundary condition that is needed — in addition to our earlier specification that <math>\phi_i = 1</math> — to derive the desired particular solution, <math>\phi(\eta)</math>, of the Lane-Emden equation that is relevant throughout the envelope; knowing <math>\phi(\eta)</math> also provides the relevant structural first derivative, <math>d\phi/d\eta</math>, throughout the envelope.

- Step 7: The surface of the bipolytrope will be located at the radial location, <math>\eta = \eta_s</math> and <math>r=R</math>, at which <math>\phi(\eta)</math> first drops to zero.

- Step 8: The structural profile of, for example, <math>\rho(r)</math>, <math>P(r)</math>, and <math>M_r(r)</math> is then obtained throughout the envelope — over the radial range, <math>\eta_i \le \eta \le \eta_s</math> and <math>r_i \le r \le R</math> — via the relations provided in the <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> column of Table 1.

|

Table 3: Sub-steps of Solution Step 5 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Polytropic Core |

Isothermal Core |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Taking the ratio of the <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> to <math>4^\mathrm{th}</math> expressions on the left-hand side of Table 3 produces,

<math> \frac{\eta_i \phi_i^{n_e}}{(d\phi/d\eta)_i} = \frac{\xi_i \theta_i^{n_c}}{(d\theta/d\xi)_i} \biggl( \frac{\mu_e}{\mu_c}\biggr) \, . </math>

Multiplying the <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> expression by the <math>4^\mathrm{th}</math> expression generates,

<math> (n_e+1)\frac{\eta_i (d\phi/d\eta)_i}{ \phi_i } = (n_c+1)\frac{\xi_i (d\theta/d\xi)_i}{ \theta_i } \biggl( \frac{\mu_e}{\mu_c}\biggr) \, . </math>

These are two relations that Chandrasekhar found to be useful in his analysis of "composite [polytropic] configurations" — after setting <math>\mu_e=\mu_c</math> they match, respectively, equations 486 & 489 in § 28 of [C67].

Isothermal Core

The relations shown in the right-hand columns of Table 2 and Table 3 provide analogous conditions that must be satisfied in order to ensure the proper continuity of physical parameters across the interface of a composite structure that has an isothermal, rather than a polytropic, core. The interface conditions shown in Table 2 were derived by properly associating the relations in the <math>1^\mathrm{st}</math> column of Table 1 with corresponding relations in the <math>3^\mathrm{rd}</math> column of Table 1. Strictly speaking, a structure whose core obeys an isothermal equation of state can also be considered a bipolytrope, but its mathematical description must be handled separately because its effective polytropic index is <math>n_c=\infty</math>.

Example Solutions

- Analytic solution for <math>n_c = 5, ~n_e = 1</math>.

- Analytic solution for <math>n_c = 0, ~n_e = 0</math>.

Related Discussions

- Polytropes emdeded in an external medium

- Analytic description of BiPolytrope with <math>(n_c, n_e) = (5,1)</math>

- Bonnor-Ebert spheres

- Bonnor-Ebert Mass according to Wikipedia

- A MATLAB script to determine the Bonnor-Ebert Mass coefficient developed by Che-Yu Chen as a graduate student in the University of Maryland Department of Astronomy

- Schönberg-Chandrasekhar limiting mass

- Relationship between Bonnor-Ebert and Schönberg-Chandrasekhar limiting masses

- Oscillations in a BiPolytropic Model of the Sun

- Schoenberg-Chandrasekhar Limit: A BiPolytropic Approximation (Beech 1988b)

- BiPolytropic Model for Low-Mass Stars (Beech 1988a)

- An analysis (published in French) of the secular stability of configurations containing an isothermal core, with relevance to the Schönberg-Chandrasekhar mass limit; M. Gabriel and P. Ledoux (1967, Annals d'Astrophysique, 30, 975)

See Also

- Rappaport, Verbunt, & Joss (1983, ApJ, 275, 713) — A New Technique for Calculations of Binary Stellar Evolution, with Application to Magnetic Braking.

|

|---|

|

© 2014 - 2021 by Joel E. Tohline |