Difference between revisions of "User:Tohline/Apps/DysonPotential"

| Line 1,993: | Line 1,993: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

<table border="1" align="center" cellpadding="8"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<th align="center">Contour<br />Column #</th> | |||

<th align="center"><math>~V_2</math> (external)</th> | |||

<th align="center">Surface <math>~\varpi</math></th> | |||

<th align="center"><math>~\chi</math> (radians)</th> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center">red (5)</td> | |||

<td align="right">0.9800</td> | |||

<td align="right">0.867</td> | |||

<td align="right">1.2318</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center">light green (6)</td> | |||

<td align="right">0.9800</td> | |||

<td align="right">0.838</td> | |||

<td align="right">1.1538</td> | |||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

Revision as of 18:03, 1 September 2018

Dyson (1893)

|

|---|

| | Tiled Menu | Tables of Content | Banner Video | Tohline Home Page | |

Overview

In his pioneering work, F. W. Dyson (1893a, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. A., 184, 43 - 95) and (1893b, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. A., 184, 1041 - 1106) used analytic techniques to determine the approximate equilibrium structure of axisymmetric, uniformly rotating, incompressible tori. C.-Y. Wong (1974, ApJ, 190, 675 - 694) extended Dyson's work, using numerical techniques to obtain more accurate — but still approximate — equilibrium structures for incompressible tori having solid body rotation. Since then, Y. Eriguchi & D. Sugimoto (1981, Progress of Theoretical Physics, 65, 1870 - 1875) and I. Hachisu, J. E. Tohline & Y. Eriguchi (1987, ApJ, 323, 592 - 613) have mapped out the full sequence of Dyson-Wong tori, beginning from a bifurcation point on the Maclaurin spheroid sequence.

External Potential

His Derived Expression

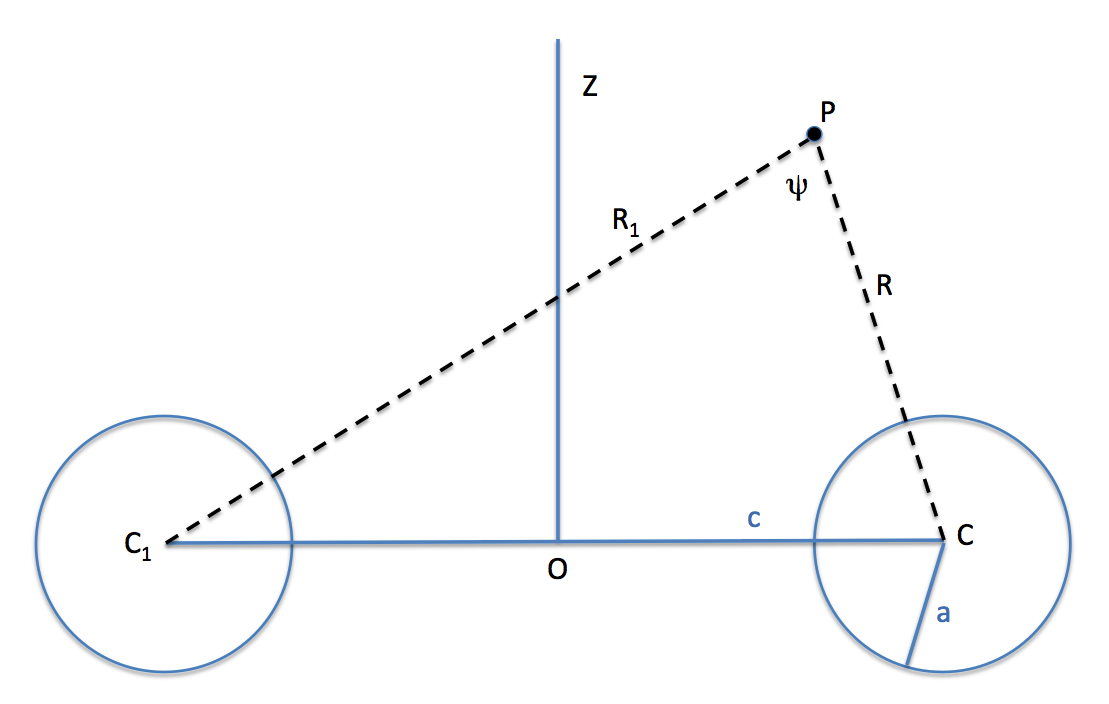

On p. 62 of Dyson (1893a), we find the following approximate expression for the potential at point "P", anywhere exterior to an anchor ring:

|

|

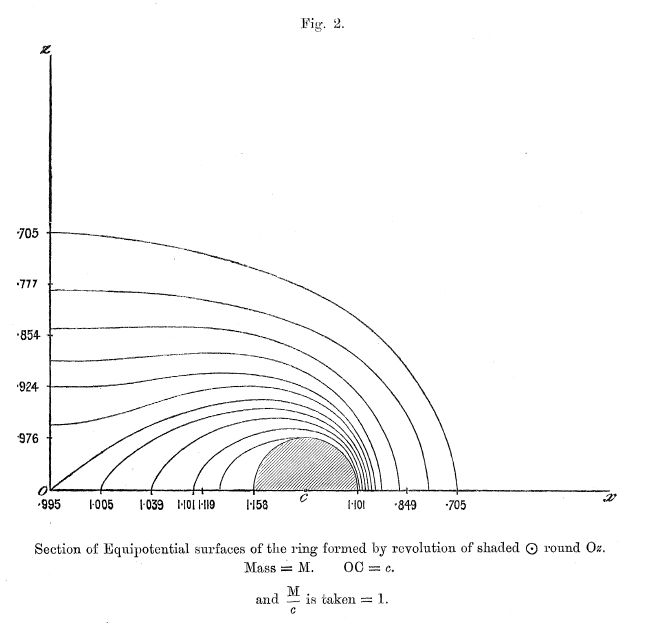

Equation image extracted without modification from p. 62 of Dyson (1893a)

The Potential of an Anchor Ring, Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. London. A., Vol. 184 |

In Dyson's expression, the leading factor of <math>~F</math> is the complete elliptic integral of the first kind, namely,

|

<math>~F = F(\mu)</math> |

<math>~\equiv</math> |

<math>~\int_0^{\pi/2} \frac{d\phi}{\sqrt{1 - \mu^2 \sin^2\phi}} \, ,</math> |

where, <math>~\mu \equiv (R_1 - R)/(R_1 + R)</math>. Similarly, <math>~E = E(\mu)</math> is the complete elliptic integral of the second kind.

Comparison With Thin Ring Approximation

In the limit of <math>~a/c \rightarrow 0</math>, Dyson's expression gives,

|

<math>~V_\mathrm{Dyson}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{4K(\mu)}{R+R_1} \, ,</math> |

where we have acknowledged that, in the twenty-first century, the complete elliptic integral of the first kind is more customarily represented by the letter, <math>~K</math>. In a separate discussion, we have shown that the gravitational potential of an infinitesimally thin ring is given precisely by the expression,

|

<math>~\biggl[ \frac{\pi}{GM}\biggr] \Phi_\mathrm{TR}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~- \frac{2K(k)}{R_1} \, ,</math> |

where, <math>~k \equiv [1-(R/R_1)^2]^{1 / 2}</math>. Is Dyson's expression identical to this one when <math>~a/c = 0</math> ?

Proof

Taking a queue from our accompanying discussion of toroidal coordinates, if we adopt the variable notation,

<math>~\eta \equiv \ln\biggl(\frac{R_1}{R}\biggr) \, ,</math>

then we can write,

|

<math>~\cosh\eta = \frac{1}{2}\biggl[e^\eta + e^{-\eta}\biggr]</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{R^2 + R_1^2}{2RR_1} \, ,</math> |

which implies that,

|

<math>~\biggl[ \frac{2}{\coth\eta +1} \biggr]^{1 / 2} = [1 - e^{-2\eta}]^{1 / 2}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl[ 1 - \biggl(\frac{R}{R_1}\biggr)^2 \biggr]^{1 / 2} \, .</math> |

This is the definition of the parameter, <math>~k</math>, in the expression for <math>~\Phi_\mathrm{TR}</math>. Now, if we employ the Descending Landen Transformation for the complete elliptic integral of the first kind, we can make the substitution,

|

<math>~K(k)</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ (1 + k_1)K(k_1) \, , </math> |

where, |

<math>~k_1</math> |

<math>~\equiv</math> |

<math>~ \frac{1-\sqrt{1-k^2}}{1+\sqrt{1-k^2}} \, . </math> |

But notice that, <math>~\sqrt{1-k^2} = e^{-\eta}</math>, in which case,

|

<math>~k_1 </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ \frac{1-e^{-\eta}}{1+e^{-\eta}} </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ \frac{1-R/R_1}{1+R/R_1} </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ \frac{R_1-R}{R_1+R} \, , </math> |

which is the definition of the parameter, <math>~\mu</math>, in the expression for <math>~V_\mathrm{Dyson}</math>. Hence, we can write,

|

<math>~\biggl[ \frac{\pi}{GM}\biggr] \Phi_\mathrm{TR}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~- \frac{2}{R_1} \biggl[(1+k_1)K(k_1) \biggr] </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~- \frac{2K(\mu)}{R_1} \biggl[1+\frac{R_1-R}{R_1+R} \biggr] </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~- \frac{4K(\mu)}{R_1+R} \, .</math> |

Aside from the adopted sign convention, this is indeed precisely the expression given by <math>~V_\mathrm{Dyson}</math> when <math>~a/c = 0</math> .

Evaluation

Dyson's Figures

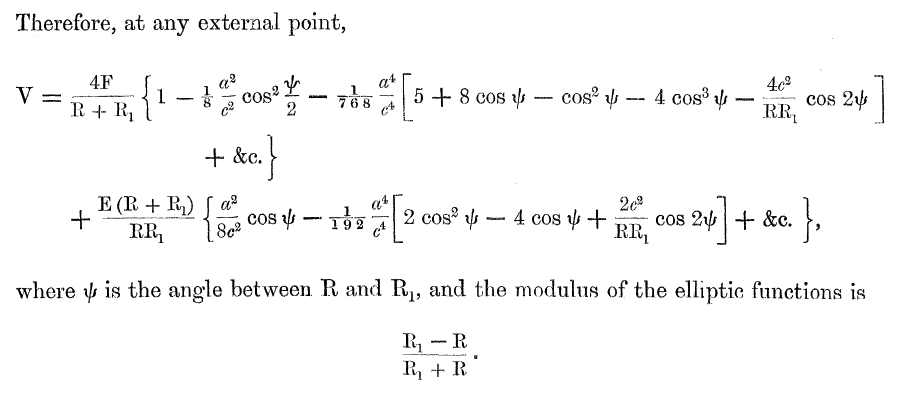

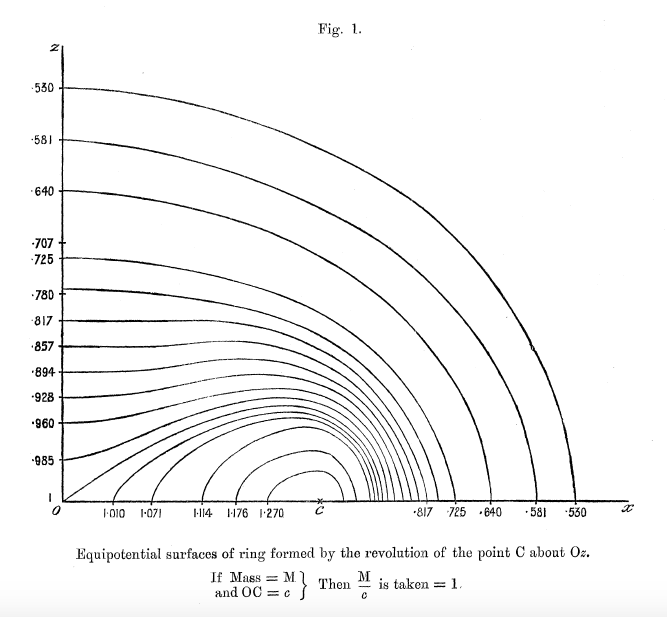

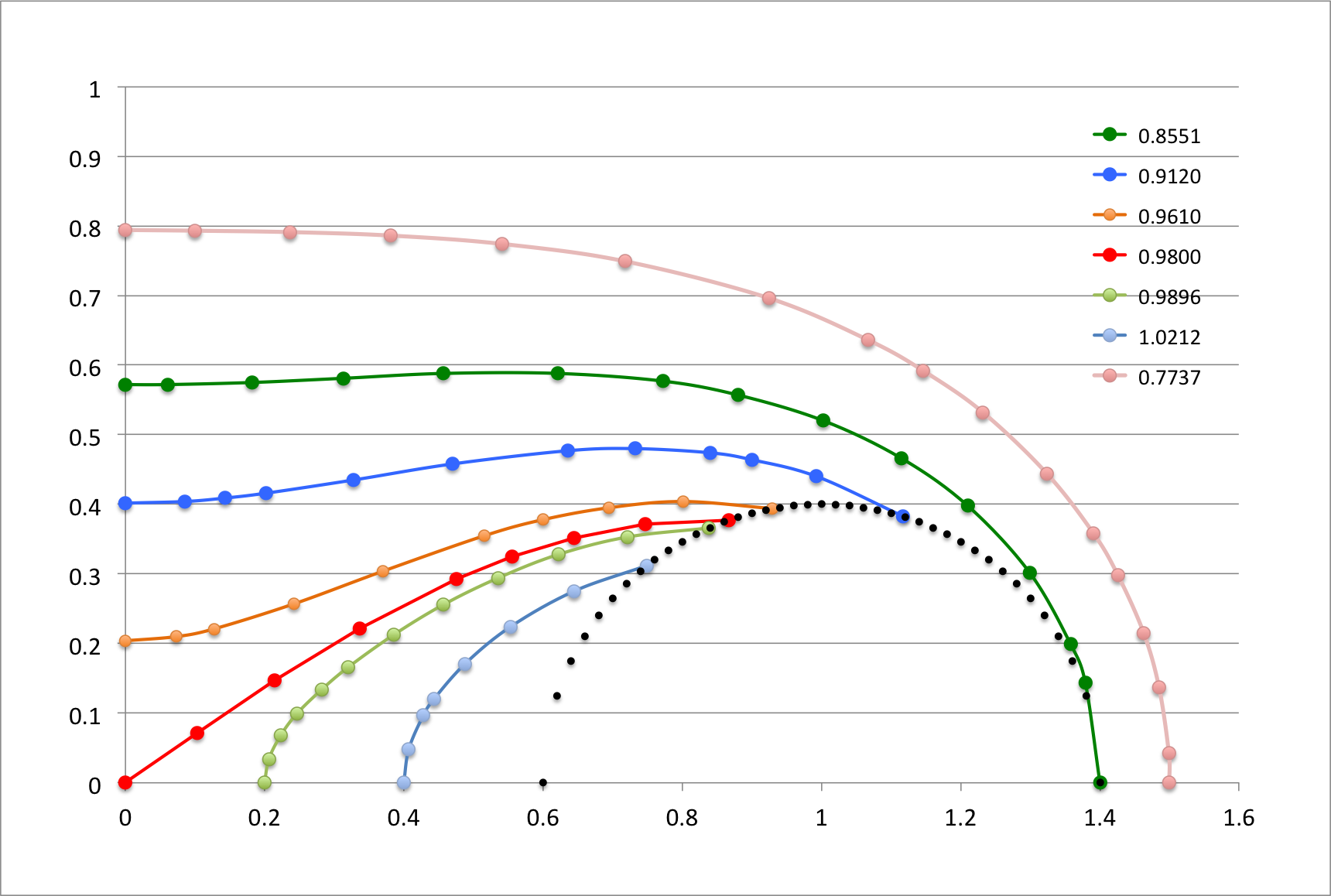

In his effort to illustrate the behavior of equipotential contours in the space exterior to various anchor rings, Dyson evaluated his expression for the potential up through <math>~\mathcal{O}(\tfrac{a^2}{c^2})</math>; that is, he evaluated the function,

|

<math>~V_2 \equiv V_\mathrm{Dyson}\biggr|_{\mathcal{O}(a^2/c^2)}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ \frac{4K(\mu)}{R+R_1}\biggl[1 - \frac{1}{8}\biggl(\frac{a^2}{c^2}\biggr) \cos^2\biggl( \frac{\psi}{2}\biggr)\biggr] + \frac{(R + R_1)E(\mu)}{RR_1}\biggl[\frac{1}{8}\biggl(\frac{a^2}{c^2}\biggr) \cos\psi \biggr] \, . </math> |

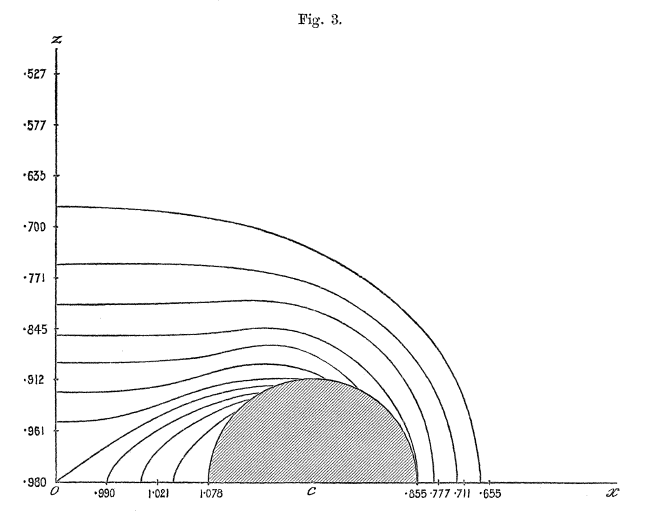

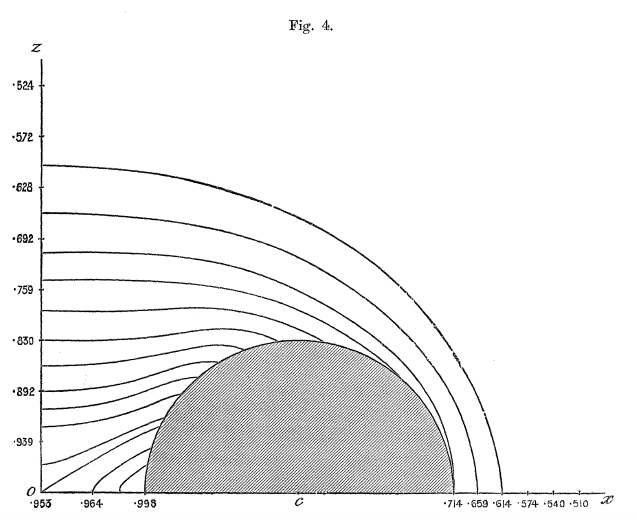

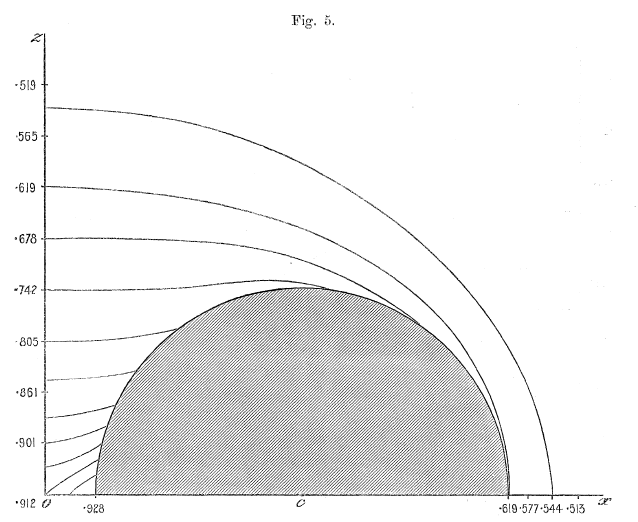

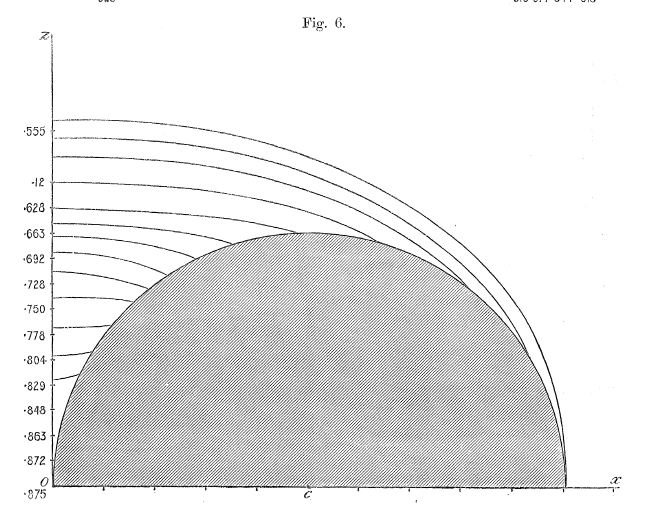

Figures 1 - 6 from Dyson (1893a) — replicated immediately below — show his resulting set of contours for six cases: Tori (anchor rings) having aspect ratios of <math>~a/c = 0, 1/5, 2/5, 3/5, 4/5, 1</math>. Click on an image to view the contour plot at higher resolution. In what follows we present results from our own evaluation of this "V2" function for the single case of an anchor ring having <math>~a/c = 2/5</math>.

| |||||||||

Our Attempt to Replicate

First, let's test the accuracy of Dyson's (1893a) "series expansion" expression for the elliptic integrals, <math>~K(\mu)</math> and <math>~E(\mu)</math>; in the following table, the high-precision evaluations labeled "Numerical Recipes" have been drawn from the tabulated data that is provided in our accompanying discussion of incomplete elliptic integrals. According to, for example, Wikipedia, the relevant series-expansion expressions are:

|

<math>~K(\mu)</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ \frac{\pi}{2} \biggl\{ 1 + \biggl[\frac{1}{2}\biggr]^2\mu^2 + \biggl[ \frac{1\cdot 3}{2\cdot 4}\biggr]^2\mu^4 + \biggl[ \frac{5\cdot 3\cdot 1}{6\cdot 4\cdot 2} \biggr]^2 \mu^6 + \cdots + \biggl[ \frac{(2n-1)!!}{(2n)!!}\biggr]^2 \mu^{2n} +\cdots \biggr\} \, ; </math> |

|

<math>~E(\mu)</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ \frac{\pi}{2} \biggl\{ 1 ~-~ \biggl[\frac{1}{2}\biggr]^2\frac{\mu^2}{1} ~-~ \biggl[ \frac{1\cdot 3}{2\cdot 4}\biggr]^2 \frac{\mu^4}{3} ~- ~\biggl[ \frac{5\cdot 3\cdot 1}{6\cdot 4\cdot 2} \biggr]^2 \frac{\mu^6}{5} ~- ~\cdots ~- ~\biggl[ \frac{(2n-1)!!}{(2n)!!}\biggr]^2 \frac{\mu^{2n}}{2n-1} ~-~ \cdots \biggr\} \, . </math> |

These expressions — up through <math>~\mathcal{O}(\mu^4)</math> — can be found in the middle of p. 58 of Dyson (1893a). We strongly suspect that, in constructing the equipotential contours shown in his figures 1-6, Dyson used expressions for <math>~K(\mu)</math> and <math>~E(\mu)</math> that were more accurate than this. For example, we found it necessary to include terms up through <math>~\mathcal{O}(\mu^{10})</math> in order to match to three digits accuracy the potential contour values and coordinate locations reported by Dyson.

| <math>~\mu</math> | Numerical Recipes | Series expansion up through <math>~\mathcal{O}(\mu^4)</math> | Series expansion up through <math>~\mathcal{O}(\mu^{10})</math> | |||

| <math>~K(\mu)</math> | <math>~E(\mu)</math> | <math>~K(\mu)</math> | <math>~E(\mu)</math> | †<math>K(\mu)~</math> | <math>~E(\mu)</math> | |

| 0.34202014 | 1.62002589 | 1.52379921 | 1.6198 | 1.5239 | 1.6200263 | 1.5237989 |

| 0.57357644 | 1.73124518 | 1.43229097 | 1.7239 | 1.4336 | 1.73124518 | 1.43230 |

| 0.76604444 | 1.93558110 | 1.30553909 | 1.8773 | 1.3150 | 1.93558109 | 1.3061 |

| 0.90630779 | 2.30878680 | 1.16382796 | 2.042 | 1.199 | 2.308784 | 1.1700 |

| 0.98480775 | 3.15338525 | 1.04011440 | 2.16 | 1.12 | 3.150 | 1.069 |

|

†We actually used the "descending Landen transformation" to evaluate <math>~K(\mu)</math> through <math>~\mathcal{O}(\mu^{10})</math>. |

||||||

For <math>~c=1</math> and a specification of the ratio, <math>~a/c</math>, take the following steps to map out an equipotential curve that has <math>~V_2 = V_0</math>:

- Choose a value of <math>~R \ge a</math>

- Guess a value of <math>~(c-R) \le R_1 \le (c+R) ~~~\Rightarrow ~~~ \varpi = (R_1^2 - R^2)/(4c)</math> and, <math>~z = \pm \sqrt{ R_1^2 - (c+\varpi)^2}</math>

- Set <math>~ \cos\psi = (R_1^2 + R^2 - 4c^2)/(2RR_1)</math>

- Evaluate the function, <math>~V_2</math>

- If <math>~V_2 \ne V_0</math> to the desired accuracy, loop back up and guess another value of <math>~R_1</math>

- If <math>~V_2 = V_0</math> to the desired accuracy, save the coordinate location, <math>~(\varpi,z)</math>, and loop back up to pick another value of <math>~R</math>

|

Tabulated Data

As the data in the following table documents, we have been able to construct equipotential contours that agree with Dyson, not only qualitatively, but quantitatively. For example:

- The dark green contour has been designed to touch the surface of the torus precisely where its outermost edge cuts through the equatorial plane <math>~(\varpi,z) = (1.4,0)</math>. This means that <math>~R = 0.4</math> and <math>~R_1 = 2.4</math>. (These four coordinate values are highlighted in pink in the second major column of the table.) When we plugged these values of <math>~R</math> and <math>~R_1</math> into Dyson's expression for <math>~V_2</math>, we determined that the value of the potential at this point on the torus surface is 0.8551 — see the yellow-highlighted heading of the second major table column. Compare this to the value of 0.855 that Dyson has printed just below the Figure 3 x-axis where a fiducial identifies the coordinate, <math>~\varpi = 1.4</math>. As has been catalogued at the bottom of table column #2, we have found that this dark-green contour touches the vertical axis at the coordinate location, <math>~(\varpi,z) = (0,0.572)</math>, for which, <math>~R_1 = R = 1.1518</math>.

- By design — see the coordinate values highlighted in pink in table column #1 — our outermost (pink) contour touches the equatorial plane at <math>~(\varpi,z) = (1.5,0) ~\Rightarrow ~ (R,R_1) = (0.5,2.5)</math>. When we plugged these values of <math>~R</math> and <math>~R_1</math> into Dyson's expression for <math>~V_2</math>, we determined that the value of the potential at this point outside the torus is 0.7737 — see the yellow-highlighted heading of table column #1. Compare this to the value of 0.777 that Dyson has printed just below the Figure 3 x-axis where a fiducial identifies the coordinate, <math>~\varpi = 1.5</math>. As has been catalogued at the bottom of table column #1, we have found that this pink contour touches the vertical axis at the coordinate location, <math>~(\varpi,z) = (0,0.794)</math>, for which, <math>~R_1 = R = 1.2766</math>.

- Similarly, we have constructed contours that intersect the equatorial plane at the fiducials marking <math>~\varpi = 0.0</math> (red curve & table column #5), <math>~\varpi = 0.2</math> (light-green curve & table column #6), and <math>~\varpi = 0.4</math> (light-blue curve & table column #7). According to our calculations, they correspond, respectively, to values of the potential, <math>~V_2 = 0.9800</math> (Dyson's corresponding fiducial label is 0.980), <math>~V_2 = 0.9896</math> (Dyson's corresponding fiducial label is 0.990), and <math>~V_2 = 1.0212</math> (Dyson's corresponding fiducial label is 1.021).

- Finally, we constructed two contours (blue and orange) by initially specifying the value of the potential, rather than specifying the coordinate values <math>~(R,R_1)</math>. We used the values of the potential that Dyson associated with the fiducials along the vertical axis at <math>~(\varpi,z) = (0.0,0.4)</math> and at <math>~(\varpi,z) = (0.0,0.2)</math>: Respectively, <math>~V_2 = 0.912</math> — blue contour detailed in our table column #3 — and <math>~V_2 = 0.961</math>— orange contour detailed in our table column #4. We determined that these two contour curves intersected the vertical axis at, respectively, <math>~(\varpi,z) = (0.0, 0.402)</math> and <math>~(\varpi,z) = (0.0, 0.204)</math>, that is, at coordinate locations that were nearly identical to the locations labeled by Dyson.

|

Coordinates of Points that Trace Seven Different Equipotential Contours External to the Anchor Ring With <math>~c/a = 5/2</math> |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Column #1 | Column #2 | Column #3 | Column #4 | Column #5 | Column #6 | Column #7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Interior Potential

In equation (9) on p. 1050 of his "Part II", Dyson (1893b) presents the following power-series expression for the gravitational potential at points inside the torus:

|

<math>~V</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ 2\pi a^2 \biggl\{ L + \frac{1}{2}\biggl( 1 - \frac{R^2}{a^2}\biggr) + \frac{a}{c}\biggl[ \frac{(L-1)}{2}\biggl(\frac{R}{a}\biggr) - \frac{R^3}{8a^3} \biggr]\cos\chi </math> |

|

|

|

<math>~+~ \frac{a^2}{c^2}\biggl[ - ~\frac{(L - \tfrac{1}{4})}{16} ~+~ \frac{(L-1)}{8} \biggl(\frac{R^2}{a^2} \biggr) ~-~ \frac{3}{64} \biggl( \frac{R^4}{a^4}\biggr) ~+~ \frac{3(L-\tfrac{5}{4})}{16} \biggl(\frac{R^2}{a^2}\biggr) \cos 2\chi ~-~\frac{5}{96} \biggl( \frac{R^4}{a^4}\biggr) \cos 2\chi \biggr] ~+~ \cdots \biggr\} </math> |

where,

|

<math>~L</math> |

<math>~\equiv</math> |

<math>~\ln\biggl(\frac{8c}{a}\biggr) \, .</math> |

Note that, for the example illustrated above, <math>~a/c = 2/5</math> and, hence, <math>~L = \ln(20) = 2.99573</math>. Therefore, at any point on the surface of this example torus,

|

<math>~\frac{V}{2\pi a^2}</math> |

<math>~\approx</math> |

<math>~ \ln(20) + \frac{2}{5}\biggl[ \frac{\ln(20)-1}{2} - \frac{1}{8} \biggr]\cos\chi </math> |

|

|

|

<math>~+~ \frac{2^2}{5^2}\biggl[ - ~\frac{4\ln(20) - 1}{64} ~+~ \frac{\ln(20)-1}{8} ~-~ \frac{3}{64} ~+~ \frac{12\ln(20)-15}{64} \cos 2\chi ~-~\frac{10}{3\cdot 64} \cos 2\chi \biggr] </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ \ln(20) + \frac{2}{40}\biggl[ 4\ln(20)- 5 \biggr]\cos\chi ~+~ \frac{2^2}{2^6\cdot 5^2}\biggl\{ - ~[4\ln(20) - 1] ~+~ [8\ln(20)-8] ~-~ 3 ~+~ [12\ln(20)-15] \cos 2\chi ~-~\biggl(\frac{10}{3} \biggr) \cos 2\chi \biggr\} </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ \ln(20) + \frac{1}{20}\biggl[ 4\ln(20)- 5 \biggr]\cos\chi ~+~ \frac{1}{2^4\cdot 5^2}\biggl\{ 4\ln(20)-10 ~+~ \frac{1}{3}\biggl[ 36\ln(20)-55 \biggr] \cos 2\chi \biggr\} </math> |

Red Contour

Let's construct an equipotential contour that extends the red contour into the interior region. Let's begin by evaluating Dyson's interior potential expression at the coordinate location where the red contour touches the surface of the torus. According to Column #5, this point on the surface has coordinates, <math>~(\varpi,z) = (0.867, 0.377)</math>; or, equivalently, <math>~R = a = 0.4</math> and,

|

<math>~\cos\chi</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ \frac{1-\varpi}{R} = 0.3325 </math> |

|

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~ \chi</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ \cos^{-1}(0.3325) = 1.2318 \, . </math> |

Hence, for this specific point on the torus surface, we find,

|

<math>~\frac{V}{2\pi a^2}</math> |

<math>~\approx</math> |

<math>~ 3 + \biggl[\frac{7}{20}\biggr]\cos\chi ~+~ \frac{1}{2^4\cdot 5^2}\biggl\{ 2 ~+~ \biggl[ \frac{53}{3} \biggr] \cos 2\chi \biggr\} = 3.0870 \, . </math> |

| Contour Column # |

<math>~V_2</math> (external) | Surface <math>~\varpi</math> | <math>~\chi</math> (radians) |

|---|---|---|---|

| red (5) | 0.9800 | 0.867 | 1.2318 |

| light green (6) | 0.9800 | 0.838 | 1.1538 |

See Also

- T. Fukushima (2016, AJ, 152, article id. 35, 31 pp.) — Zonal Toroidal Harmonic Expansions of External Gravitational Fields for Ring-like Objects

- W.-T. Kim & S. Moon (2016, ApJ, 829, article id. 45, 22 pp.) — Equilibrium Sequences and Gravitational Instability of Rotating Isothermal Rings

- E. Y. Bannikova, V. G. Vakulik & V. M. Shulga (2011, MNRAS, 411, 557 - 564) — Gravitational Potential of a Homogeneous Circular Torus: a New Approach

- D. Petroff & S. Horatschek (2008, MNRAS, 389,156 - 172) — Uniformly Rotating Homogeneous and Polytropic Rings in Newtonian Gravity

|

The following quotes have been taken from Petroff & Horatschek (2008):

§1: "The problem of the self-gravitating ring captured the interest of such renowned scientists as Kowalewsky (1885), Poincaré (1885a,b,c) and Dyson (1892, 1893). Each of them tackled the problem of an axially symmetric, homogeneous ring in equilibrium by expanding it about the thin ring limit. In particular, Dyson provided a solution to fourth order in the parameter <math>~\sigma = a/b</math>, where <math>~a = r_t</math> provides a measure for the radius of the cross-section of the ring and <math>~b = \varpi_t</math> the distance of the cross-section's centre of mass from the axis of rotation."

§7: "In their work on homogeneous rings, Poincaré and Kowalewsky, whose results disagreed to first order, both had made mistakes as Dyson has shown. His result to fourth order is also erroneous as we point out in Appendix B." |

- P. H. Chavanis (2006, International Journal of Modern Physics B, 20, 3113 - 3198) — Phase Transitions in Self-Gravitating Systems

- M. Ansorg, A. Kleinwächter & R. Meinel (2003, MNRAS, 339, 515) — Uniformly Rotating Axisymmetric Fluid Configurations Bifurcating from Highly Flattened Maclaurin Spheroids

- M. Lombardi & G. Bertin (2001, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 375, 1091 - 1099) — Boyle's Law and Gravitational Instability

- W. Kley (1996, MNRAS, 282, 234) — Maclurin Discs and Bifurcations to Rings

- J. W. Woodward, J. E. Tohline, & I. Hachisu (1994, ApJ, 420, 247 - 267) — The Stability of Thick, Self-Gravitating Disks in Protostellar Systems

- I. Bonnell & P. Bastien (1991, ApJ, 374, 610 - 622) — The Collapse of Cylindrical Isothermal and Polytropic Clouds with Rotation

- J. E. Tohline & I. Hachisu (1990, ApJ, 361, 394 - 407) — The Breakup of Self-Gravitating Rings, Tori, and Thick Accretion Disks

- F. Schmitz (1988, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 200, 127 - 134) — Equilibrium Structures of Differentially Rotating Self-Gravitating Gases

- P. Veugelen (1985, Astrophysics & Space Science, 109, 45 - 55) — Equilibrium Models of Differentially Rotating Polytropic Cylinders

- M. A. Abramowicz, A. Curir, A. Schwarzenberg-Czerny, & R. E. Wilson (1984, MNRAS, 208, 279 - 291) — Self-Gravity and the Global Structure of Accretion Discs

- P. Bastien (1983, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 119, 109 - 116) — Gravitational Collapse and Fragmentation of Isothermal, Non-Rotating, Cylindrical Clouds

- Y. Eriguchi & D. Sugimoto (1981, Progress of Theoretical Physics, 65, 1870 - 1875) — Another Equilibrium Sequence of Self-Gravitating and Rotating Incompressible Fluid

- J. E. Tohline (1980, ApJ, 236, 160 - 171) — Ring Formation in Rotating Protostellar Clouds

- T. Fukushima, Y. Eriguchi, D. Sugimoto, & G. S. Bisnovatyi-Kogan (1980, Progress of Theoretical Physics, 63, 1957 - 1970) — Concave Hamburger Equilibrium of Rotating Bodies

- J. Katz & D. Lynden-Bell (1978, MNRAS, 184, 709 - 712) — The Gravothermal Instability in Two Dimensions

- P. S. Marcus, W. H. Press, & S. A. Teukolsky (1977, ApJ, 214, 584- 597) — Stablest Shapes for an Axisymmetric Body of Gravitating, Incompressible Fluid (includes torus with non-uniform rotation)

- Shortly after their equation (3.2), Marcus, Press & Teukolsky make the following statement: "… we know that an equilibrium incompressible configuration must rotate uniformly on cylinders (the famous "Poincaré-Wavre" theorem, cf. Tassoul 1977, &Sect;4.3) …"

- C. J. Hansen, M. L. Aizenman, & R. L. Ross (1976, ApJ, 207, 736 - 744) — The Equilibrium and Stability of Uniformly Rotating, Isothermal Gas Cylinders

- C.-Y. Wong (1974, ApJ, 190, 675 - 694) — Toroidal Figures of Equilibrium

- C.-Y. Wong (1973, Annals of Physics, 77, 279 - 353) — Toroidal and Spherical Bubble Nuclei

- J. Ostriker (1964, ApJ, 140, 1056) — The Equilibrium of Polytropic and Isothermal Cylinders

- J. Ostriker (1964, ApJ, 140, 1067) — The Equilibrium of Self-Gravitating Rings

- J. Ostriker (1964, ApJ, 140, 1529) — On the Oscillations and the Stability of a Homogeneous Compressible Cylinder

- J. Ostriker (1965, ApJ Supplements, 11, 167) — Cylindrical Emden and Associated Functions

- Gunnar Randers (1942, ApJ, 95, 88) — The Equilibrium and Stability of Ring-Shaped 'barred SPIRALS'.

- William Duncan MacMillan (1958), The Theory of the Potential, New York: Dover Publications

- Oliver Dimon Kellogg (1929), Foundations of Potential Theory, Berlin: Verlag Von Julius Springer

- Lord Rayleigh (1917, Proc. Royal Society of London. Series A, 93, 148-154) — On the Dynamics of Revolving Fluids

- F. W. Dyson (1893, Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society London. A., 184, 1041 - 1106) — The Potential of an Anchor Ring. Part II.

- In this paper, Dyson derives the gravitational potential inside the ring mass distribution

- F. W. Dyson (1893, Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society London. A., 184, 43 - 95) — The Potential of an Anchor Ring. Part I.

- In this paper, Dyson derives the gravitational potential exterior to the ring mass distribution

- S. Kowalewsky (1885, Astronomische Nachrichten, 111, 37) — Zusätze und Bemerkungen zu Laplace's Untersuchung über die Gestalt der Saturnsringe

- Poincaré (1885a, C. R. Acad. Sci., 100, 346), (1885b, Bull. Astr., 2, 109), (1885c, Bull. Astr. 2, 405). — references copied from paper by Wong (1974)

|

|---|

|

© 2014 - 2021 by Joel E. Tohline |