Difference between revisions of "User:Tohline/Apps/ImamuraHadleyCollaboration"

(→Radial Modes in Homogeneous Spheres: Inserted brief discussion of radial modes and instability) |

|||

| Line 231: | Line 231: | ||

When these radial modes of oscillation are discussed in the astrophysics literature, the conditions that give rise to a dynamical instability are often emphasized. Specifically, each mode becomes unstable when <math>~\sigma^2</math> becomes negative, which translates into a value of <math>~\gamma < \gamma_\mathrm{crit}(m)</math>. Here we want to emphasize that all of these radial eigenmodes ''exist'' even when the configuration is dynamically stable. | When these radial modes of oscillation are discussed in the astrophysics literature, the conditions that give rise to a dynamical instability are often emphasized. Specifically, each mode becomes unstable when <math>~\sigma^2</math> becomes negative, which translates into a value of <math>~\gamma < \gamma_\mathrm{crit}(m)</math>. Here we want to emphasize that all of these radial eigenmodes ''exist'' even when the configuration is dynamically stable. | ||

===Singular Sturm-Liouville Problem=== | |||

[[User:Tohline/Apps/Blaes85SlimLimit#Singular_Sturm-Liouville_Problem|As we have discussed in a separate chapter]], there is a class of eigenvalue problems in the mathematical physics literature that is of the "Singular Sturm-Liouville" type. These problems are governed by a one-dimensional, 2<sup>nd</sup>-order ODE of the form, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~-(1-x)^{-\alpha}(1+x)^{-\beta} \cdot \frac{d}{dx} \biggl[ (1-x)^{\alpha+1}(1+x)^{\beta+1} \cdot \frac{d\Upsilon(x)}{dx} \biggr]</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~ | |||

\lambda \Upsilon(x) \, , | |||

</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

where the pair of exponent values, <math>~(\alpha, \beta) </math>, is set by the specific physical problem, while the eigenfunction, <math>~\Upsilon(x)</math>, and associated eigenfrequency, <math>~\lambda</math>, are to be determined. For any choice of the pair of exponents, there is an infinite number <math>~(j = 0 \rightarrow \infty)</math> of ''analytically known'' eigenvectors that satisfy this governing ODE; they are referred to as ''Jacobi Polynomials.'' Specifically, the j<sup>th</sup> eigenfunction is, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\Upsilon_j(x) = J_j^{\alpha,\beta}(x)</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~\equiv</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~(1-x)^{-\alpha}(1+x)^{-\beta} \biggl\{ | |||

\frac{(-1)^j}{2^j j!} \cdot \frac{d^j}{dx^j}\biggl[ (1-x)^{j+\alpha}(1+x)^{j+\beta} \biggr] | |||

\biggr\} \, ;</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

and the corresponding j<sup>th</sup> eigenvalue is, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\lambda_j^{\alpha,\beta}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~j(j+\alpha+\beta + 1) \, .</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

Table 3 presents the first three eigenfunctions (j = 0, 1, 2), along with each corresponding eigenfrequency. | |||

<div align="center" id="Table3"> | |||

<table align="center" border="1" cellpadding="5"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<th align="center" colspan="4"><font size="+1">Table 3: Example Eigenvector Solutions to the Singular Sturm-Liouville Problem</font></th> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~j</math></td> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~J_j^{\alpha,\beta}(x)</math></td> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~\lambda_j^{\alpha,\beta}</math></td> | |||

<td align="center" rowspan="5">[[File:JacobiPolynomialsAS.png|200px|Jacobi Polynomials]]</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~0</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~1</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~0</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~1</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~\tfrac{1}{2}(\alpha+\beta+2)x + \tfrac{1}{2}(\alpha-\beta)</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~(\alpha+\beta+2)</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~2</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~ | |||

\tfrac{1}{8}(12+7\alpha + \alpha^2 + 7\beta+\beta^2+ 2\alpha\beta ) x^2 | |||

+ \tfrac{1}{4}(3\alpha + \alpha^2 - 3\beta-\beta^2) x | |||

+ \tfrac{1}{8}(-4 - \alpha + \alpha^2-\beta + \beta^2 - 2\alpha\beta) | |||

</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~2(\alpha+\beta+3)</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="left" colspan="3">See also, eqs. (35)-(37) of [http://mathworld.wolfram.com/JacobiPolynomial.html Wolfram MathWorld]; and the section from [http://people.math.sfu.ca/~cbm/aands/page_773.htm Abramowitz and Stegun's (1984)] ''Handbook of Mathematical Functions,'' from which the illustration on the right was extracted. | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

=See Also= | =See Also= | ||

Revision as of 23:58, 8 May 2016

Characteristics of Unstable Eigenvectors in Self-Gravitating Tori

|

|---|

| | Tiled Menu | Tables of Content | Banner Video | Tohline Home Page | |

In what follows, we will draw heavily from three publications: (1) J. E. Tohline & I. Hachisu (1990, ApJ, 361, 394-407) — hereafter, TH90 — (2) J. W. Woodward, J. E. Tohline, & I. Hachisu (1994, ApJ, 420, 247-267) — hereafter, WTH94 — and (3) K. Hadley & J. N. Imamura (2011, Astrophysics and Space Science, 334, 1) — hereafter, HI11.

Background

Imamura & Hadley Collaboration

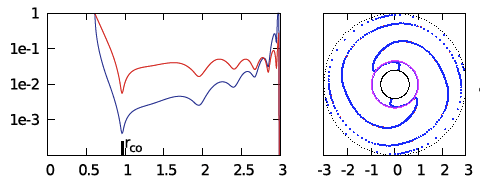

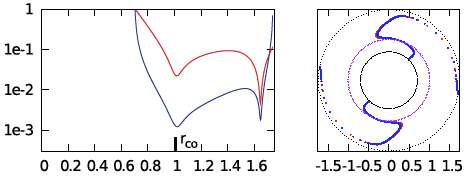

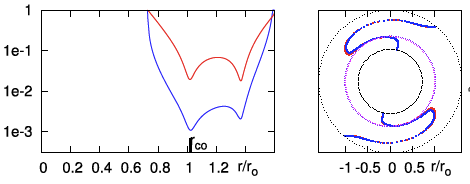

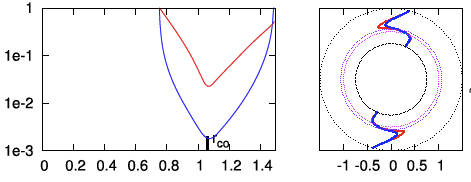

Based especially on the analysis provided in Paper I and Paper II of the Imamura & Hadley collaboration, the eigenvectors that have drawn our attention thus far can be categorized as J-modes (as discussed, for example, in §3.2.1, Table 1 & Figure 2 of Paper II) or I-modes. Our initial attempts to construct fits to these eigenvectors empirically have been described in an separate chapter. We begin, here, a more quantitative analysis of the structure of these unstable eigenvectors by borrowing from a subsection of that chapter a table of equilibrium parameter values for the typical P- and E-mode models described in Table 2 of Paper II.

| Table 1: P- and E-mode Model Parameters Highlighted in Paper II K. Z. Hadley, P. Fernandez, J. N. Imamura, E. Keever, R. Tumblin, & W. Dumas (2014, Astrophysics and Space Science, 353, 191-222) | |||||||||

| Extracted from Table 2 or Table 4 of Paper II | Deduced Here | Extracted from Fig. 3 or Fig. 4 of Paper II | |||||||

| Name | <math>~M_*/M_d</math> | <math>~(n, q)</math>† | <math>~R_-/R_+</math> | <math>~r_\mathrm{outer} \equiv \frac{R_+}{R_\mathrm{max}}</math> | <math>~R_\mathrm{max}</math> | <math>~R_+</math> | <math>~\epsilon \equiv \frac{R_\mathrm{max}-R_-}{R_\mathrm{max}}</math> | <math>~r_- \equiv \frac{R_-}{R_\mathrm{max}}</math> | Eigenfunction |

| E1 | <math>~100</math> | <math>~(\tfrac{3}{2}, 2)</math> | <math>~0.101</math> | <math>~5.52</math> | <math>~0.00613</math> | <math>~0.0338</math> | <math>~0.442</math> | <math>~0.558</math> | |

| E2 | <math>~100</math> | <math>~(\tfrac{3}{2}, 2)</math> | <math>~0.202</math> | <math>~2.99</math> | <math>~0.0229</math> | <math>~0.0685</math> | <math>~0396</math> | <math>~0.604</math> |  |

| E3 | <math>~100</math> | <math>~(\tfrac{3}{2}, 2)</math> | <math>~0.402</math> | <math>~1.74</math> | <math>~0.159</math> | <math>~0.277</math> | <math>~0.301</math> | <math>~0.699</math> |  |

| P1 | <math>~100</math> | <math>~(\tfrac{3}{2}, 2)</math> | <math>~0.452</math> | <math>~1.60</math> | <math>~0.254</math> | <math>~0.406</math> | <math>~0.277</math> | <math>~0.723</math> |  |

| P2 | <math>~100</math> | <math>~(\tfrac{3}{2}, 2)</math> | <math>~0.500</math> | <math>~1.49</math> | <math>~0.403</math> | <math>~0.600</math> | <math>~0.255</math> | <math>~0.745</math> |  |

| P3 | <math>~100</math> | <math>~(\tfrac{3}{2}, 2)</math> | <math>~0.600</math> | <math>~1.33</math> | <math>~1.09</math> | <math>~1.450</math> | <math>~0.202</math> | <math>~0.798</math> | |

| P4 | <math>~100</math> | <math>~(\tfrac{3}{2}, 2)</math> | <math>~0.700</math> | <math>~1.21</math> | <math>~3.37</math> | <math>~4.078</math> | <math>~0.153</math> | <math>~0.847</math> | |

| †In all three papers from the Imamura & Hadley collaboration, <math>~q = 2</math> means, "uniform specific angular momentum." | |||||||||

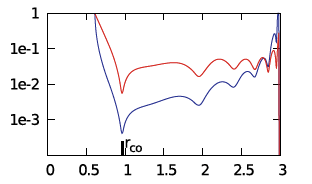

We ask, first, "Can we understand why the radial eigenfunction of, for example, model E2 — re-displayed here, on the right — exhibits a series of sharp dips whose spacing gets progressively smaller and smaller as the outer edge of the torus is approached?"

Radial Modes in Homogeneous Spheres

Before attempting to analyze natural modes of oscillation in a polytropic torus, it is useful to review what is known about radial oscillations in the geometrically simpler, uniform-density sphere. As we have reviewed in a separate chapter, Sterne (1937) was the first to recognize that the set of eigenvectors that describe radial modes of oscillation in a homogeneous, self-gravitating sphere can be determined analytically. In the present context, it is advantageous for us to pull Sterne's solution from a discussion of the same problem presented by Rosseland (1964). As we have summarized in a separate chapter, the relevant eigenvalue problem is defined by the following one-dimensional, 2nd-order ODE:

|

<math>~ ( 1-\chi_0^2 ) \frac{\partial^2 \xi}{\partial \chi_0^2} + \frac{2}{\chi_0}\biggl[ 1 - 2\chi_0^2 \biggr] \frac{\partial \xi}{\partial \chi_0} + \biggl(4 - \frac{2}{\chi_0^2} \biggr) \xi</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ - \mathfrak{F} \xi \, , </math> |

where, it is understood that the expression for the (spatially and temporally varying) radial location of each spherical shell is,

<math>~r(r_0,t) = r_0 + \delta r(r_0)e^{i\sigma t} \, ,</math>

and in the present context we are adopting the variable notation,

|

<math>~\chi_0</math> |

<math>~\equiv</math> |

<math>~\frac{r_0}{R} \, ,</math> |

|

<math>~\xi</math> |

<math>~\equiv</math> |

<math>~\frac{\delta r}{R} \, ,</math> |

and <math>~R</math> is the initial (unperturbed) radius of the sphere. Here, the eigenvalue is related to the physical properties of the homogeneous sphere via the relation,

<math>~\mathfrak{F} \equiv \frac{2}{\gamma_\mathrm{g}} \biggl[\biggl(\frac{3\sigma^2}{4\pi G\rho_0}\biggr) + (4 - 3\gamma_\mathrm{g}) \biggr] \, .</math>

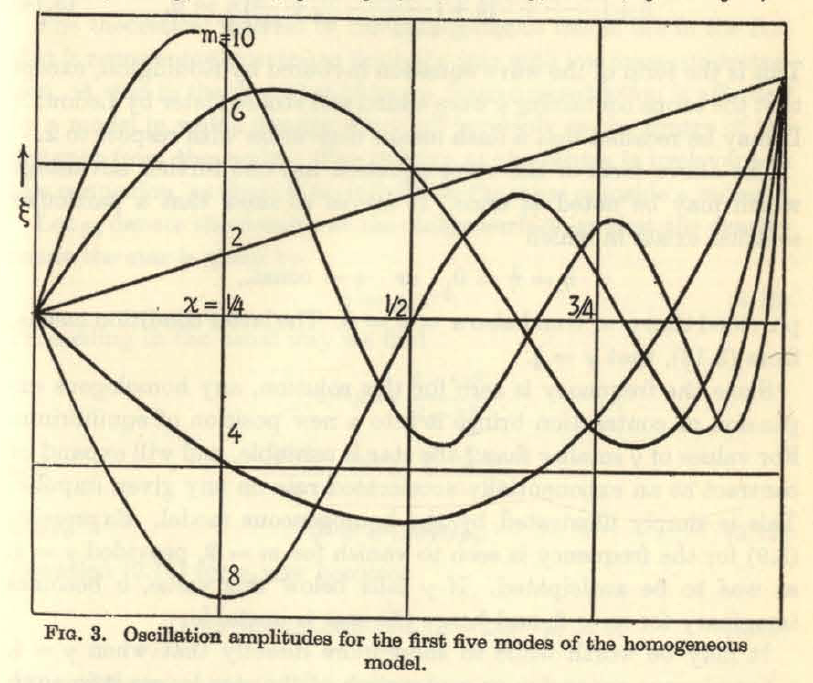

Drawing from Rosseland's (1964) presentation — see his p. 29, and our related discussion — the following table details the eigenvectors (radial eigenfunction and associated eigenfrequency) for the three lowest radial modes (m = 2, 4, 6) that satisfy this wave equation; the figure displayed in the right-most column has been extracted directly from p. 29 of Rosseland and shows the behavior of the lowest five radial modes (m = 2, 4, 6, 8, 10), as labeled.

|

Table 2

Rosseland's (1964) Eigenfunctions for Homogeneous Sphere

Figure in the right-most column extracted from p. 29 of Rosseland (1964)

"The Pulsation Theory of Variable Stars" (New York: Dover Publications, Inc.) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | Eigenfunction | Square of Eigenfrequency:<math>~3\sigma^2/(4\pi G\rho)</math> | |

| <math>~m</math> | As Published | <math>~\frac{m}{2}(m+1)\gamma - 4</math> | |

| <math>~2</math> | <math>~\xi = -2\chi_0</math> | <math>~3\gamma - 4</math> | |

| <math>~4</math> | <math>~\xi = -\frac{20}{3}\chi_0 + \frac{28}{3}\chi_0^3</math> | <math>~10\gamma-4</math> | |

| <math>~6</math> | <math>~\xi = -14\chi_0 + \frac{252}{5} \chi_0^3 - \frac{198}{5} \chi_0^5</math> | <math>~21\gamma-4</math> | |

We should point out that, except for the lowest (m = 2) mode, each of the radial eigenfunctions crosses zero at least once at some location(s) that resides between the center <math>~(\chi_0=0)</math> of and the surface <math>~(\chi_0 = 1)</math> of the sphere. More specifically, the number of such radial "nodes" is <math>~(m-2)/2</math>. The locations of these nodes is apparent from even a casual inspection of the figure presented in the right-most column of Table 2.

When these radial modes of oscillation are discussed in the astrophysics literature, the conditions that give rise to a dynamical instability are often emphasized. Specifically, each mode becomes unstable when <math>~\sigma^2</math> becomes negative, which translates into a value of <math>~\gamma < \gamma_\mathrm{crit}(m)</math>. Here we want to emphasize that all of these radial eigenmodes exist even when the configuration is dynamically stable.

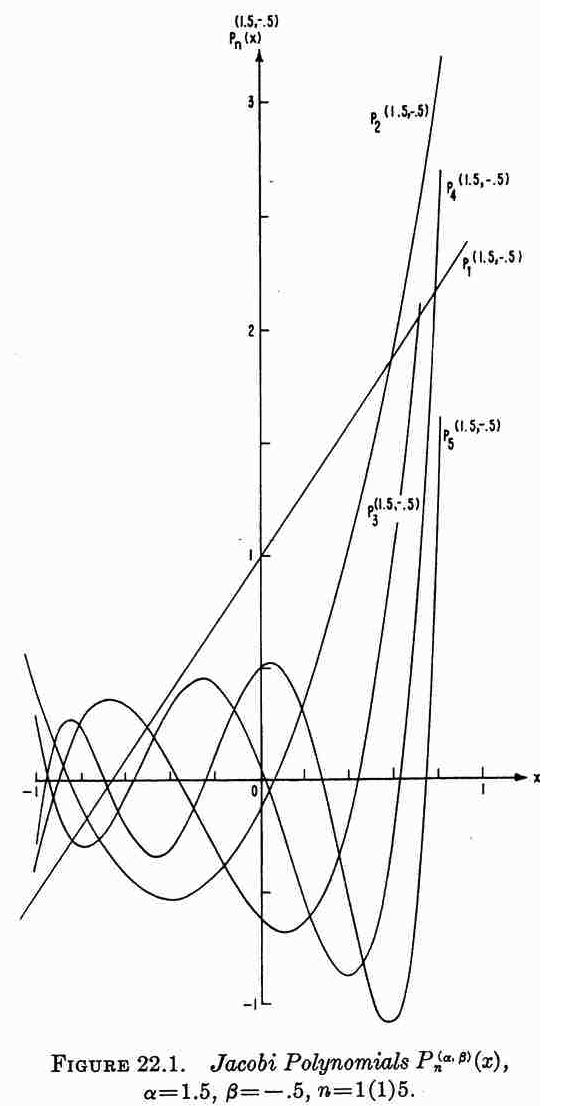

Singular Sturm-Liouville Problem

As we have discussed in a separate chapter, there is a class of eigenvalue problems in the mathematical physics literature that is of the "Singular Sturm-Liouville" type. These problems are governed by a one-dimensional, 2nd-order ODE of the form,

|

<math>~-(1-x)^{-\alpha}(1+x)^{-\beta} \cdot \frac{d}{dx} \biggl[ (1-x)^{\alpha+1}(1+x)^{\beta+1} \cdot \frac{d\Upsilon(x)}{dx} \biggr]</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ \lambda \Upsilon(x) \, , </math> |

where the pair of exponent values, <math>~(\alpha, \beta) </math>, is set by the specific physical problem, while the eigenfunction, <math>~\Upsilon(x)</math>, and associated eigenfrequency, <math>~\lambda</math>, are to be determined. For any choice of the pair of exponents, there is an infinite number <math>~(j = 0 \rightarrow \infty)</math> of analytically known eigenvectors that satisfy this governing ODE; they are referred to as Jacobi Polynomials. Specifically, the jth eigenfunction is,

|

<math>~\Upsilon_j(x) = J_j^{\alpha,\beta}(x)</math> |

<math>~\equiv</math> |

<math>~(1-x)^{-\alpha}(1+x)^{-\beta} \biggl\{ \frac{(-1)^j}{2^j j!} \cdot \frac{d^j}{dx^j}\biggl[ (1-x)^{j+\alpha}(1+x)^{j+\beta} \biggr] \biggr\} \, ;</math> |

and the corresponding jth eigenvalue is,

|

<math>~\lambda_j^{\alpha,\beta}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~j(j+\alpha+\beta + 1) \, .</math> |

Table 3 presents the first three eigenfunctions (j = 0, 1, 2), along with each corresponding eigenfrequency.

| Table 3: Example Eigenvector Solutions to the Singular Sturm-Liouville Problem | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| <math>~j</math> | <math>~J_j^{\alpha,\beta}(x)</math> | <math>~\lambda_j^{\alpha,\beta}</math> |  |

|

<math>~0</math> |

<math>~1</math> |

<math>~0</math> |

|

|

<math>~1</math> |

<math>~\tfrac{1}{2}(\alpha+\beta+2)x + \tfrac{1}{2}(\alpha-\beta)</math> |

<math>~(\alpha+\beta+2)</math> |

|

|

<math>~2</math> |

<math>~ \tfrac{1}{8}(12+7\alpha + \alpha^2 + 7\beta+\beta^2+ 2\alpha\beta ) x^2 + \tfrac{1}{4}(3\alpha + \alpha^2 - 3\beta-\beta^2) x + \tfrac{1}{8}(-4 - \alpha + \alpha^2-\beta + \beta^2 - 2\alpha\beta) </math> |

<math>~2(\alpha+\beta+3)</math> |

|

| See also, eqs. (35)-(37) of Wolfram MathWorld; and the section from Abramowitz and Stegun's (1984) Handbook of Mathematical Functions, from which the illustration on the right was extracted. | |||

See Also

- Imamura & Hadley collaboration:

- Paper I: K. Hadley & J. N. Imamura (2011, Astrophysics and Space Science, 334, 1-26), "Nonaxisymmetric instabilities in self-gravitating disks. I. Toroids" — In this paper, Hadley & Imamura perform linear stability analyses on fully self-gravitating toroids; that is, there is no central point-like stellar object and, hence, <math>~M_*/M_d = 0.0</math>.

- Paper II: K. Z. Hadley, P. Fernandez, J. N. Imamura, E. Keever, R. Tumblin, & W. Dumas (2014, Astrophysics and Space Science, 353, 191-222), "Nonaxisymmetric instabilities in self-gravitating disks. II. Linear and quasi-linear analyses" — In this paper, the Imamura & Hadley collaboration performs "an extensive study of nonaxisymmetric global instabilities in thick, self-gravitating star-disk systems creating a large catalog of star/disk systems … for star masses of <math>~0.0 \le M_*/M_d \le 10^3</math> and inner to outer edge aspect ratios of <math>~0.1 < r_-/r_+ < 0.75</math>."

- Paper III: K. Z. Hadley, W. Dumas, J. N. Imamura, E. Keever, & R. Tumblin (2015, Astrophysics and Space Science, 359, article id. 10, 23 pp.), "Nonaxisymmetric instabilities in self-gravitating disks. III. Angular momentum transport" — In this paper, the Imamura & Hadley collaboration carries out nonlinear simulations of nonaxisymmetric instabilities found in self-gravitating star/disk systems and compares these results with the linear and quasi-linear modeling results presented in Papers I and II.

|

|---|

|

© 2014 - 2021 by Joel E. Tohline |